A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Monday, October 31, 2016

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar, 1989)

The vivid Technicolor imagination of Pedro Almodóvar doesn't serve him as well in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! as it did in his immediately previous hit film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988). This film feels rather like an uneasy mashup of a romantic comedy and a bondage porno. Actually, "porno" is too strong a word, for even though Tie Me Up! received an NC-17 rating on its release in the United States, there's very little in it that can't be seen any night on the mainstream shows of pay-cable outlets like HBO and Showtime. The most explicit scenes involve Marina (Victoria Abril) taking a bath with a mechanical tub toy shaped like a frogman that nuzzles into her private parts -- a scene that's more funny than erotic -- and an extended sex scene with Marina and Ricky (Antonio Banderas) that's undeniably erotic but not especially revealing -- it mainly shows their upper bodies, except for an overhead shot that reveals Banderas's posterior. What's more objectionable -- especially in the context of today's renewed dialogue about rape and sexual harassment in the context of the presidential campaign -- is the film's central plot premise: Ricky, who has just been released from a mental institution (whose director and nurses he has been happily bedding), kidnaps film star Marina, whom he once picked up and had sex with during an escape from the institution. In the course of trying to make Marina fall in love with him, Ricky keeps her tied up. Eventually, she finds herself falling in love with him, and the film ends with Ricky going off to live with her and her family. It can be argued that the premise is freighted with irony: Ricky's attempt to win Marina leads to his being severely beaten by the drug dealers he goes to see to procure something to relieve her toothache and other pains -- as a recovering drug addict, Marina finds almost any painkiller short of morphine ineffective. The kidnapper gets a measure of punishment for his misdeed, in other words. But the film's unsteady tone and the somewhat pat "happy ending" don't overcome the essentially distasteful sexual politics of the premise. Though it's a misfire, the movie gets good performances out of Banderas and Abril, as well as Loles León as Marina's exasperated sister, Lola, and Francisco Rabal as Marina's director, desperately trying to control the chaotic production of what may be his last film. The brightly colorful sets by production designer Esther Garcia, art director Ferran Sánchez, and set decorator Pepon Sigler, and the cinematography by José Luis Alcaine are also a plus.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

The Lavender Hill Mob (Charles Crichton, 1951)

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a golden age for British film comedy, and Alec Guinness was right at the heart of it with his roles in The Lavender Hill Mob, Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949), The Man in the White Suit (Alexander Mackendrick, 1951), The Captain's Paradise (Anthony Kimmins, 1953), and The Ladykillers (Mackendrick, 1955). It was the period when comic actors like Margaret Rutherford, Terry-Thomas, Alastair Sim, and the young Peter Sellers became stars, and British filmmakers found the funny side of the class system, economic stagnation, and postwar malaise. For it wasn't a golden age for Britain in other regards. Some of the gloom against which British comic writers and performers were fighting is on evidence in The Lavender Hill Mob, but it mostly lingers in the background. As the movie's robbers and cops career around London, we get glimpses of blackened masonry and vacant lots -- spaces created by bombing and still unfilled. The mad pursuit of millions of pounds by Holland (Guinness) and Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway) and their light-fingered employees Lackery (Sidney James) and Shorty (Alfie Bass) seems to have been inspired by the sheer tedium of muddling through the war and returning to the shriveled routine of the status quo afterward. Who can blame Holland for wanting to cash in after 20 years of supervising the untold wealth in gold from the refinery to the bank? "I was a potential millionaire," he says, "yet I had to be satisfied with eight pounds, fifteen shillings, less deductions." As for Pendlebury, an artist lurks inside the man who spends his time making souvenir statues of the Eiffel Tower for tourists affluent enough to vacation in Paris. "I propagate British cultural depravity," he says with a sigh. Screenwriter T.E.B. Clarke taps into the deep longing of Brits stifled by good manners -- even the thieves Lackery and Shorty are always polite -- and starved by the postwar rationing of the Age of Austerity. Clarke and director Charles Crichton of course can't do anything so radical as let the Lavender Hill Mob get away with it, but they come right up to the edge of anarchy by portraying the London police as only a little more competent than the Keystone Kops. The film earned Clarke an Oscar, and Guinness got his first nomination.

