|

| Isabelle Huppert in La Truite |

Rambert: Jean-Pierre Cassel

Lou Rambert: Jeanne Moreau

Saint-Genis: Daniel Olbrychski

Galuchat: Jacques Spiesser

Daigo Hamada: Isao Yamagata

Verjon: Jean-Paul Roussillon

The Count: Roland Bertin

Mariline: Lisette Malidor

Carter: Craig Stevens

Party Guest: Ruggero Raimondi

Gloria: Alexis Smith

Director: Joseph Losey

Screenplay: Monique Lange, Joseph Losey

Based on a novel by Roger Vailland

Cinematography: Henri Alekan

Production design: Alexandre Trauner

Film editing: Marie Castro

Music: Richard Hartley

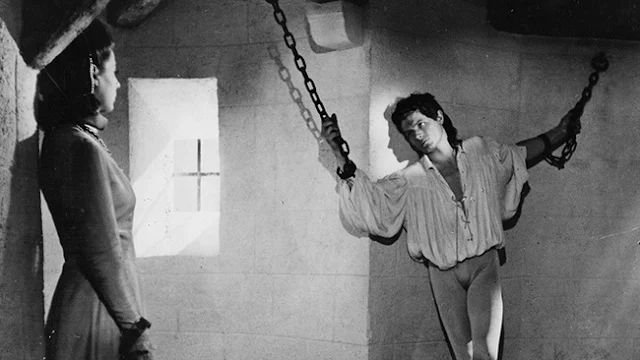

I wish I had known beforehand that Joseph Losey's La Truite is supposedly a comedy or a "French sex farce" as the description on Rotten Tomatoes puts it. I wouldn't have worried so much that I had lost my sense of humor -- or concluded that Losey didn't know how to tell a joke. Or perhaps I would have laughed more at the scenes that seem to be meant to be funny, like Frédérique's bowling-alley hustle or the one in which she tosses out of the window the taxidermied fish belonging to the man who molested her in adolescence. Or even at the absurdity of seeing such luminaries of French cinema as Isabelle Huppert, Jeanne Moreau, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in a bowling alley. There was one scene that amused me: Alexis Smith's very funny cameo appearance as the worldly wise Gloria, whom Frédérique, encumbered with an armload of gift-wrapped packages, encounters in a Japanese hotel. But there's really not much humor to be found in stale marriages, suicide attempts, sexual harassment, and an apparent murder, anyway. Mostly La Truite is a slog, with Losey unable to set the proper prevailing tone -- or really any tone -- for his story about a young woman's rise to power and influence. We spend so much time puzzling out who these characters are and what their relationships to one another may be, that there's not much time left to appreciate the story, especially since it's chopped up with flashbacks. We know where we are in time mostly by the length of Frédérique's hair, which starts out in her childhood in the trout hatchery as a waist-length red mane, has become a pageboy bob by the time she meets the Ramberts and Saint-Genis, and is chopped off becomingly when the latter takes her with him to Japan. La Truite is visually interesting, thanks to the work of two veterans of French film: cinematographer Henri Alekan and production designer Alexandre Trauner. But Losey's work as both director and screenwriter lets them, and his cast, down.