A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, March 31, 2016

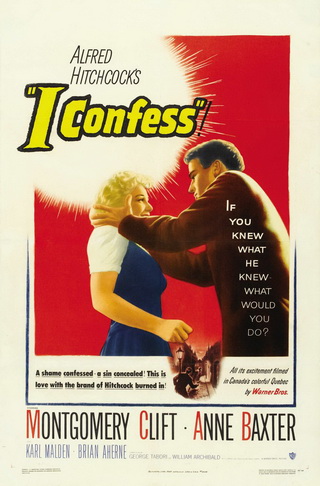

I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock, 1953)

I Confess is generally recognized as lesser Hitchcock, even though it has a powerhouse cast: Montgomery Clift, Anne Baxter, and Karl Malden. It also has the extraordinary black-and-white cinematography of Robert Burks, making the most of its location filming in Québec. Add to that a provocative setup -- a priest learns the identity of a murderer in confession but is unable to reveal it even when he is put on trial for the murder -- and it's surprising that anything went wrong. I think part of the reason for the film's weakness may go back to the director's often-quoted remark that actors are cattle. This is not the place to discuss whether Hitchcock actually said that, which has been done elsewhere, but the phrase has so often been associated with him that it reveals something about his relationship with actors. It's clear from Hitchcock's recasting of certain actors -- Cary Grant, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Ingrid Bergman -- that he was most comfortable directing those he could trust. And Clift's stiffness and Baxter's mannered overacting suggest that Hitchcock felt no particular rapport with them. But I Confess also played directly into the hands of the censors: The Production Code was administered by Joseph Breen, a devout Catholic layman, and routinely forbade any material that reflected badly on the clergy. In the play by Paul Anthelme and the first version of the screenplay by George Tabori, the priest (Clift) and Ruth Grandfort (Baxter) have had a child together, and the murdered man (Ovila Légaré) is blackmailing them. Moreover, because he is prohibited from revealing what was told him in the confessional and naming the real murderer (O.E. Hasse), the priest is convicted and executed. Warner Bros., knowing how the Breen office would react, insisted that the screenplay be changed, and when Tabori refused, it was rewritten by William Archibald. The result is something of a muddle. Why, for example, is the murderer so scrupulous about confessing to the priest when he later has no hesitation perjuring himself in court and then attempting to kill the priest? No Hitchcock film is unwatchable, but this one shows no one, except Burks, at their best.

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Scenes From a Marriage (Ingmar Bergman, 1973)

|

| Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann in Scenes From a Marriage |

Tuesday, March 29, 2016

Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958)

Monday, March 28, 2016

Schindler's List (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

Amid the nearly universal acclaim for Schindler's List, two major criticisms are often heard. One is that Spielberg tends toward the sentimental, especially at the end of the film: He lets Schindler's remorse at having not been able to save more Jews from the Holocaust go on too long, and the appearance of the surviving Schindlerjuden with the actors who played them is an unnecessary extension of the film's already clear moral statement, blurring the distinction between documentary and fictionalized narrative. The other objection is that the appearance of the girl in the red coat during the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto is a too-showy use of film technique in what should be a gripping, realistic scene. The former objection is a highly subjective one: For many, the film needs something to soften the harshness of the story's catharsis. For others, the answer is simply, "Let Spielberg be Spielberg," a gifted but traditional storyteller whose vision of the material he chooses is invariably personal. It's the second objection that gets to the heart of what film criticism is all about. I think David Thomson, in his brief essay on Schindler's List in Have You Seen ... ?, puts the objection most provocatively when he observes, "With that one arty nudge Spielberg assigned his sense of his own past to the collected memories of all the films he had seen. All of a sudden, the drab Krakow vista became a set, with assistant directors urging the extras into line.... It was an organization of art and craft designed to re-create a terrible reality done nearly to perfection. But in that one small tarting up ..., there lay exposed the comprehensive vulgarity of the venture." I can't be as harsh as Thomson, for one thing because when I saw the film in the theater shortly after its release in 1993, I didn't notice the red coat -- the one note of color in the middle of the black-and-white film -- because I am mildly red-green colorblind. (It's difficult to explain to the non-colorblind, but those of us with the color deficiency usually see the color in question, but it's not quite the same color that the normally sighted see.) I did, however, notice the little girl: The framing by Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski puts her in the center of the action and makes her search for a hiding place evident even in a long shot. What I did miss that time was the reappearance of the girl's body in a stack of corpses later in the film, something that would be evident to anyone who had earlier seen the red of the coat. Later, when I saw the film on video, after having read about the controversy over the red highlight, I was able to perceive the color -- not so intense for me as perhaps for you, but once brought to my attention inescapable -- and to be shocked by its reappearance in the later scene. But only when I watched the film again last night did I realize the function of the "arty nudge": When we first see the girl in the red coat, we see her from the point of view of Schindler (Liam Neeson) himself, on a hillside above the ghetto. And when we see her body, we are seeing it again from the point of view of Schindler, visiting the cremation site where Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes) has been ordered to burn the bodies of those killed in the liquidation of the ghetto. It is a subtle but effective move because it coincides with (or perhaps precipitates) Schindler's decision to try to save as many of his Jewish workers as he can. Is it "arty" or "tarting up" or "vulgar"? Perhaps it is, but it's also effective filmmaking. And only the fact that the Holocaust remains so large and sacrosanct an event in the moral history of the West raises the question of whether "effective filmmaking" is inappropriate to such a subject.

Sunday, March 27, 2016

A Man Escaped (Robert Bresson, 1956)

|

| François Leterrier in A Man Escaped |

François Jost: Charles LeClainche

Orsini: Jacques Ertaud

Blanchet: Maurice Beerbeck

Le Pasteur: Roland Monod

Director: Robert Bresson

Screenplay: Robert Bresson

Based on a memoir by André Devigny

Cinematography: Léonce-Henri Burel

Production design: Pierre Charbonnier

Film editing: Raymond Lamy

"I don't laugh," Fontaine says. No, he doesn't. In fact, throughout A Man Escaped, François Leterrier's expression rarely changes. But we always know the determination, the doubt, the calculation, the suspicion that's going through his head, thanks to Leterrier's use of his eyes.* But as Eisenstein taught us so long ago, montage is responsible for so much of what we feel and witness in movies, and we have to credit Raymond Lamy's editing as well as Léonce-Henri Burel's cinematography and of course Robert Bresson's direction for making A Man Escaped, based on the memoirs of André Devigny, a member of the French Resistance who was imprisoned by the Nazis, one of the most powerful excursions into a man's soul ever put on film. The word "minimalism" was not so much in use when A Man Escaped was made as it is today, but if ever a film was minimalist in avoiding conventional movie tricks like background music or flashy camerawork, it's this one. Bresson's restraint as a filmmaker serves to keep us in Fontaine's head, blotting out all but his grim determination to escape. When Fontaine murders the prison guard, we don't see it. We barely even hear it. We are watching a blank wall when it happens. But we hold our breaths while it does. Today we think of the prison-break movie genre in terms of films like Stalag 17 (Billy Wilder, 1953), The Great Escape (John Sturges, 1963), Escape From Alcatraz (Don Siegel, 1979), and The Shawshank Redemption (Frank Darabont, 1994), with stars like William Holden, Steve McQueen, Clint Eastwood, Tim Robbins, and Morgan Freeman, with action leavened by comic relief and made more tense by grotesque and sadistic guards, and underscored by mood music. What Bresson gives us is a film with no stars that concentrates largely on the face of the man planning his breakout and whose only music is the occasional underscoring with the "Kyrie" from Mozart's C-minor mass. And it works far better than those more famous and conventional movies.

