A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, November 30, 2015

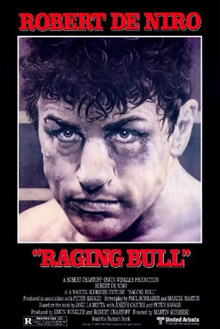

Raging Bull (Martin Scorsese, 1980)

Sunday, November 29, 2015

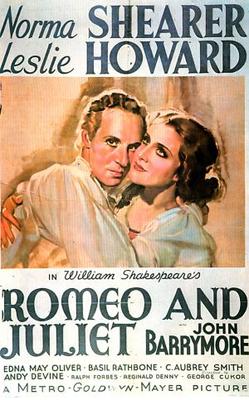

Romeo and Juliet (George Cukor, 1936)

Saturday, November 28, 2015

The Barretts of Wimpole Street (Sidney Franklin, 1934)

Friday, November 27, 2015

Watch on the Rhine (Herman Shumlin, 1943)

The Flowers of St. Francis (Roberto Rossellini, 1950)

Thursday, November 26, 2015

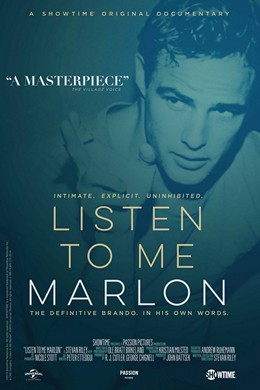

Listen to Me Marlon (Stevan Riley, 2015)

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder, 1959)

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

The Seven Year Itch (Billy Wilder, 1955)

Monday, November 23, 2015

The Night of the Hunter (Charles Laughton, 1955)

Sunday, November 22, 2015

Bombshell (Victor Fleming, 1933)

Saturday, November 21, 2015

Their Own Desire (E. Mason Hopper, 1929)

Friday, November 20, 2015

A Free Soul (Clarence Brown, 1931)

|

| Clark Gable and Norma Shearer in A Free Soul |

Dwight Winthrop: Leslie Howard

Stephen Ashe: Lionel Barrymore

Ace Wilfong: Clark Gable

Eddie: James Gleason

Director: Clarence Brown

Screenplay: John Meehan, Becky Gardiner

Based on a novel by Adela Rogers St. Johns and a play by Willard Mack

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Art director: Cedric Gibbons

Costume design: Adrian

Norma Shearer made the transition to talkies easily: She had a well-placed voice and, when the role called for it, a natural way of handling dialogue. Unfortunately, A Free Soul doesn't call for much in the way of "natural" for Shearer, and it's one of the films that suggest why, of the major female stars of the 1930s (Garbo, Crawford, Loy, Harlow, Stanwyck, Dietrich, Hepburn, Colbert), she is the least remembered. She works hard at her role as the free-spirited daughter of an alcoholic defense attorney, but too often her work is undone by a tendency, perhaps carried over from silent films, to strike mannered poses: typically, hands on hips, shoulders back, chin high. She looks great, however, in the barely-there gowns designed for her by Adrian, which seem to be held in place by will power (or double-sided tape). The plot calls on her to try to dry out her drunken father by wagering that if he can sober up, she'll give up her relationship with the sexy gangster her father managed to save from a murder rap. That gangster is played by Clark Gable, who got fifth billing (after James Gleason!), a sign of his status at the time. Gable had been making movies, usually in bit parts, since 1923, but this was the film that catapulted him, at age 30, into stardom. He still stands out in the movie as a natural, unaffected presence amid the mannered Shearer, hammy Lionel Barrymore, and pasty-looking Leslie Howard. It doesn't even hurt Gable that he's cast as a heel named Ace Wilfong, which brings to mind the insurance salesman in It's a Gift (Norman Z. McLeod, 1934) who annoys W.C. Fields with his search for Carl LaFong, "Capital L, small a, capital F, small o, small n, small g. LaFong. Carl LaFong." The improbable story comes from a novel by Adela Rogers St. Johns that had been adapted into a play by Willard Mack. (Incidentally, the play had been directed on Broadway in 1928 by George Cukor and starred Melvyn Douglas as Ace Wilfong.) Barrymore won the best actor Oscar on the strength of the courtroom speech he gives at the film's end. Barrymore claimed that he did it in one take with the help of multiple cameras, but the logistics of lighting for that many cameras makes his story hard to credit.