Saturday, October 29, 2016

Oldboy (Park Chan-wook, 2003)

It's about as improbable a premise for a thriller you'll find: A man, out on a drunken spree, wakes up imprisoned in what looks like a cheap hotel room where he stays, not knowing who put him there or why, for 15 years. His only contact with the outside world is a television set; his food is slipped to him through a slot in the door, and occasionally gas that puts him to sleep is pumped in the room so that it can be cleaned while he is unconscious. Then one day he is suddenly released and provided with cash and a cell phone. He begins to hunt compulsively for answers about who has done this to him. It's a mad plot, riffing on themes of guilt and obsession that are worthy of Kafka or Dostoevsky, but instead are cast in the idiom of horror movies and martial arts films. Eventually, the protagonist, Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), will find the answers to what he seeks, but the truth will be more shattering than satisfying. Oldboy won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Festival, and no one who knows movies will be surprised to find that the jury was presided over by Quentin Tarentino, who gets the same inspiration from violent pop culture that Park Chan-wook demonstrates. The screenplay for Oldboy, on which Park shares credit with Lim Chun-hyeong and Hwang Jo-yun, was based on a Japanese manga. Park has said that he named his protagonist Oh Dae-su as a near homonym for Oedipus, who shared a similar fate when he discovered the truth, but Oldboy is closer to Saw (James Wan, 2004) than to Sophocles. Nevertheless, Oldboy has provocative things to say about guilt and revenge, and Choi's performance as the abused and haunted Dae-su is superb. Yu Ji-tae is suavely menacing as the villain, and Kang Hye-jeong is touching as Mi-do, who aids Dae-su in his quest. The often startlingly grungy production design is by Ryu Seong-hie and the cinematography by Chung Chung-hoon. There is a stunningly accomplished long take in the middle of the film in which the camera follows Dae-su as he single-handedly battles an army of opponents in a hallway that stretches across the wide screen like a frieze on the entablature of a temple. For once, however, a tour-de-force display of cinema technique doesn't overwhelm the rest of the film.

Friday, October 28, 2016

Young Frankenstein (Mel Brooks, 1974)

No telling how many times I've seen this blissful comedy, but I always find something new in it. This time, I was struck by Mel Brooks's musicality. There's the great "Puttin' on the Ritz" number, obviously, and Madeline Kahn bursting into an orgasm-induced rendition of "Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life" as Jeanette MacDonald never sang it. But the score by John Morris is wonderful on its own, as in the serenade to the monster on violin and horn played by Frederick (Gene Wilder) and Igor (Marty Feldman). And even the gag references sing: Frederick's appropriation of Mack Gordon's lyrics to "Chattanooga Choo Choo" when he arrives at the Transylvania (get it?) Station, or the supposedly virginal Elizabeth (Kahn) singing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." It's also surprising how little really smutty humor Brooks indulges in this time. There's Inga's (Teri Garr) appreciation of the monster's "enormous schwanzstucker," to be sure, but this is PG humor at worst. So many of the gags are just wittily anti-climactic, like Frau Blucher (Cloris Leachman) proclaiming that Victor Frankenstein "vas my ... boyfriend!" Or the Blind Man (Gene Hackman) wistfully calling out to the fleeing monster, "I was gonna make espresso." (Hackman ad-libbed this line, and many other gags in the film, such as Igor's movable hump, were improvised by the actors.) And has a spoof ever been so beautifully staged? The production design is by Dale Hennesy, who had the wit to track down and borrow the original sparking and buzzing laboratory equipment that Kenneth Strickfaden created for the first Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931). The equally evocative black-and-white cinematography is by Gerald Hirschfeld.