*Leterrier went on to become a film director and writer. He made only one more film appearance as an actor, in the small role of André Malraux in Alain Resnais's Stavisky... (1974).

The Manchurian Candidate (John Frankenheimer, 1962)

Although Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964) is by far the more celebrated film, I think as satire The Manchurian Candidate is a more subtle and sophisticated response to the Cold War. It may have fallen out of favor too soon because its subject, political assassination, became so sensitive just a month after its release, when John F. Kennedy was shot. For reasons that remain unclear, including Frank Sinatra's purchase of the distribution rights, it fell out of release for a long time, and only resurfaced occasionally on television until 1987, when, after a screening at the New York Film Festival, it became available on video. It's a loopy, scary, often hilarious, sometimes puzzling, and -- especially in any election year -- absolutely essential American film. Frankenheimer, who was one of the pioneers of American television drama in the age of shows like Playhouse 90, never developed a distinctive style in his movie work, but he knew how to tell a story, even when the story is as convoluted as this one. With George Axelrod, he adapted the 1959 thriller by Richard Condon, sometimes lifting dialogue direct from the novel. The results are occasionally enigmatic, as in the meeting of Marco (Sinatra) with Eugenie Rose Chaney (Janet Leigh) on the train, where the dialogue shifts into the surreal and seems to be laden with code. In terms of plot, the encounter -- probably the oddest meeting on a train since Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint's characters met in North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock, 1959) -- goes nowhere: Leigh's character serves no further discernible role in the narrative. But it serves nicely to keep the viewer off guard as things grow increasingly bizarre. The weakest performance in the film is probably that of Laurence Harvey as Raymond Shaw. Harvey can't seem to be bothered to keep up an American accent, but somehow even that fits the ambiguity of his character. Angela Lansbury, as Raymond's mother (this is the point where it's usual to mention that she was only three years older than Harvey), is absolutely terrifying as one of the movies' greatest female villains. It earned her an Oscar nomination, but she lost to Patty Duke in The Miracle Worker (Arthur Penn). James Gregory, as her Joe McCarthy-like husband, would not be out of place in the current presidential campaign.

Saturday, March 26, 2016

Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Back in the day we would discuss for hours the significance of Thomas (David Hemmings) fetching an invisible tennis ball after having photographed an invisible murder. Then later we scrutinized the thematic relationship of Blow-Up to Antonioni's great trilogy of L'Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L'Eclisse (1962). More recently, Blow-Up has figured large in discussions of the "male gaze." But lately it has become a historical artifact from a time and place half a century ago, the "swinging London" of the mid-1960s. And there I think it best belongs. What perhaps needs to be discussed is the tone of the film: Is it a document, or a celebration, or an exposé, or a satire? I think it is a bit of all of these, but mostly the tone is satiric. Thomas's aesthetic detachment, not to say voyeurism, makes him the perfect vehicle for an exploration of the era, from the grim flophouse he spends a night photographing to the drug-addled home of the wealthy, by way of a fashion shoot, a glimpse of what seems to be adulterous affair but may be a murder, a mini-orgy with some teenyboppers, a peek at two of his friends making love, and a performance in a rock club. All of it viewed with the impassive gaze of Thomas, Antonioni, and Carlo Di Palma's movie camera. Is it meant to be funny? Yes, sometimes, as when Thomas encounters the model Verushka at the party and says, "I thought you were supposed to be in Paris," and she replies, "I am in Paris." Or when we see the audience watching the performance of the Yardbirds in the club, showing no signs of enjoyment, but then going crazy when Jeff Beck smashes his guitar and flings it into the audience. Thomas escapes from the club with a piece of it, eludes the pursuing crowd, but throws it away when he realizes it's worthless. (A passerby picks it up, looks it it, and tosses it away.) It's a portrait of a cynical era in which people, as Oscar Wilde put it, know "the price of everything and the value of nothing." Hemmings, with his debauched choirboy* face, is the perfect protagonist, and Vanessa Redgrave, at the start of her career, is beautifully, magnificently enigmatic as the woman who may or may not have been involved in murder. I'm not sure it's a great film -- certainly not in comparison to Antonioni's trilogy -- but it will always be a fascinating one.

*Almost literally: Hemmings started as a boy soprano who was cast by Benjamin Britten in several works, most notably as Miles in the 1954 opera The Turn of the Screw. He can be heard on the recording made that year with Britten conducting.

*Almost literally: Hemmings started as a boy soprano who was cast by Benjamin Britten in several works, most notably as Miles in the 1954 opera The Turn of the Screw. He can be heard on the recording made that year with Britten conducting.

Friday, March 25, 2016

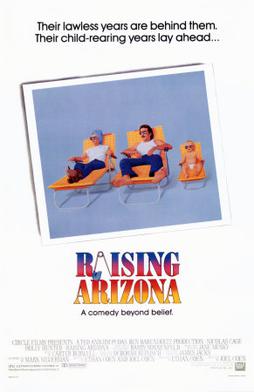

Raising Arizona (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 1987)

Raising Arizona was the Coen brothers' second movie, and they never made another quite as broadly comic as this one. Even The Big Lebowski (1998) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) seem restrained in comparison. I found that it took a little getting used to on this viewing: Everyone in it (including the baby) is a caricature, a live-action version of a Warner Bros. cartoon character. Maybe I reacted this way because I recently saw Holly Hunter in the deadly serious role of Ada in The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993) and had forgotten what a gifted farceuse she could be when she sets her tight little mouth in that determined line and barrels ahead. Nicolas Cage was still in that goofy hangdog persona he used in Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986) and only began to grow out of the next year in Moonstruck (Norman Jewison, 1987). But the real surprise for me was Frances McDormand, going completely over the top as Dot, the scatterbrained mother of the most odious bunch of brats ever seen on film. She was at the beginning of her career as a serious actress and would follow up Raising Arizona with her first Oscar nomination for Mississippi Burning (Alan Parker, 1988), so seeing her go all loosey-goosey in this film was a revelation. It's by no means among my favorite Coen brothers movies, and watching it in the company of their best -- among which I'd put Fargo (1996), No Country for Old Men (2007), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) -- would probably show up some of its flaws, but why would you want to do that? Sometimes silly fun is enough. At only a touch over an hour and a half, Raising Arizona doesn't hang around long enough to wear out its welcome.