The Blackbird (Tod Browning, 1926)

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982)

Rick Deckard: Harrison Ford

Roy Batty: Rutger Hauer

Rachael: Sean Young

Gaff: Edward James Olmos

Bryant: M. Emmet Walsh

Pris: Daryl Hannah

J.F. Sebastian: William Sanderson

Zhora: Joanna Cassidy

Director: Ridley Scott

Screenplay: Hampton Fancher, David Webb Peoples

Based on a novel by Philip K. Dick

Cinematography: Jordan Cronenweth

Production design: Laurence G. Paull

Film editing: Marsha Nakashima, Terry Rawlings

Music: Vangelis

I had forgotten that Blade Runner, with its flying cars, ads for Atari and Pan Am, and rainy Los Angeles, was set in the year 2019, which unless things change radically in the next four years puts it on a par with 1984 (Michael Anderson, 1956) and 2001 (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) for missed prognostications. Yet despite this, and even more despite the great advances in special effects technology, this 33-year-old movie hardly feels dated. That's because it isn't over-infatuated with the technological whiz-bang of so many sci-fi films, especially since the advances in CGI. Its effects, supervised by the great Douglas Trumbull, have the solidity and tactility so often missing in CGI work, because they're very much in service of the vision of production designer Laurence G. Paull, art director David L. Snyder, and especially "visual futurist" Syd Mead. But more especially because they're in service of the humanity whose very questionable nature is the point of Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples's adaptation of the Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It also helps that the film has a terrific cast. Harrison Ford can't help bringing a bit of Han Solo and Indiana Jones to every movie, but it's entirely appropriate here -- one time when a star image doesn't fight the script. Rutger Hauer makes Roy Batty's death scene memorable, and even Sean Young, a problematic actress at best, comes off well. (I think it's because when we first see her, she's dressed and coiffed like a drag-queen Joan Crawford, so that when she literally lets her hair down she takes on a softness we're not accustomed to from her.) And then there's Edward James Olmos as the enigmatic origamist Gaff, Daryl Hannah, William Sanderson, and especially Joanna Cassidy, who manages to achieve poignancy even wearing a transparent plastic raincoat. I only wish that HBO would scrap its print of the "voice-over" version of the film, with Ford's sporadic narrative and the happy ending demanded by Warner Bros., and show director Scott's 2007 "Final Cut" version instead.

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Norma Rae (Martin Ritt, 1979)

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

Once (John Carney, 2006)

Monday, November 16, 2015

Bernie (Richard Linklater, 2011)

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Two Norma Shearer Silent Films

|

| Norma Shearer meets Norma Shearer in Lady of the Night |

Molly Helmer/Florence Banning: Norma Shearer

David Page: Malcolm McGregor

Miss Carr: Dale Fuller

"Chunky" Dunn: George K. Arthur

Judge Banning: Fred Esmelton

Chris Helmer: Lew Harvey

Director: Monta Bell

Screenplay: Alice D.G. Miller

Based on a story by Adela Rogers St. Johns

Cinematography: André Barlatier

|

| Norma Shearer and Johnny Mack Brown in A Lady of Chance |

Dolly Morgan: Norma Shearer

Steve Crandall: Johnny Mack Brown

Bradley: Lowell Sherman

Gwen: Gwen Lee

Mrs. Crandall: Eugenie Besserer

Director: Robert Z. Leonard

Screenplay: Edmund Goulding, Andrew Percival Younger, Ralph Spence

Based on a story by Leroy Scott

Cinematography: J. Peverell Marley, William H. Daniels

Saturday, November 14, 2015

Fists in the Pocket (Marco Bellocchio, 1965)

|

Friday, November 13, 2015

The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928)

|

| John Sims, age 12 (Johnny Downs), learns of his father's death. |

|

| A skyscraper echoes the stairwell scene in The Crowd. |

|

| The insurance office in The Crowd. |

Thursday, November 12, 2015

Away From Her (Sarah Polley, 2006)