Thursday, October 27, 2016

Spectre (Sam Mendes, 2015)

How can there be, by current count, 24 James Bond films? (Not counting the 1967 spoof version of Casino Royale, which had no fewer than five directors, including John Huston.) Why has the series not run its course by now? It has survived regular cast changes, including its central character, who has been played by six different actors: The current Bond, Daniel Craig, had not even been born when the first film in the series, Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962), premiered. Even recurring characters have been recast: M, Miss Moneypenny, and Q have each been played by five actors, and M underwent a change from male to female when Judi Dench took over the role in GoldenEye (Martin Campbell, 1995), though the part reverted to male (Ralph Fiennes) at the end of Skyfall (Sam Mendes, 2012). Yet the series has retained a reassuring familiarity, even to the point of typically beginning with a spectacular action sequence that almost certainly can't be topped in the remaining parts of the film. In Spectre, Bond is in Mexico City, where he shoots a bad guy, setting off an explosion that has him scrambling to escape from the building's collapsing façade, then chases another bad guy escaping from the rubble onto a helicopter, on which they struggle for control as it careens wildly over the crowds celebrating the Day of the Dead in the Zócalo. Then come the credits and another Bond-film staple, the thematic pop song: This one, "Writing's on the Wall," sung by Sam Smith, who co-wrote it with Jimmy Napes, won an Oscar. And then it's down to the usual business: chastisement by M (Fiennes), gadgets by Q (Ben Whishaw), and pursuit of the villains seeking control of the world. In Spectre there are two: One, Max Denbigh (Andrew Scott), is trying to take over control of intelligence services all over the world, while the other is a familiar figure from earlier Bond films, Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz), who is in cahoots with Denbigh. (Blofeld, who had been a regular supervillain in the Sean Connery era, was absent from the Bond films after 1983 because of copyright litigation that was settled before Spectre, which takes its title from Blofeld's global criminal organization, was filmed.) There are also vodka martinis, shaken not stirred, to be quaffed, and "Bond girls" to be bedded -- although in recent years, Bond's sex life has become less wildly promiscuous and the women have become more complex characters. In Spectre, one of them, Madeleine Swann, is played by Léa Seydoux, a more than capable actress who sometimes seems to be fighting against the limitations of the role, trying to make Madeleine a more interesting figure than the screenplay allows. So to return to the original question: Why do we still gravitate to the Bond films when there are more novel action-adventures to be had? The series has been so frequently imitated -- Tom Cruise's Mission: Impossible movies are virtually indistinguishable in formula from Bond films -- that maybe imitation suggests the answer: We crave the familiar, but we also relish the small surprises when the formula is tweaked. In Spectre, for example, M, Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), and Q all get out of the office and into the field for a change. Spectre is not quite as satisfying an outing as Skyfall, and there are signs of fatigue in Craig's performance, suggesting that his term as Bond has run its course -- though he has reportedly signed on for the next one. But longevity can be its own reward: We have become so comfortable with the formula that it still excites people to speculate about the next James Bond -- Tom Hiddleston? Idris Elba?

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

21 Grams (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2003)

|

| Melissa Leo and Benicio Del Toro in 21 Grams |

Cristina Peck: Naomi Watts

Jack Jordan: Benicio Del Toro

Mary Rivers: Charlotte Gainsbourg

Michael: Danny Huston

Marianne Jordan: Melissa Leo

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Screenplay: Guillermo Arriaga