Thursday, March 24, 2016

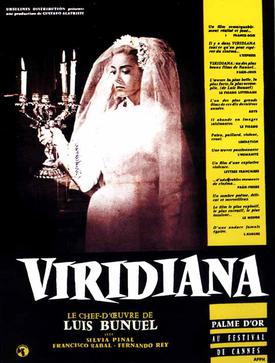

Viridiana (Luis Buñuel, 1961)

TCM this month has been running a series of movies condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, with commentary by Sister Rose Pacatte. Sister Rose doesn't have a lot of screen presence, but she does a good job of explaining why the Legion in its heyday found the movies objectionable -- and suggesting why they really aren't. It's hard to believe today that Viridiana, with its heavily moral tone, was once considered blasphemous, but ours is a day when anything sacred is routinely held up for scrutiny. It's the first work of Buñel's greatest period as writer-director, and while it doesn't quite rise to the exalted standard of Belle de Jour (1967) or The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), it wrangles effectively with their topics, including middle-class morality and the repressive element of Catholicism. Silvia Pinal gives the title role credibility, moving from naïveté through disillusionment to a final note of ambiguity: Has Viridiana truly fallen from the grace she has so ardently sought? The film is also a triumph of casting, not only in the key roles of Don Jaime (Fernando Rey), Viridiana's lecherous, tormented uncle, and Jorge (Francisco Rabal), his equally lecherous but profoundly untormented bastard son, but also Margarita Lozano as Ramona, Don Jaime's and later Jorge's maid-mistress, and Teresa Rabal as Rita, Ramona's sly, sneaky daughter, And then there's the gallery of grotesques, the beggars whom Viridiana naively takes in and tries to care for. Is there a more horrifying scene than the one that culminates in Buñuel's famous parody of Leonardo's The Last Supper, in which the beggars nearly destroy Don Jaime's house, which Jorge is trying to restore? It can be argued that the avaricious Jorge gets what's coming to him, of course, but Buñuel is never as simplistic as that, viz., the deep ambiguity of the closing scene in which the virtuous Viridiana has let down her hair and forms a threesome -- at the card table but where else? -- with Jorge and Ramona.

Wednesday, March 23, 2016

The King of Comedy (Martin Scorsese, 1982)

Is there anything scarier than Robert De Niro's smile? It's what makes his bad guys, like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976) or Max Cady in Cape Fear (Scorsese, 1991), so unnerving, and it's what keeps us on the edge of our seats throughout The King of Comedy. Rupert Pupkin isn't up to anything so murderous as Travis or Max, but who knows what restrains him from becoming like them? As a satire on the nature of celebrity in our times, Paul D. Zimmerman's screenplay doesn't break any new ground. But what keeps the movie from slumping into predictability are the high-wire, live-wire performances of De Niro and Sandra Bernhard as the obsessive fans and the marvelously restrained one of Jerry Lewis as late night talk-show host Jerry Langford, the object of their adulation. And, of course, Scorsese's ability to keep us guessing about what we're actually seeing: Is this scene taking place in real life, or is it a product of Rupert's deranged imagination? That extends to the movie's ending, in which Rupert, having kidnapped Langford and engineered a debut on network television, is released from prison and becomes a celebrity himself. Are we to take this as the film's comment on fame, like the phenomenon of Howard Beale in Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) and any number of people (many of them named Kardashian) who have become famous for mysterious reasons? (Incidentally, the odd thing about Rupert's standup routine is not that it's bad, but that it's exactly the sort of thing that one might have sat through while watching a late night show in 1982.) I prefer to think that we are still in Rupert's head at film's end -- it seems less formulaic that way. I don't know of a movie that stays more unbalanced and itchy from scene to scene.

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

The Piano (Jane Campion, 1993)

If Jane Campion had gone with her original plan, Ada (Holly Hunter) would have gone down with her piano like Ahab lashed to the whale. The comparison to Moby-Dick is not, I think, terribly far-fetched: The Piano is one of those works, like the Melville novel, that tempt one into symbolic interpretations. Ada's obsession with her piano is, in its own way, like Ahab's obsession with the white whale, a kind of representation of the extreme irrational nexus of mind and object. But in Campion's completed version, Ada loses only a finger, not her life, and the piano is replaced along with the finger. Does this resort to a happy ending vitiate Campion's film, or should we accept as a given that life does in fact sometimes work that way? I think in a movie as enigmatic as The Piano so often is, Campion has blunted the emotional impact by having Ada and Baines (Harvey Keitel) wind up together in what seems to be a pleasant home far from the wilderness in which most of the film takes place, she teaching piano with her hand-crafted prosthetic and learning to speak, as Flora (Anna Paquin), that devious, semi-feral child, turns cartwheels. (Flora puts me in mind of another child of the wilderness in another work of impenetrable symbolism, Pearl in The Scarlet Letter.) Happily ever after seems like a lie in the mysterious terms with which the film began. We never learn why Ada turned mute, or who Flora's father was and what happened to him, or why she agrees to move to New Zealand to marry and then spurn Stewart (Sam Neill), or find a way to resolve any number of other enigmas. But the great strength of the film lies its power to evoke the imponderable, to make us wonder about Baines's life among the Maori, about the persistence of an imperialist culture (women wearing hoopskirts and men in top hats) in an alien land, about the nature of awakening sexuality, about the function of art, about the tension between innocence and experience in a child's life, and so on. It is, I'm certain, a great film, just because it is so hard to grasp and reduce to a formula.

Links:

Anna Paquin,

Harvey Keitel,

Holly Hunter,

Jane Campion,

Sam Neill,

The Piano

Monday, March 21, 2016

The Devil's Eye (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

|

| Jarl Kulle and Bibi Andersson in The Devil's Eye |

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Sawdust and Tinsel (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

When this movie was first released in the United States it was called The Naked Night, probably by exhibitors who wanted to cash in on the reputation Swedes had gained for being sexy, but especially because the film's star, Harriet Andersson, had just appeared in the nude in Summer With Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953), which had been passed off in some markets as a skin flick. By the time I first saw it, sometime in the 1960s, it had been renamed Sawdust and Tinsel. (The Swedish title, Gycklarnas Afton, can be translated as something like "Evening of a Clown.") Frankly, the first time I saw it, I found it tedious and heavy-handedly sordid, with its shabby, bankrupt circus and its frustrated, destructive relationships. Having grown older and perhaps somewhat wiser, I don't hate it anymore, but I can't see it as the masterpiece some do. It seems to me to lean too heavily on the familiar trope of the circus as a microcosm of the world, and on emphasizing the grunge (sawdust) and fake glamour (tinsel) of its currently prevalent title. What it has going for it is the awesome cinematography by Sven Nykvist: It was his first film for Bergman; they didn't work together again until 1960 and The Virgin Spring, but it became one of the great partnerships in filmmaking. The opening sequence of the tawdry little circus caravan trundling across the landscape is superbly filmed, and I can't help wondering if Bergman and Gunnar Fischer, the cinematographer of The Seventh Seal (1957), didn't have it in mind when they created the iconic shot of Death and his victims silhouetted against the sky in that later film. The performances, too, are excellent: Åke Grönberg as Albert, the worn-out circus owner; Andersson as his restless mistress, Anne; Hasse Ekman as Frans, the actor who rapes her; Anders Ek as the half-mad clown, Frost; and Annika Tretow as Albert's wife, who has gone on to be a success in business after he left her. But the story is heavily formula-driven: There is, for example, a rather clichéd sequence in which Albert toys with suicide, which too obviously echoes an earlier moment when Frans hammily rehearses a scene in which he kills himself while Anne watches offstage. In the end, the movie is rather like a version of Pagliacci without the benefit of Leoncavallo's music. After a disastrous performance of the circus, someone actually says, "The show's over," which is pretty much a steal from the final line of Pagliacci: "La commedia è finita!"