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

An Angel at My Table (Jane Campion, 1990)

|

| Kerry Fox in An Angel at My Table |

Janet as a child: Karen Fergusson

Janet as a teenager: Alexia Keogh

Mother: Iris Churn

Father: Kevin J. Wilson

Myrtle: Melina Bernecker

Isabel: Glynis Angell

Leslie: Natasha Gray

Miss Botting: Brenda Kendall

Frank Sargeson: Martyn Sanderson

Director: Jane Campion

Screenplay: Laura Jones

Based on books by Janet Frame

Cinematography: Stuart Dryburgh

Production design: Grant Major

Costume design: Glenys Jackson

Music: Don McGlashan

Three years before The Piano (1993) earned her critical acclaim and an Oscar for screenwriting as well as a nomination for directing, Campion made this film, originally as a TV miniseries. It's an account of the life of New Zealand author Janet Frame, told in three segments. Writers' biopics are difficult to bring off, in large part because writers' lives are usually less interesting than the things they write. Their chief function is typically to give us insight into the personal experiences that shaped their art, which in Frame's case included growing up in a working-class family in rural New Zealand, having a mental breakdown while she was at teachers' college, and being misdiagnosed as schizophrenic and institutionalized for eight years at an antiquated mental asylum where she was treated with electroshock therapy. But during her stay at the hospital she wrote a series of short stories that were collected and published, receiving acclaim that eventually resulted in her release. Campion's film is based on three volumes of autobiography by Frame. I have to admit that I've not read any of Frame's books or stories, so I'm not qualified to judge whether the film adds substance to either the autobiography or the fiction, but the screenplay by Laura Jones and the performance by Kerry Fox as the adult Janet Frame (she is played by Alexia Keogh as a teenager and Karen Fergusson as a child) are compelling enough in themselves. I also admit that I had trouble understanding the New Zealand accents, so I lost out on some of the dialogue.

Tuesday, November 10, 2015

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (Chantal Akerman, 1975)

Delphine Seyrig in Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (Chantal Akerman, 1975)

Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Jan Decorte, Henri Storck, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, Yves Bical. Screenplay: Chantal Akerman. Cinematography: Babette Mangolte. Art direction: Philippe Graff. Film editing: Patricia Canino.