Cinematography: Rodrigo Prieto

Music: Gustavo Santaolalla

An egg is an egg no matter how you scramble it. You can whip it into a meringue or a soufflé or an omelet, but it still retains its eggness. The same thing, I think, is true of melodrama: There's no disguising its improbabilities and coincidences, its short cuts around motive and characterization, its intent to surprise and shock. Mind you, I don't have anything against melodrama. Some of my favorite films are melodramas, just as some of our greatest plays, even some of Shakespeare's tragedies, are grounded on melodrama. It's just that you have to approach it without pretension, which is, I think, the chief failing of Alejandro González Iñárritu's 21 Grams. The melodramatic premise is this: The recipient of a heart transplant falls in love with the donor's widow, who then persuades him to try to kill the man who killed her husband. It's the stuff of which film noir was made, but Iñárritu takes screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga's premise and scrambles it, using non-linear narrative devices -- flashbacks and flashforwards -- and casting an unrelievedly dark tone over it, as well as reinforcing a pseudoscientific message in the title, which is explicated at the end of the film. In 1907, a Massachusetts physician named Duncan MacDougall tried to weigh the human soul: He devised a sort of death-bed scales, which would register any loss of weight at the moment a patient died, thereby demonstrating to his satisfaction -- if not to the medical and scientific communities -- that the weight of the soul was approximately three-quarters of an ounce, or 21 grams. I suspect that Arriaga and Iñárritu meant the allusion to this bit of nonsense metaphorically, but it doesn't come off that way. By the end of the film, we are so weighed down with the misery of its protagonists that it feels like sheer bathos. This is not to say that 21 Grams is a total loss as a film. Iñarritu is one of our most celebrated contemporary directors, with back-to-back Oscars for Birdman (2014) and The Revenant (2015) to prove it. I just don't think he's found himself yet, but has become too caught up in narrative gimmicks that prevent him from delivering a completely satisfying film. There is much in 21 Grams to admire: The performances of Sean Penn, Naomi Watts, Benicio Del Toro, and Melissa Leo are as fine as their reputations suggest they would be. The narrative tricks are done with great skill, especially with the aid of cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, who uses color to make each of the narrative segments distinct from the others, so that when the film cuts from one to another, the viewer feels better oriented. And there's no denying the emotional impact of the film as a whole. It could hardly be otherwise, given the pain suffered by the protagonists: Cristina, who lost her husband and her two little girls; Jack, the ex-con who accidentally killed them and believes that it was all because Jesus wanted it to happen; and Paul, who finds his chance at a new life marred by knowledge that it was at the expense of other people's happiness. But in the end, all of this suffering is off-loaded onto us without any compensatory feeling of having been enlightened by it.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976)

Even 40 years later, In the Realm of the Senses still has the power to shock, and not just because of the full nudity and unsimulated copulation -- we've all seen pornography in some form. It's that we've never seen them used in service of story, characterization, and theme as well as they are in this film. It's based on an actual incident that took place in Japan in 1936: Sada Abe killed her lover, Kichizo Ishida, during an experiment in erotic asphyxiation, then cut off his genitals and carried them with her for three days until she was arrested. Fascinated by this story, and by producer Anatole Dauman's suggestion that they should make a pornographic film, Oshima wrote the screenplay and set about putting together a cast and crew. The lead actors, Tatsuya Fuji as Kichizo and Eiko Matsuda as Sada, are extraordinary, transcending the mere shock value of their physical encounters with their commitment to illuminating the motives and the inner life of the couple. They give as complete a portrait of sexual obsession as we're ever likely to encounter in a movie. Oshima doesn't skimp on portraying the excesses of their passion: Sada persuades Kichizo to have sex with the 68-year-old geisha who comes to serenade them -- he is somewhat disgusted, but she is aroused when he does. The maids who tend to their room complain that it smells -- "We like it that way," Sada replies -- and the older man with whom Sada has been having sex to get money to support the lovers ends their relationship by saying she smells somewhat like a dead rat. But Oshima also portrays them as symbolic rebels against the militarism of 1930s Japan -- making love not war, if you will -- in a scene in which Kichizo, returning to Sada, passes marching troops being cheered by flag-waving schoolchildren. The real Sada was tried for his murder and mutilation, but served only five years in prison and became something of a folk legend in Japan, living on until the 1970s. A French and Japanese co-production, In the Realm of the Senses was filmed in Japan, but the footage had to be developed in France to avoid prosecution, and it has never been released in Japan without cuts or strategic blurring of its sex scenes. The movie is often quite beautiful, with cinematography by Hideo Ito and sets by Shigemasa Toda, but it's certainly not a film for all viewers.