Saturday, March 19, 2016

Moulin Rouge (John Huston, 1952)

If Moulin Rouge had a screenplay worthy of its visuals, it would be a classic. As it is, it's still worth seeing, thanks to a stellar effort to bring to life Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings and sketches of Parisian nightlife in the 1890s. The screenplay, by Anthony Veiller and director Huston, is based on a novel by Pierre Le Mure, the rights to which José Ferrer had purchased with a view to playing Lautrec. He does so capably, subjecting himself to some real physical pain: Ferrer was 5-foot-10 and Lautrec was at least a foot shorter, owing to a childhood accident that shattered both his legs, so Ferrer performed many scenes on his knees, sometimes with an apparatus that concealed his lower legs from the camera. But that is one of the least interesting things about the movie, as is the rather conventional story of the struggles of a self-hating, alcoholic artist. What distinguishes the film is the extraordinary production design and art direction of Marcel Vertès and Paul Sheriff, and the dazzling Technicolor cinematography of Oswald Morris. Vertès and Sheriff won Oscars for their work, but Morris shockingly went unnominated. The most plausible theory for that oversight is that Sheriff clashed with the Technicolor consultants over his desire for a palette that reproduced the colors of Lautrec's art: The Technicolor corporation was notoriously persnickety about maintaining control over the way its process was used. It's possible that the cinematography branch wanted to avoid future hassles with Technicolor by denying Morris the nomination. (Ironically, one of the more interesting incidents from Lautrec's life depicted in the film involves his clashes with the lithographer over the colors used in posters made from his work.) The extraordinary beauty of the film and some lively dance sequences that bring to life performers such as La Goulue (Katherine Kath) and Chocolat (Rupert John) make it memorable. There are also good performances from Colette Marchand as Marie Charlet and Suzanne Flon as Myriamme Hayam. And less impressive work from Zsa Zsa Gabor, playing herself more than Jane Avril, and lipsynching poorly to Muriel Smith's voice in two songs by Georges Auric.

Friday, March 18, 2016

A Lesson in Love (Ingmar Bergman, 1954)

|

| Eva Dahlbeck and Gunnar Björnstrand in A Lesson in Love |

David Erneman: Gunnar Björnstrand

Susanne Verin: Yvonne Lombard

Nix Erneman: Harriet Andersson

Carl-Adam: Åke Grönberg

Prof. Henrik Erneman: Olof Winnerstrand

Svea Erneman: Renée Björling

Pelle: Göran Lundquist

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography: Martin Bodin

In A Lesson in Love, Ingmar Bergman seems to be trying to turn Eva Dahlbeck into Carole Lombard. She certainly has Lombard's blond glamour, and she makes a surprising go at knockabout comedy. But where Lombard had the light touch of a Howard Hawks or an Ernst Lubitsch to guide her in her best work, Dahlbeck is in the hands of Bergman, whose touch no one has ever called light. A year later, the Bergman-Dahlbeck collaboration would make a better impression with Smiles of a Summer Night, but A Lesson in Love sometimes verges on smirkiness in its treatment of the marriage of Marianne and David Erneman. They are on the verge of divorce and she is about to marry her old flame Carl-Adam, a sculptor for whom she once posed. David is a gynecologist who has had a series of flings with other women, including Susanne, with whom he is trying to break up. But Marianne has not exactly been faithful to their vows either. Meanwhile, we also get to know their children, Nix and her bratty little brother, Pelle, and David's parents, who in sharp contrast to Marianne and David are celebrating 50 years of marriage. While Bergman sharply delineates all of these characters -- especially 15-year-old Nix, who hates being a girl so much that she asks her father if he can perform sex-change operations -- the semi-farcical situation he puts them has a kind of aimless quality to it. I appreciated Harriet performance as Nix the more for having seen her as the dying Agnes in Bergman's Cries and Whispers (1972) the night before, but in this film her role makes no clear thematic sense.

Thursday, March 17, 2016

Cries and Whispers (Ingmar Bergman, 1972)

Cries and Whispers is both of a time and timeless. It is very much a product of the last great moviegoing age, when people would see a challenging film and go back to their homes or coffee shops or dorm rooms and debate what it meant. Today, if a movie provokes discussion it's usually on social media, where seriousness gets short shrift. Moreover, the discussion is likely to get interrupted by someone who has just seen the latest installment of some hot TV series and wants to try out their theories. Moreover, the combination of visual beauty and emotional rawness in Bergman's film is something rarely encountered today. We are, I think, wary of emotion, too eager to lapse into ironic distancing from the depiction of disease, suffering, death, cruelty, passion, spite, and grief that permeates Cries and Whispers. No director I know of is trying to do what Bergman does in so unembarrassed a fashion in this movie. And that, in turn, is what makes it timeless: The emotions on view in the film are universal, and Bergman's treatment of them without melodrama or sentiment is unequaled. Personal filmmaking is becoming a lost art: There are a few prominent adherents to it today, such as Paul Thomas Anderson or Terrence Malick, and their films are usually greeted with a sharp division of opinion between critics who find them pretentiously self-indulgent and those who find them audaciously original. But we seldom see performances as daring as Harriet Andersson's death scene, Kari Sylwan's attempts to comfort her, Ingrid Thulin's self-mutilation, and Liv Ullmann's confrontations with the others. And we seldom see them in a narrative that teeters between realism and nightmare as effectively as Bergman's screenplay, in a setting so evocative as production designer Marik Vos-Lundh's, or via such sensitive camerawork as Sven Nykvist's. The film has often been compared to Chekhov, and for once it's a film that merits the comparison.

Wednesday, March 16, 2016

Big Eyes (Tim Burton, 2014)

It's a great idea for a movie: the downfall of a hugely successful artist who took the credit for the work done by someone else. It allows a filmmaker to explore such topics as fraud, the difference between capital-A Art and works that are just popular, the nature of value when it comes to works of the imagination, and in this case, the relationship between men and women. Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz) persuaded his wife, Margaret (Amy Adams), to let him pass off her work -- paintings of large-eyed waifs -- as his own. The trouble with the movie is that it never quite decides what it wants to say about any of the important issues it raises, other than that Margaret Keane was a victim of the male-dominated society of the 1950s and '60s. It doesn't even settle on the issue of whether Margaret's paintings were mawkish kitsch or actual works of Art, though I think it rather smugly assumes that viewers will be smart enough to have decided on the former. But it complicates this position by starting with a quote from Andy Warhol proclaiming that the Keane art is "terrific! If it were bad, so many people wouldn't like it." And it turns the critics of Keane into pretentious snobs, represented by the gallery owner (Jason Schwartzman) who resents the fact that the Keane paintings outsell his rather arid, minimalist abstractions, and by John Canaday (Terence Stamp), the New York Times critic who prevents a Keane from being exhibited at the 1964 World's Fair in New York. So what we are left with is Margaret Keane, the victim who finally has the courage to turn against her monstrously manipulative husband and become a hero. That she is a hero in the cause of women's rights is presumably fine. But is it also fine that she becomes a hero by asserting her right to profit from making bad art? I don't think either screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski or director Tim Burton have decided for themselves. So we are left only with Adams's terrific performance as Margaret, which could have been bolstered by a fuller backstory, and Waltz's somewhat overdone performance as Walter. What Burton does best in his movies is milieu, especially when he can caricature it, which he does here, with a little more restraint than usual, in his portraits of the business of art in the 1960s. And he gets us into the head of Margaret Keane: When she is grinding out big-eyed paintings for Walter she goes to a supermarket and hallucinates the clerks and customers as big-eyed grotesques. But the movie probably should have gone more in one direction or another: Either into a realistic portrayal of the relationship of the Keanes or into a more vivid and surreal lampoon of the art world. Trying to do a bit of both undermines the film.