Jeanne Dielman (to shorten its unwieldy title) is a film experiment (which is not at all the same thing as an experimental film). Akerman tests the medium to see whether a story can be told without melodrama, without the usual editing cuts that shift point of view within dialogue, without excess camera movement, without a music soundtrack, without all the cinematic techniques that we have come to rely upon. She also tests the audience, to see if they will sit through a 201-minute film in which minutes go by without anything more interesting happening than a woman taking a bath, washing the bathtub, peeling potatoes, preparing dinner, eating it with her son, washing dishes, and so on -- all in long takes with no cuts and no apparent forward narrative drive. The answer as far as the medium is concerned is an emphatic yes, a story can be told that way. As for the audience, that's a difficult question to answer. I wouldn't recommend it to anyone who doesn't have a high tolerance for cinematic riddles, or who can't sit raptly looking at a painting in a museum for minutes on end -- for this is a film that draws on visual patience in the way that great works of painting do. Most of the scenes are filmed straight on, as if looking at them through a frame. In short, Akerman treats a kinetic medium, motion pictures, as if it were a static medium like painting. Is it the greatest film of all time, as has been claimed? I think it's at least a great film, but I don't have any urgent desire to see it again soon. What it did to me was make me aware of watching, of patiently waiting to see what image would be presented to me next, what piece of the puzzle that is Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig) would fall into place. It takes place over the course of three days, on the first of which Jeanne presents herself as a supremely capable and precise person, going through the motions of her daily existence (which include receiving a man into her bedroom, because she makes a living for herself and her son by discreet prostitution) with calm efficiency. On the first two days, we don't follow her into the bedroom with her client, but the camera lingers in the hall, looking at the bedroom door, until the light fades enough to indicate a passage of time, whereupon she and the man emerge from the bedroom and go to her apartment door, where he pays her and indicates that he will see her again in a week. She then goes to her dining room and puts the money in a blue-and-white tureen, whose lid makes a satisfying clink when she covers it. (In the absence of a music track, ambient sounds take on a greater role.) Later, her son, Sylvain (Jan Decorte), comes home from school and they have dinner, listen to the radio, go out for a walk, and come back home to rearrange the living room furniture so he can unfold the sofa for his bed. They go to sleep. But because many of these incidents are presented in real time, we are allowed to examine them in detail, to notice the furnishings of the apartment and the lack of affect of both mother and son, who have settled into a routine. We also notice the way a blue light, apparently from a sign outside their apartment, bounces off the surfaces of the furniture: It flashes and flickers in a way that suggests a rhythmic repetition but never quite resolves itself into a pattern. In that regard it's unlike Jeanne and Sylvain, who clearly have a pattern to their lives. And that's why it's a shock on the second day -- which begins about an hour into the film -- when Jeanne fails to do up a button on her housedress, something that Sylvain brings to her notice. Or later, when other elements of the pattern of her life don't fall in place: She burns the potatoes she is preparing for dinner; she forgets to switch off a light when she moves from room to room; she fails to put the cover on the tureen after putting the money from the second day's client into it. In any other context than the one established by the first day depicted in the film, these details would be insignificant. But Akerman makes them significant, even troubling, by having made us aware of the cold precision of Jeanne's routine. That this eventually builds to a remarkable climax (I use the word advisedly but not facetiously) is made possible by the mastery with which Akerman has set up her film. I kept wondering what Alfred Hitchcock, the master of voyeurism in cinema, might have made of Jeanne Dielman, a film that makes voyeurs of us all.

Monday, November 9, 2015

Love and Anarchy (Lina Wertmüller, 1973)

Sunday, November 8, 2015

Salaam Bombay! (Mira Nair, 1988)

Saturday, November 7, 2015

Gigi (Jacqueline Audry, 1949)

Friday, November 6, 2015

Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966)

|

| Nikolay Burlyaev in Andrei Rublev |

Daniil Chyornyi: Nikolay Grinko

Theophanes the Greek: Nikolay Sergeyev

Boriska: Nikolay Burlyaev

Kirill: Ivan Lapikov

Durochka: Irma Raush

Prince Yuri/Prince Vasiliy: Yuriy Nazarov

Patrikei: Yuriy Nikilin

The Jester: Rolan Bykov

Foma: Mikhail Kononov

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Screenplay: Andrey Konchalovskiy, Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography: Vadim Yusov