Monday, October 24, 2016

My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava, 1936)

I don't know if director Gregory La Cava and screenwriters Morrie Ryskind and Eric Hatch intentionally set out to subvert the paradigm of the romantic screwball comedy in My Man Godfrey, but they did. It has all the familiar elements of the genre: the "meet-cute," the fallings-in and fallings-out, and the eventual happily-ever-after ending. And it is certainly one of the funniest members of the genre. William Powell is his usual suave and sophisticated self, and nobody except Lucille Ball ever played the beautiful nitwit better than Carole Lombard. But are Godfrey (Powell) and Irene (Lombard) really made for each other? Isn't there something really amiss at the ending, when Irene all but railroads Godfrey into marriage? Knowing that marriage is an inevitability in the genre, I kept wanting Godfrey to pair off with Molly (Jean Dixon), the wisecracking housemaid who conceals her love for him. And even Cornelia (Gail Patrick), the shrew Godfrey has tamed, seems like a better fit in the long run than Irene, with her fake faints and tears. The film gives us no hint that Irene has grown up enough to deserve Godfrey. Or is that asking too much of a film obviously derived from the formula? Perhaps it's just better to take it for what it is, and to enjoy the wonderful performances by Alice Brady, Eugene Pallette, Alan Mowbray, and Mischa Auer, and the always-welcome Franklin Pangborn doing his usual fussy, exasperated bit. A lot could be written, and probably has been, about how the film reflects the slow emergence from the Depression, with its scavenger-hunting socialites looking for a "forgotten man." a figure that only three years earlier, in Gold Diggers of 1933 (Mervyn LeRoy), had been treated with something like reverence in the production number "Remember My Forgotten Man." Had sensibilities been so hardened over time that the victims of the Depression could be treated so lightly? In any case, My Man Godfrey was a big hit, and was the first movie to have Oscar nominations -- for Powell, Lombard, Auer, and Brady -- in all four acting categories. It was also nominated for director and screenplay, though not for best picture.

Sunday, October 23, 2016

Kagemusha (Akira Kurosawa, 1980)

In the climactic moments of Kagemusha director Akira Kurosawa does something I don't recall seeing in any other war movie: He shows the general, Katsuyori (Ken'ichi Hagiwara) sending wave after wave of troops, first cavalry, then infantry, against the enemy, whose soldiers are concealed behind a wooden palisade, from which they can safely fire upon Katsuyori's troops. It's a suicidal attack, reminiscent of the charge of the Light Brigade, but Kurosawa chooses not to show the troops falling before the gunfire. Instead, he waits until after the battle is over and Katsuyori has lost, then pans across the fields of death to show the devastation, including some of the fallen horses struggling to get up. It's an enormously effective moment, suggestive of the dire cost of war. The film's title has been variously interpreted as "shadow warrior," "double," or decoy." In this case, he's a thief who bears a remarkable resemblance to the formidable warlord Takeda Shingen and is saved from being executed when he agrees to pretend to be Shingen. (Tatsuya Nakadai plays both roles.) This masquerade is designed to convince Shingen's enemies that he is still alive, even though Shingen dies soon after the kagemusha agrees to the ruse. The impostor proves to be surprisingly effective in the part, fooling Shingen's mistresses and winning the love of his grandson, and eventually presiding over the defeat of his enemies. But he gains the enmity of Shingen's son, Katsuyori, who not only resents seeing a thief playing his father but also holds a grudge against Shingen for having disinherited him in favor of the grandson. So when the kagemusha is exposed as a fake to the household, he is expelled from it, and Katsuyori's arrogance leads to the defeat in the Battle of Nagashino -- a historical event that took place in 1575. The poignancy of the fall of Shingen's house is reinforced at the film's end, when his kagemusha reappears in rags on the bloody battlefield, then makes a one-man charge at the palisade and is gunned down. The narrative is often a little slow but the film is pictorially superb: Yoshiro Muraki was nominated for an Oscar for art direction, although many of his designs are based on Kurosawa's own drawings and paintings, made while he was trying to arrange funding for the film. Two American admirers, Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, finally came through with the financial support Kurosawa needed -- they're listed as executive producers of the international version of the film, having persuaded 20th Century Fox to handle the international distribution.