Tuesday, March 15, 2016

The Story of Temple Drake (Stephen Roberts, 1933)

William Faulkner claimed that he wrote the novel Sanctuary for the money, which may have some truth in it -- it was one of his few best-selling novels. But if it's not on a par with The Sound and the Fury or As I Lay Dying or Go Down, Moses, it's a well-wrought book with a good deal more art than its sensational plot suggests: Temple Drake is a hedonistic Ole Miss coed who winds up at a bootlegger's hangout after an automobile accident and is abducted by a thug called Popeye who rapes her with a corncob (he's impotent) and forces her into prostitution. Naturally, Hollywood jumped at the chance to capitalize on the book's reputation, and equally naturally found itself unable to do anything but bowdlerize the story. Temple (Miriam Hopkins) is still a "bad girl," but gone are Popeye's impotence and the corncob, along with his name (presumably to avoid a lawsuit from the holders of the copyright on the cartoon character). In the movie he's called Trigger (Jack La Rue), and although the rape takes place (after a fadeout) in a corncrib, there's no hint of his incapacity. And in the end, Temple gets a chance to redeem herself in court at the trial of a man accused of the murder that Trigger actually committed -- a complete reversal of what happens in the book. Nevertheless, the film became one of the most notorious of the Pre-Code films that led to Hollywood's rigorous system of self-censorship. The problem is that it's a rather muddled movie. Roberts was a second-string director, and he fails to impose shape or coherence on the story, which was adapted by Oliver H.P. Garrett. Hopkins, in her 30s, is miscast as the flighty young Temple, and William Gargan, who plays the lawyer Stephen Benbow, alternately chews the scenery and fades into the background. La Rue, on the other hand, had a long career as a heavy and brings real menace to the part of Trigger, almost evoking Faulkner's description of Popeye's "vicious depthless quality of stamped tin." The best performance, though, is probably Florence Eldridge's as the downtrodden Ruby, who grudgingly tries to protect Temple from Trigger and the other men at the bootlegger's hangout. There is some Paramount gloss on the film: When she isn't in her underwear, Hopkins wears gowns by Travis Banton, and the cinematography by Karl Struss gives the movie a more sophisticated look than it really deserves. But the general feeling one gets is that Faulkner has once again been badly served by the movies.

Monday, March 14, 2016

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Would there have been a Quentin Tarantino if there hadn't been a David Lynch? Blue Velvet represents an opening up of mainstream moviemaking to the perverse underside of American experience. It had been approached before, in 1940s film noir, for example, but only by suggestion. In the era of the nascent Cold War, unusual sexual behavior was typically presented as the product of decadent cities like New York and Los Angeles. But in Lynch's film, made at the height of the Reagan era, it underlies the wholesome atmosphere of a small town where the fireman smiles and waves as he passes by. The film noir detective was disgusted by what he saw, not fascinated and drawn in the way Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) is. Jeffrey, barely out of adolescence, teams up to explore the mystery of Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) with a teenage girl, Sandy (Laura Dern), who is both disgusted and fascinated by what she learns. The use of songs like Bobby Vinton's "Blue Velvet" and Roy Orbison's "In Dreams" suggests the way American pop culture, aimed at the young, floats atop a sea of darkness that it only thinly hides. In the end, of course, everything is cleaned up: the vicious Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) gets what's coming to him and Dorothy is reunited with her child. Even Jeffrey's father, incapacitated by a stroke while watering his lawn at the beginning of the film, is restored to health. Sandy has earlier told us about her nightmare in which the horrors will only disappear when the robins fly down and bring a "blinding light of love." So in the end a robin appears on the windowsill, with one of the disgusting insects we saw at the film's beginning under the grass of the Beaumonts' lawn in its mouth. But Lynch mocks the happy ending by clearly showing us that it's a fake, an animated stuffed robin.

Sunday, March 13, 2016

A Room With a View (James Ivory, 1985)

|

| Rosemary Leach, Daniel Day-Lewis, Simon Callow, Helena Bonham Carter, Rupert Graves in A Room With a View |

Charlotte Bartlett: Maggie Smith

George Emerson: Julian Sands

Mr. Emerson: Denholm Elliott

The Rev. Mr. Beebe: Simon Callow

Eleanor Lavish: Judi Dench

Cecil Vyse: Daniel Day-Lewis

Mrs. Honeychurch: Rosemary Leach

Freddy Honeychurch: Rupert Graves

Director: James Ivory

Screenplay: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

Based on a novel by E.M. Forster

Cinematography: Tony Pierce-Roberts

Production design: Brian Ackland Snow, Gianni Quaranta

Music: Richard Robbins

Costume design: Jenny Beavan, John Bright

James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant had a collaboration that began with the formation of Merchant Ivory Productions in 1961 and lasted until Merchant's death in 2005. It usually included the screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. The trio developed a reputation for literary adaptations that were beautifully filmed with opulent sets and costumes and a gallery of celebrated stars -- most of them British. But the trouble with developing a distinctive style is that you can become a cliché: "Merchant Ivory" eventually became a label for a film that was tastefully middlebrow -- well-done and entertaining but just a tad safe. It's a pity, because their best films -- Howards End (1992), The Remains of the Day (1993), and this one -- set a high standard, despite their "safeness." Few films have a better sense of place and time than A Room With a View, in its depiction of Florence at the start of the 20th century. Granted, it leans a bit too heavily on the cliché about stuffy Brits losing their cool in the warmer climate of Tuscany, but that's the fault of E.M. Forster's novel -- not one of his major works -- and not of Jhabvala's Oscar-winning screenplay. Oscars also went to the art direction team and to costumers Jenny Beavan and John Bright, and it was nominated for best picture, for the supporting performances of Denholm Elliott and Maggie Smith, for Ivory's direction, and for Tony Pierce-Roberts's cinematography. The cast includes Helena Bonham Carter (in her "corset-roles" period) and Julian Sands, along with a then little-known Daniel Day-Lewis. Proof that Day-Lewis is one of the greatest actors of all time is no longer needed, but it's worth contemplating that he created the character of the prissy Cecil Vyse in this film within a year of appearing as the gay street punk Johnny in My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears), and that he would follow with the sexy Tomas in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Philip Kaufman, 1988), the paralyzed Christy Brown in My Left Foot (Jim Sheridan, 1989), and the dashing Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans (Michael Mann, 1992). Day-Lewis's Cecil Vyse verges on a caricature of the sexually repressed Brit, but he has an affecting moment near the end when, after Lucy (Bonham Carter) breaks off their engagement, he emerges as a vulnerable, three-dimensional character. Richard Robbins's fine score is memorably supplemented by Kiri Te Kanawa's recordings of two Puccini arias: "O mio babbino caro" from Gianni Schicchi and "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta" from La Rondine.

