|

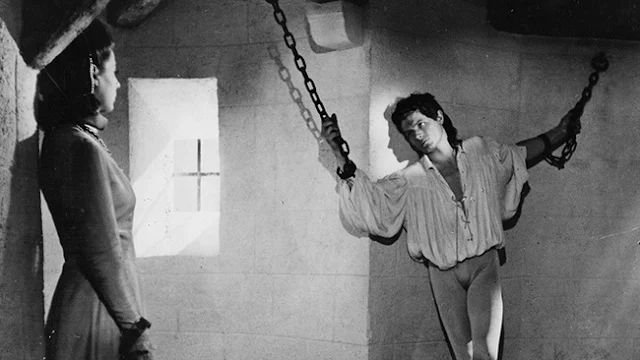

| Melvyn Douglas, Herbert Marshall, and Marlene Dietrich in Angel |

Sir Frederick Barker: Herbert Marshall

Anthony Halton: Melvyn Douglas

Graham: Edward Everett Horton

Wilton: Ernest Cossart

Grand Duchess Anna Dimitrievna: Laura Hope Crews

Mr. Greenwood: Herbert Mundin

Emma: Dennie Moore

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Screenplay: Samson Raphaelson, Guy Bolton, Russell G. Medcraft

Based on a play by Melchior Lengyel

Cinematography: Charles Lang

Art direction: Hans Dreier, Robert Usher

Film editing: William Shea

Costume design: Travis Banton

Music: Friedrich Hollaender

In Ernst Lubitsch's Angel, you can almost feel the Production Code censors breathing hotly down the director's neck, driving some of the oxygen out of the room. What's meant to be a light and airy sophisticated comedy, like for example Lubitsch's pre-Code masterpiece Trouble in Paradise (1932), often feels starchy and coy. The emigrée grand duchess played by Laura Hope Crews is clearly a high-class procuress and her "salon" a very upscale brothel that enables a "fling" by Lady Maria Barker with a curiously naïve Anthony Halton. Their affair never seems to get consummated, although there are the usual narrative jumps when the relationship seems to come to the boiling point. And of course the Code's aversion to divorce and abhorrence of any sign that adulterers might get away with it unpunished means that the film must end with Lady Maria and Sir Frederick happily reconciled. We're used to such evasions in Hollywood movies of the 1930s through the 1950s, but it's a little depressing to see them stifle Lubitsch's usually sublime naughtiness. Sometimes it feels as if Marlene Dietrich is to blame: She never really strikes sparks with either Melvyn Douglas or Herbert Marshall -- certainly not the way Greta Garbo does with Douglas in Ninotchka (1939) or Miriam Hopkins with Marshall in Trouble in Paradise. But lovers of Lubitsch have plenty to enjoy in Angel, chiefly the way the director subverts expectations. When Sir Frederick invites Halton, an old war buddy, to dine with him and his wife, who neither man knows is the "Angel" Halton met in Paris and has been rhapsodizing about ever since, we expect a big explosion, especially when the husband points out his wife's picture to her lover. But just as Halton is about to look at the photograph, Lubitsch cuts. We don't see the awkward encounter between wife and lover we expect when she comes downstairs to meet the guest. Instead, we pick up with them later and realize that both have exerted exceptional self-control at the meeting. And we don't see the three of them at the dinner table; instead, Lubitsch takes us into the kitchen, where the servants are wondering why neither Lady Maria nor Mr. Halton has touched their food. Lubitsch leaves to our imagination scenes that other directors would have milked shamelessly. In another example, at their first encounter Maria and Halton are in a Parisian park at night, and after he proclaims his love for her he spots an old woman selling violets. He goes to buy the flowers, but Lubitsch holds the camera on the old woman, whose expressions tell us what's going on: Maria has chosen the moment to disappear and we hear Halton calling out "Angel!" in his pursuit of her. The flower seller sighs and picks up the dropped bouquet, dusts it off, and puts it back with the other flowers, then turns and walks away. Similarly, Lubitsch doesn't linger on the reconciliation scene between Maria and Frederick: They simply walk out the door, headed for Vienna and what we hope is a revived marriage. In the end, these "Lubitsch touches" aren't quite enough to lift Angel out of the middle tier of the director's films, but they constitute its saving grace notes.