Saturday, October 22, 2016

Intolerance (D.W. Griffith, 1916)

|

| The Belshazzar's Feast set for Intolerance |

|

| Edwin Long, The Babylonian Marriage Market, 1875. |

Friday, October 21, 2016

Love & Friendship (Whit Stillman, 2016)

Jane Austen's greatest novels -- by which I mean Emma, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion -- do tend to run to formula. The heroines are all marriageable young women who for one reason or another are having trouble finding a mate. They are usually put in jeopardy of marrying scoundrels -- Emma to Frank Churchill, Elizabeth Bennet to Mr. Wickham, Fanny Price to Henry Crawford -- or fools -- Emma to Mr. Elton, Elizabeth to Mr. Collins -- or in Anne Elliot's case not at all, a calamitous fate in the world of the novels. Eventually, however, they find their Mr. Knightley or Darcy or Edmund or Capt. Wentworth and live happily ever after. The pattern is so familiar that it persists to this day in romance novels, but it's not why we read Jane Austen. We read her for the wit, the moral observations, the deft interplay of personalities, which is why even the best movies made from her books are slightly unsatisfying: Film can't do justice to what's on the page. And that's why I think Love & Friendship may be the best Jane Austen movie ever: What's on the page in its source, Lady Susan, the epistolary novella she never submitted to a publisher, departs radically from the formula. The titular heroine (played brilliantly in the film by Kate Beckinsale) is herself the scoundrel, more in the mold of Henry Crawford's sister, Mary, in Mansfield Park than any of Austen's more familiar heroines. And she winds up marrying the fool, the wealthy Sir James Martin (Tom Bennett), whom she originally planned as a husband for her daughter, Frederica (Morfydd Clark), after having courted Reginald DeCourcy (Xavier Samuel), who winds up marrying Frederica. Whit Stillman's screenplay is a brilliant transformation of what's on the pages of the source, where the point of view is limited to that of the letter writers. The freedom to manipulate point of view in the film allows him to play with inverting the formula: In the film, Reginald takes on the role usually played by Austen's heroines, i.e., almost marrying the scoundrel. With Bennett's considerable help, Stillman makes Sir James Martin into one of the funniest fools ever, so blithely out of it that he is astonished to learn that Frederica reads "both verse and poetry" and thinks that Moses delivered 12 commandments -- after being told that there are only ten, he tries to decide which two he should discard. He also winds up after his marriage to Lady Susan in a ménage à trois that includes Lord Manwaring (Lochlann O'Mearáin), but he remains apparently unaware that Manwaring is her real lover and the father of the child she is carrying. That last could never have found its way into print in Austen's day, of course, but Stillman succeeds in integrating it into a convincingly Austenian context. The performers, which also include Chloë Sevigny, Jemma Redgrave, James Fleet, and in a cameo role, Stephen Fry, are uniformly fine. If there is a flaw to the film, it may be that it's "rather too light, and bright, and sparkling," which is the criticism that Austen made of Pride and Prejudice. But if it sometimes feels like a parody of a Jane Austen novel, it's a masterly one.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

Hail the Conquering Hero (Preston Sturges, 1944)