Saturday, March 12, 2016

Inside Out (Pete Docter and Ronnie Del Carmen, 2015)

Nessun maggior dolore / Che ricordarsi del tempo felice / Nella miseria -- There's no greater sorrow than remembering happy times in misery. What was true of Paolo and Francesca, Dante's lovers in hell, is also true of 11-year-old Riley (Kaitlyn Dias) in Inside Out. This extraordinarily clever Pixar animated movie, written by Docter, Del Carmen, Meg LeFauve, and Josh Cooley, takes an ancient premise and does wonderful things with it. Though it purports to be a whimsical treatment of modern psychological theories about the role of emotions in the formation of personality, it's a kind of moral allegory, not unlike the moral fables of all eras, including John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Riley and her parents (Diane Lane and Kyle MacLachlan) have moved to San Francisco from Minnesota. The shock of adjusting to a new home and a new school plunges Riley into misery, made worse by her remembrances of the happy times when she felt secure, had friends, and was a star on her hockey team. Her emotions -- Joy (Amy Poehler), Sadness (Phyllis Smith), Fear (Bill Hader), Anger (Lewis Black), and Disgust (Mindy Kaling) -- lose control of her personality, and things begin to fall apart. It's an astute and original (despite its ancient precedents) look at the way we learn to face life, brilliantly animated and skillfully voiced by a great cast.

Friday, March 11, 2016

Day for Night (François Truffaut, 1973)

Day for Night has a certain notoriety as the film that caused a rift between the New Wave directors Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. As the story goes, Godard walked out of a screening of Day for Night and charged that Truffaut had a fraudulent, sentimental view of the traditional movie-making that had been their targets in their first features, The 400 Blows (Truffaut, 1959) and Breathless (Godard, 1960). Godard, the purist, had maintained his radical political leftism from the beginning; Truffaut, who was an unabashed fan of movies no matter what their politics, had not maintained, in Godard's view, a strict enough awareness of his social responsibility as a filmmaker as his career advanced. Godard is, on his own terms, accurate about this aspect of Truffaut's work, so it all boils down to which filmmaker you prefer. As I happen to love them both, I won't take sides. Godard shows me things in movies that I haven't seen anywhere else, while Truffaut's humanity wins me over almost every time. Day for Night was, as it happens, a fair target for Godard's kind of criticism: It was warmly embraced by the establishment that Godard scorned, namely the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which gave it the best foreign language film Oscar for 1973 and, because of eligibility rules, led a year later to nominations for Truffaut as best director and (with Jean-Louis Richard and Suzanne Schiffman) for best original screenplay, as well as a best supporting actress nomination for Valentina Cortese. (She lost to Ingrid Bergman in Sidney Lumet's Murder on the Orient Express, leading to a famous moment in which Bergman blurted out in her acceptance speech that she thought Cortese would win -- and then later expressed her embarrassment that she had slighted the other three nominees in the category.) Day for Night is still one of Truffaut's most enjoyable movies, an account of the difficulties encountered by a director (played by Truffaut himself) in completing a studio-produced melodrama called Meet Pamela. He has to contend with an aging alcoholic actress (Cortese) who can't remember her lines so they have to be posted around the set, and who repeatedly opens the wrong door and walks into a closet during one of her big scenes. There is also a fragile leading lady (Jacqueline Bisset) who is returning to work after a nervous breakdown, an unexpectedly pregnant actress (Alexandra Stewart) in a key supporting role, an aging matinee idol star (Jean-Pierre Aumont), and a neurotic actor (Jean-Pierre Léaud) whose life is complicated by his romantic notions about women. Moreover, one of these performers will die before filming ends, making things even more difficult. That the film also bristles with insights into the filmmaking process only makes it a more durable addition to Truffaut's canon. For once, the English title, which refers to the technique of underexposing or filtering the images so that daytime shots appear to be taking place at night, is more suggestive than the French one (La Nuit Américaine is the French phrase for the same process) in evoking the illusion/reality paradox involved in making movies. One additional plus: Georges Delerue's wonderful score.

Thursday, March 10, 2016

Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976)

What everyone remembers about Network is its prescient look at the corruption of American television news. It's not just that the rantings of Howard Beale (Peter Finch) foreshadow the antics of Glenn Beck, Rush Limbaugh, and Bill O'Reilly, it's that where once TV news was in the hands of Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, trusted and avuncular, it's now dominated by Anderson Cooper and Megyn Kelly, glamorous and glib. But the chief problem is that recalling Network as a satire on television misses its real target: corporate capitalism. What we remember from the film is Beale's "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore," Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway in perhaps her best performance) reaching orgasm at the very thought of improving her network's ratings, and Diana and Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall) conspiring to assassinate Beale after his ratings decline. What we should remember is that Beale's ratings decline because he decides to tell his audiences what he perceives as the truth: that they've become mere pawns in a multinational drive to subsume individuality into corporate identity. The key scene in the film really belongs to Ned Beatty as Arthur Jensen, the head of the Communications Corporation of America, the conglomerate that owns the network and that Beale has disclosed is about to be taken over by a Saudi Arabian conglomerate. In the voice of God, Jensen tells Beale, "There is only one holistic system of systems, one vast and immanent, interwoven, interacting, multivariate, multinational dominion of dollars. Petro-dollars, electro-dollars, multi-dollars, reichmarks, yens, rubles, pounds, and shekels. It is the international system of currency which determines the totality of life on this planet. That is the natural order of things today." But when Beale tries to share this epiphany with his audience, they forsake him. In other words, remembering Network as a satire on television is to mistake the symptom -- the dumbing-down of journalism (and it applies as well to print as to electronic media) -- for the disease: the cancer of corporate greed. The screenplay by Paddy Chayefsky is partly at fault for making Howard Beale and Diana Christensen and the old-fashioned TV news executive Max Schumacher (William Holden) the central figures of the film instead of Jensen. It might have been partly remedied if Jensen had been played by a figure of equal charisma to Finch, Dunaway, and Holden, instead of by Beatty, a likable character actor best known for being violated by mountain men in Deliverance (John Boorman, 1972). (That said, Beatty delivers a terrific performance in his big scene, which deservedly earned him an Oscar nomination.) In the end, Network is really a kind of nihilist satire, not far removed in that regard from Dr. Strangelove (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) in its presentation of a world without alternatives or saviors. It's an entertaining film, with terrific performances, but a depressing one.