Production design: Evgeniy Chernyaev

Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov

Has any filmmaker ever made more eloquent use of the widescreen format than Andrei Tarkovsky does in Andrei Rublev? It was a process developed by Hollywood to help win its war with television -- bigger naturally assumed to be better. In Hollywood, it usually went hand-in-hand with color, and although the various widescreen processes -- Cinerama, Cinemascope, VistaVision, etc. -- were used in black-and-white films, they often feel out of place today. A case in point: The Diary of Anne Frank (George Stevens, 1959), which won an Oscar for the cinematography of William C. Mellor, but which seems to cry out for a format less expansive than CinemaScope, in which the Frank family's attic seems far too spacious. Andrei Rublev was filmed in a process called Sovscope, which like CinemaScope used anamorphic lenses to produce a 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Tarkovsky and cinematographer Vadim Yusov artfully work with the expanse of the screen, not shying away from closeups but also doing extraordinary movement with the camera. One of the earliest scenes takes place in the barn in which Rublev and his fellow artist-monks take shelter from the rain. We are given an astonishing 360-degree pan inside the barn, circling from the monks to the other denizens of the shelter and back to the monks, a study in faces that establishes one of the film's major subjects: the nature of Russian humanity, which also becomes an abiding concern of Rublev's. (I think there's a witty acknowledgment of the nature of widescreen in that the peep-hole cut into the wall of the bar seems to have the same aspect ratio as the film.) And in the concluding sequence, there is a magnificent pan from the gates of the walled city of Vladimir below and the emerging procession up to the structure that holds the newly cast bell, where Boriska waits anxiously. Andrei Rublev is one of those films I can't help rewatching; even though (or perhaps because) it's slow and challenging, it more than repays frequent viewings. Tarkovsky is not a director to be taken lightly, and the moment you begin to be lulled by the magnificence of Yusov's cinematography or Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov's score, the director is likely to shock you with images of cruelty and brutality but also of beauty that make you sit upright. A "trigger warning" might be especially needed for lovers of animals, given the harshness with which they are occasionally treated: There is a scene with a cow on fire that will likely haunt me for a long time. But all the unpleasantness in the film is in service of a story about the persistence of the Russian people and the transcendence of art. Anatoliy Solonitsyn, who plays Rublev, looks a bit like Viggo Mortensen, and recalls for me the tormented masculinity you find in some of Mortensen's performances. Another standout performance is given by Tarkovsky's wife, billed as Irma Raush, as the "holy fool" Durochka, whom Rublev saves from a massacre by the Tatars by killing the assailant -- leading Rublev to atone by giving up his painting and taking a vow of silence. The last section of the film is given over to young Boriska, played by Nikolay Burlyaev, the astonishing Ivan in Tarkovsky's Ivan's Childhood (1962), who takes on the task of casting a church bell despite the suggestion that he will be murdered by the tyrannical Grand Prince if he fails. Although the film is in black-and-white, it concludes with a breathtaking color sequence in which Rublev's paintings are shown in close-up. (To my mind, this final ecstatic survey of Rublev's work is the only section in which Tarkovsky is thwarted by the widescreen process: Rublev's paintings had an aspiring verticality that is at odds with the dimensions of the screen.)

Thursday, November 5, 2015

Coquette (Sam Taylor, 1929)

Wednesday, November 4, 2015

No End (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1985)