What sort of nerve must it have taken to make a film that pokes fun at patriotism, mother love, small towns, political campaigns, and the Marines in the middle of World War II? Preston Sturges's film begins in a small nightclub, where a singer (Julie Gibson) and her backup group of singing waiters launch into a stickily sentimental song, "Home to the Arms of Mother" (music and lyrics by Sturges), whereupon John F. Seitz's camera begins a traveling shot from the group and down a long bar at the end of which we see Woodrow Lafayette Pershing Truesmith (Eddie Bracken) drowning his sorrows. When a group of six Marines on leave after having fought at Guadalcanal enters the bar, Woodrow buys a round for them, and is prodded into telling them his sad story: He joined the Marines, trying to follow in the footsteps of his father, a Marine who died in World War I, but was discharged because of chronic hay fever. But instead of returning home to the arms of mother, he went to work in a shipyard and arranged for a friend to send his letters to her from overseas, disguising the fact that he was no longer a Marine. One of the men, Sgt. Heppelfinger (William Demarest), learns that Woodrow's father was his old buddy who fought with him at Belleau Wood, while another, Bugsy (Freddie Steele), is appalled that Woodrow hasn't been home to see his mother since the start of the war. So the Marines collude to take an extremely reluctant Woodrow back to his hometown and pretend that he's a war hero who has just been discharged. Naturally, the plan backfires spectacularly when the whole town joins in the celebration and even railroads Woodrow into running against the corrupt mayor (Raymond Walburn). Speed is of the essence in a farce like this, because if anyone ever gave Woodrow a moment to talk, the whole thing would collapse like a soufflé. On the other hand, too much fast talk can be wearying, so Sturges introduces a romantic subplot: Feeling that he can never return home, Woodrow has written his girlfriend, Libby (Ella Raines), that he has met someone else, so Libby has gone and got herself engaged to Forrest Noble (Bill Edwards), the son of the town's corrupt mayor. To slow the pace down, Sturges introduces a long walk-and-talk tracking scene in which Libby, confused by her revived feelings for Woodrow, tries to sort things out with Forrest, but to no avail. It's a funny, beautifully written scene, but it doesn't quite work because neither Raines nor Edwards is up to the acting demands it puts on them -- I kept thinking how much better Joel McCrea and Claudette Colbert or Henry Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck would have played it. Bracken, however, is wonderful, as are Demarest, Steele, Walburn, and other members of Sturges's usual crew of brilliant character actors, including Franklin Pangborn as the harried planner of the celebration and Jimmy Conlin as the town judge. This was, sadly, the last film Sturges made under his Paramount contract, which he ended because of studio interference during the making of the movie. It objected, perhaps rightly, to Ella Raines's lack of star power, but also took the film out of Sturges's hands and edited it. After a couple of disastrous previews of the studio version, however, Sturges was called back in for rewrites and some new scenes. The revised Sturges version was a hit, and earned him an Oscar nomination for best screenplay.

Wednesday, October 19, 2016

Belle de Jour (Luis Buñuel, 1967)

Belle de Jour is a famously enigmatic film, venturing into (and often blurring) the space between reality and fantasy, between waking life and dreams. It has led a lot of people astray, into questions like: What's buzzing in the Asian client's box that so frightens the other prostitutes in the brothel, but so satisfies Séverine (Catherine Deneuve)? Why does Séverine so often hear cats meowing? What is the Duke (Georges Marchal) doing that so shakes the coffin in which he has posed Séverine and causes her to flee into the rain? Why is Pierre (Jean Sorel) so fascinated by the wheelchair that foreshadows his fate? How much of any of this is meant to be reality? Critics have been more or less preoccupied by these and other matters of speculation and interpretation for almost 50 years. But I, for one, am content to invoke Keats's "negative capability," which he defined as the ability of an artist to be "in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." Of course, it would be abrogating the critics' responsibility if they failed to pursue the aesthetic and moral effects of the enigmas introduced into the film by Luis Buñuel and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière. I'm arguing that their effect is collective and cumulative, that pursuing any one of these details in search of a definitive answer is like concentrating on the threads at the expense of seeing the tapestry. Belle de Jour is subject to all forms of analysis -- Freudian, Jungian, Lacanian, Marxist, feminist, you name it -- but without exhausting its possibilities to tantalize. I think Buñuel's major achievement in the film is in sticking to his roots in surrealism without resorting to surrealist clichés: Every scene, even the obvious fantasies like the one in which Séverine is pelted with muck by Pierre and Husson (Michel Piccoli), is grounded in actuality, down to the specific address and the mundane Parisian location given to the brothel run by Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page). It's only in reflecting on the film that we begin to question which scenes are "real" and which aren't. Belle de Jour is one of those inexhaustible films that you revisit with the certain knowledge that it will look slightly different to you every time.