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

Marty (Delbert Mann, 1955)

It's been quite a few years since I last saw Marty and I had forgotten how engaging a movie it is. The credit largely belongs to Ernest Borgnine in the title role and Betsy Blair as Clara, touching in their vulnerability and remarkable low-key chemistry together. And of course there's Paddy Chayefsky's screenplay, which brings them together convincingly and keeps them apart smartly. I do have to object to Chayefsky's overdoing of the "what do you wanna do tonight" shtick, which kept contemporary comedians busy far too long, and to the self-pitying Italian mama stereotypes of Marty's mother, Mrs. Piletti (Esther Minciotti), and Aunt Catherine (Augusta Ciolli), but it's on the whole a well-made script. Some credit is obviously due to the director, Delbert Mann, who also directed Chayefsky's 1953 teleplay on which the movie is based. It was his big-screen debut and won him an Oscar, but he never followed up with another comparable film -- his best later work was probably on two Doris Day comedies, Lover Come Back (1961) and That Touch of Mink (1962). Oscars also went to Borgnine, Chayefsky, and the film itself, and nominations to Blair, Joe Mantell as Marty's pal Angie, Joseph LaShelle's wonderfully atmospheric cinematography, and to the art directors. In fact, if Marty has any lasting claim to fame other than being a satisfying romantic drama, it's in the Academy's uncharacteristic recognition of a "little" film -- especially noticeable in the mid-50s when the prevailing Hollywood trend was to "give 'em something they can't get on television." Since they had already gotten Marty on TV two years earlier, the Oscar attention was especially surprising. It didn't signal any sort of trend, however: The following year, the best picture winner was Around the World in 80 Days (Michael Anderson), a typically bloated extravaganza loaded with movie-star cameos, and for the first time, all of the best picture nominees for 1956 were filmed in color. It was as if the Academy had said, "Fine, we did our duty, now let's get back to business."

Tuesday, March 8, 2016

The Sin of Madelon Claudet (Edgar Selwyn, 1931)

|

| Lewis Stone and Helen Hayes in The Sin of Madelon Claudet |

*The others are Rita Moreno, Audrey Hepburn, and Whoopi Goldberg. Barbra Streisand and Liza Minnelli are sometimes included in the list, but Streisand's Tony and Minnelli's Grammy were honorary, not competitive, awards.

Monday, March 7, 2016

The Matchmaker (Joseph Anthony, 1958)

Like Lynn Riggs's Green Grow the Lilacs and Ferenc Molnár's Liliom, Thornton Wilder's play The Matchmaker is not performed much these days. The chief reason is probably that they were all made into hugely successful musicals: respectively, Oklahoma!, Carousel, and Hello, Dolly! And unlike George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion or William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, which weren't superseded by their musical incarnations My Fair Lady and West Side Story, they seem somewhat naked without their musical adornments. Still, the film version of The Matchmaker, made three years after the play became a Broadway success but six years before the musical smash, retains a great deal of charm. Much of it comes from its cast: Shirley Booth as Dolly Gallagher Levi, Paul Ford as Horace Vandergelder, Shirley MacLaine as Irene Molloy, Anthony Perkins as Cornelius Hackl, and in his first substantial screen role, an impish Robert Morse as Barnaby Tucker. Shorn of its musical trimmings, the movie depends largely on the farce-timing of the cast, who frequently break the fourth wall to talk directly to the audience. For some viewers, a little whimsy goes a long way, and The Matchmaker has an awful lot of it. Its "opening up" from the stage version by screenwriter John Michael Hayes sometimes feels forced, and the ending depends too heavily on an unconvincingly complete about-face by Vandergelder. But director Anthony, who did most of his work in the theater and had only one previous screen directing credit for The Rainmaker (1956), keeps things moving nicely.

Sunday, March 6, 2016

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (John Huston, 1972)

The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean belongs to a sub-genre that prevailed in the early 1970s; I think of them as "stoner Westerns." The huge success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969) spawned a lot of movies that took an irreverent look at the legend of the American Old West and were aimed at the younger countercultural audience. They include such diverse films as Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970), McCabe & Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971), The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (Philip Kaufman, 1972), Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973), and Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 1974). Most of them were seen as commentaries on American violence and the quagmire of the Vietnam War. Paul Newman, who had played Billy the Kid earlier in his career in The Left Handed Gun (Arthur Penn, 1958) as well as Butch Cassidy, found himself the go-to actor to portray Western legends: In addition to Judge Roy Bean, he was also cast as Buffalo Bill Cody in Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson (Robert Altman, 1976). The Life of Times of Judge Roy Bean began with an original screenplay by John Milius, who wanted to direct it and to star Warren Oates in the title role, but when Newman read the script, he arranged for the rights to be bought up and for John Huston to be brought on as director. There is a whiff of hommage to (or perhaps parody of) Butch Cassidy in the film: As in the earlier film, which has a musical interlude with Butch and Etta Place (Katherine Ross) larking around to the song "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head," Judge Roy Bean has a scene in which the Judge, Maria Elena (Victoria Principal), and a bear lark around to the song "Marmalade, Molasses & Honey," which was written for the film by Maurice Jarre, Marilyn Bergman, and Alan Bergman. The song earned an Oscar nomination, but Huston was unable to find a consistent tone for the movie, which lurches from broad comedy (much of it provided by antics with the bear) to satire (the triumph of an avaricious lawyer played by Roddy McDowall) to pathos (the death of Maria Elena). It is laced with cameos, some of which provide the film's highlights, particularly the over-the-top performances of Anthony Perkins as an itinerant preacher and Stacy Keach as an albino outlaw named Bad Bob. But Ava Gardner simply walks through her scene as Lillie Langtry -- a decided anticlimax, given that she's been the off-screen obsession of Bean through most of the film.

Saturday, March 5, 2016

Magic Mike XXL (Gregory Jacobs, 2015)

I liked Magic Mike (Steven Soderbergh, 2012). It was the work of a major Hollywood director with a charismatic performance by Matthew McConaughey and a well-turned plot, and it dealt with a subject, male strippers, that hadn't been done to death on screen. But the sequel has none of those things. McConaughey is missing, and although Soderbergh is credited as executive producer and (under his pseudonym "Peter Andrews") as cinematographer, the direction has been turned over to Gregory Jacobs, assistant director on many of Soderbergh's films. The screenplay by Reed Carolin, who wrote the earlier film, is long on incident but short on plot: There is little in the way of conflict or obstacles to build momentum for the story. It simply boils down to "the boys" -- an apt epithet for these middle-aged victims of Peter Pan syndrome -- trying to avoid the responsibility of career and family a little while longer. Instead of coming to terms with their problems, the film simply allows them to triumph at what they know they can't keep doing forever. Okay, yes, there is fun to be had here anyway: Channing Tatum, Matt Bomer, Joe Manganiello, and Adam Rodriguez are good-looking actors with a great deal of skill at flaunting their attributes. There are good contributions by Andie MacDowell as a lecherous aging Southern belle and especially by Jada Pinkett Smith as Rome, the proprietor of a private club where women can indulge their sexual fantasies. And what message the film has is a positive one: an affirmation of female sexual desire. It's not a bad movie, but just an unnecessary one.