Tuesday, November 3, 2015

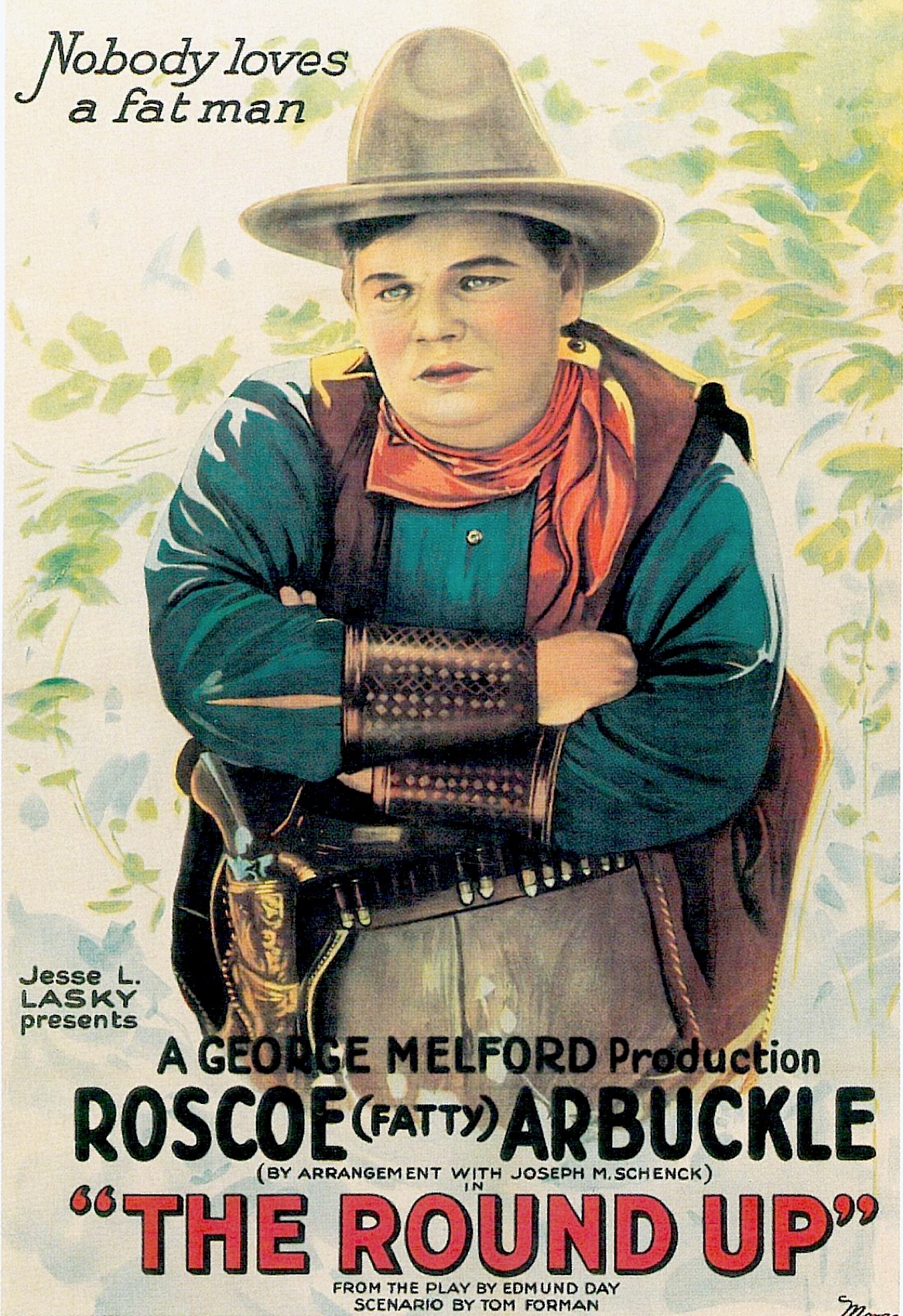

Two With Roscoe Arbuckle

"Nobody loves a fat man," the kicker line for Arbuckle's 1920 feature, was meant to be wistfully ironic, since at the time, everybody loved "Fatty" Arbuckle (a nickname he hated). The irony went from wistful to bitter in a couple of years, when the scandal surrounding the death of Virginia Rappe turned Arbuckle into one of the country's most despised men, bringing his career to a halt. But when The Round-Up was made, Arbuckle was so popular that he received the featured billing for a film in which he was a supporting player, the comic relief in a somewhat routine Western. Arbuckle plays the sheriff in a small Arizona town, where he's much admired because he uses his dexterity, rather than his fists or guns, to disarm the bad guys. But he's painfully shy around women, which is why he loses the girl he loves (Jean Acker) to someone else. The main story revolves around a prospector (Irving Cummings) who is thought to be dead, so his girlfriend (Mabel Julienne Scott) marries someone else. Meanwhile, a lot of trouble gets stirred up by the "half-breed" Buck McKee (Wallace Beery). Things get sorted out eventually after a lot of chases and gunfights. Arbuckle and Beery are the best things in the movie, along with some location scenery handsomely photographed by Paul P. Perry.

The Life of the Party (Joseph Henabery, 1920)

As a knockabout comedy more in the Arbuckle mainstream, The Life of the Party seems designed largely to provide him with an opportunity to dress up in children's party clothes. The plot has to deal with a women's group who are out to bust up a trust that fixes the price of milk. Arbuckle plays Algernon Leary, an unscrupulous lawyer who is at first willing to go along with the trust, but is converted to their side by a pretty young member of the group (Viora Daniel). She also happens to be engaged to a judge (Frank Campeau) who, unknown to her, is in the pockets of the milk trust. This leads to much farcical running around, especially after the women's group decides to throw a fundraising party to which everyone is expected to come dressed as babies. It all goes on too long. The cast includes Roscoe Karns, an actor who didn't really come into his own until sound arrived, giving him the chance to reel off snappy patter for Howard Hawks in Twentieth Century (1934) and His Girl Friday (1940).

|

| In Life of the Party, Arbuckle attends a party in which the guests dress as babies. |

poster.jpg)