Friday, March 4, 2016

Bell, Book and Candle (Richard Quine, 1958)

Kim Novak was an actress of very narrow range, but in the right role and with a good supporting cast, she made a strong, sexy impact, as she does in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955) and Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958). In Bell, Book and Candle, she is paired again with her Vertigo co-star, James Stewart, and surrounded by a supporting cast full of scene-stealers: Jack Lemmon, Elsa Lanchester, Hermione Gingold, and Ernie Kovacs. The movie is nothing special: a fantasy romantic comedy with Novak as Gillian Holroyd, a witch who runs a primitive-art gallery on the ground floor of the apartment house where Shep Henderson (Stewart), a book publisher, lives. She puts a spell on him; he leaves his fiancée, Merle Kittridge (Janice Rule), for her but breaks it off when he discovers that he's been hexed. And so on. The movie was made after Vertigo, and Novak and Stewart were re-teamed because of a deal Columbia had made when it loaned out Novak to Paramount for the Hitchcock film. It's not the most plausible of pairings: Novak was 25 to Stewart's 50 -- an age difference that was less problematic in the plot of Vertigo, with its theme of erotic obsession. Stewart chose never to play another romantic lead, but Bell, Book and Candle gives him some good moments to show off his exemplary skill at physical comedy, as in the scene in which he's forced to scarf down a nauseating witches' brew concocted by Mrs. De Passe (Gingold). The screenplay by Daniel Taradash opens up a one-set Broadway comedy by John Van Druten that had starred Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer. It was nominated for Oscars for art direction and for Jean Louis's costumes, but lost in both categories to Gigi (Vincente Minnelli). The cinematography is by James Wong Howe.

Thursday, March 3, 2016

The Southerner (Jean Renoir, 1945)

The Southerner is perhaps the best of the films Renoir made during his wartime exile in the United States, which is not to say that it ranks with his French masterpieces that include Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), or Rules of the Game (1939). It does, however, stand up well against the better American films of 1945, such as Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz), Spellbound (Alfred Hitchcock), or Leave Her to Heaven (John M. Stahl). It also earned him his only Oscar nomination as director: He lost to Billy Wilder for The Lost Weekend, but he was presented an honorary Oscar in 1975. The film was also nominated for sound (Jack Whitney) and music score (Werner Janssen). The Southerner feels less authentic than it might: Renoir was unable to overcome the Hollywood desire for gloss, so Betty Field looks awfully healthy and well-coiffed for the wife of a hard-scrabble cotton farmer whose family lives in a shack with no running water and whose youngest child almost dies of "spring sickness" -- a form of pellagra caused by malnutrition. Zachary Scott is a little more credible as her determined husband, Sam Tucker, a cotton picker who decides to start farming on his own. The role is a sharp contrast to his performance the same year in Mildred Pierce, in which he's a slick con man -- the kind of role he found himself playing more often. The cast also includes Beulah Bondi as Sam Tucker's grandmother, J. Carrol Naish as the Tuckers' stingy neighbor, and Norman Lloyd as the neighbor's nephew and man-of-all-work, who tries to drive the Tuckers off their land. Renoir is credited with the screenplay along with Hugo Butler, who did the adaptation of a novel by George Sessions Perry, but it was also worked on by an uncredited William Faulkner and Nunnally Johnson.

Wednesday, March 2, 2016

Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969)

Watching Costa-Gavras's great political thriller on a night when Donald Trump was raking in votes in the Republican primaries was unsettling. But then it was an unsettling film to watch in 1969, the year after Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated, the police clashed with demonstrators at the Democratic convention in Chicago, and Richard Nixon was elected president. What made it unsettling this time was the way the film shows the destructive collaboration of ideologues, buffoons, and thugs. It's a more grimly funny movie than I remembered, particularly in the portrayal of the general in charge of the police, who as played by Pierre Dux is both ideologue and buffoon. There is buffoonery also among the thugs, and Costa-Gavras has fun mocking the conspirators who, once they angrily leave the room in which they've been indicted, each try to open a locked door. But we mock them in vain. For while the efforts of the prosecutor played beautifully by Jean-Louis Trintignant are heroic and Costa-Gavras and screenwriter Jorge Semprún make us expect justice to prevail, it doesn't. The story is that of the assassination of Greek opposition politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963 and the subsequent investigation that brought a glimmer of hope to the country only to be squelched by the military coup of 1967. However, the film is set in no specific country -- it was filmed in Algeria -- and only an opening "disclaimer" that parodies the usual assertion about any resemblance to persons living or dead dares to say that the resemblances in the film are entirely intentional. Costa-Gavras and Semprún were political exiles from, respectively, Greece and Spain. The composer Mikis Theodorakis had been arrested and his music was banned in Greece; he gave Costa-Gavras permission to use existing compositions for the film score. But the decision to set the film in no particular place only strengthened its ability to reach out and make its story meaningful beyond a specific place and time. Although Yves Montand and Irene Papas get top billing as the assassinated politician and his wife, Montand's role is comparatively small and Papas's is virtually a cameo. The movie is mostly carried by Trintignant and by Jacques Perrin, one of its producers who also plays a very aggressive investigative journalist, and a capable supporting cast. It won Oscars as the best foreign-language film and for Françoise Bonnot's film editing. It was also the first film to be nominated in the best picture category, and picked up nominations for best director and best adapted screenplay, but lost in those categories to Midnight Cowboy and its director, John Schlesinger, and screenwriter, Waldo Salt.

Tuesday, March 1, 2016

Pride (Matthew Warchus, 2014)

The success of The Full Monty (Peter Cattaneo, 1997), a movie about unemployed steelworkers who become male strippers, seems to have inspired a new genre of feel-good movies about the struggles of the British working class. And Margaret Thatcher's union-breaking efforts during the 1984 coal-miners' strike has become the nexus for a series of films in the same spirit. The year before The Full Monty, there was Brassed Off (Mark Herman, 1996), about how the brass band staffed by unemployed coal miners helped raise spirits after their pit was closed. There was Billy Elliot (Stephen Daldry, 2000), about a striking miner's son who wants to become a ballet dancer. Like The Full Monty, it became a hit stage musical. Unfortunately, once you have a string of movies like these, you also have a formula to follow, which Stephen Beresford's screenplay for Pride, in which a group of gays and lesbians in London decide to raise funds to support striking Welsh miners, does almost to the letter. It's based on a true story, and the results are amusing and heart-warming, but a feeling of déjà vu works to prevent your feeling that you've seen anything fresh and surprising. What it has going for it is a beautifully committed cast, with some familiar old pros -- Bill Nighy, Imelda Staunton, Andrew Scott, and Dominic West -- and a few fine newcomers, particularly Ben Schnetzer, an American actor who launched his career in Britain. (An interesting reversal, considering the number of Brits, including West in The Wire and The Affair, along with Andrew Lincoln in The Walking Dead, Matthew Rhys in The Americans, and Hugh Dancy in Hannibal, who have found their careers flourishing in American television.) The film capitalizes on anti-Thatcher sentiments while downplaying the contemporaneous arrival of the AIDS crisis. There is a scene in which the group's leader, Mark Ashton (Schnetzer), encounters a former lover (a cameo by Russell Tovey) who is obviously ill, and a revelation that Jonathan Blake (West) was diagnosed with the disease several years earlier, but these are incidental to the main plot. The movie manages to avoid spoiling the feel-good mood by revealing only in the credits sequence that Ashton died at the age of 26 in 1987; Blake, however, is still alive.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_poster.jpg)