Tuesday, October 18, 2016

Madame de... (Max Ophuls, 1953)

The word "tone" is much bandied about by critics, myself included. We speak of a film as being "inconsistent in tone" or its "melancholy, despairing tone" or its "shifts in tone." But ask us -- or, anyway, me -- what we mean by the term, and you may get a lot of stammering and hesitation. Even my old copy of the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics falls back on calling it "an intangible quality ... like a mood in a human being." So when I say that Madame de... is a masterwork in its manipulation of tone, you have to take that observation as a kind of awestruck, slightly inarticulate response to a film that begins in farce and ends in tragedy. The American title of the film was The Earrings of Madame de..., but to my mind that puts the emphasis on what is, in effect, merely a MacGuffin. The earrings were given to Countess Louise de... (Danielle Darrieux) by her husband, General André de... (Charles Boyer), on their wedding day. (Their full surname is coyly hidden throughout the film: A sound blots out the latter part of the name when it is spoken, and it is hidden by a flower when it appears on a place card at a banquet. The effect is rather like a newspaper gossip column trying to avoid a libel suit when reporting a scandal among the aristocracy.) The scandal is set in motion when Louise, a flirtatious woman with many admirers, decides to sell the earrings to pay off the debts she wants to hide from André. Their marriage has obviously come to a pause: Though they remain affectionate with each other, they have separate bedrooms and at night they talk to each other through doors that open on a connecting room. Louise takes the earrings to the jeweler (Jean Debucourt) from whom André originally purchased them. But when she tries to persuade André that she lost them at the opera and the "theft" is reported in the newspapers, the jeweler tries to sell them back to the general. To put an end to the business, André pays for them, then presents them to his mistress, Lola (Lia Di Leo), as a parting gift: Their affair over, she is leaving for Constantinople. There, Lola gambles them away, but they are bought by an Italian diplomat, Baron Donati (Vittorio De Sica), who is on his way to a posting in Paris. And of course Donati meets Louise, they fall in love, and he presents the earrings to her as a gift. Recognizing them, she has no recourse but to hide them, but they will resurface with fatal results. How Max Ophuls gradually shades this plot from a situation suited to a Feydeau farce into a poignant conclusion is a part of the film's magic. It depends to a great extent on the superb performances of Darrieux, Boyer, and De Sica, but also on Ophuls's typically restless camera, handled -- as in Ophuls's La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952), and Lola Montès (1955) -- by cinematographer Christian Matras, as it explores Jean d'Eaubonne's elegant fin de siècle sets. Much depends, too, on the film editor, Borys Lewin, who helps Ophuls accomplish one of the movies' great tours de force, following Louise and Donati as they dance what appears to be an extended waltz but gradually shows itself to be several waltzes taking place over the period of time in which they fall in love. It's a cinematic showpiece, but it's fully integrated into what has to be one of the great movies.

Monday, October 17, 2016

Dukhtar (Afia Nathaniel, 2014)

Sunday, October 16, 2016

Easy Living (Mitchell Leisen, 1937)

Easy Living is one of my favorite screwball comedies, but I once had a nightmare that took place in the set designed by Hans Dreier and Ernst Fegté for the film. It was the luxury suite in the Hotel Louis, with its amazingly improbable bathtub/fountain, and I dreamed that we had just bought a place that looked like it and were moving in. I don't remember much else, other than that I was terribly anxious about how we were going to pay for it. Most of my dreams are anxiety dreams, I think, which may be why I love screwball comedies so much: They take our anxieties about money and love and work, like Mary Smith (Jean Arthur) worrying about how she's going to pay the rent and even eat now that she's lost her job, and transform them into dilemmas with comic resolutions. Too bad life isn't like that, we say, but with maybe a kind of glimmer of hope that it will turn out that way after all. Easy Living, with its screenplay by Preston Sturges, is one of the funniest screwball comedies, but it's also, under Mitchell Leisen's direction, one of the most hilarious slapstick comedies. How can you not love a film in which a Wall Street fat cat (Edward Arnold) falls downstairs? Or the celebrated scene in which the little doors in the Automat go haywire, producing food-fight chaos that builds and builds? The fall of the fat cat and the rush on the Automat reveal that Easy Living was a product of the Depression, anxiety made pervasive and world-wide, when we needed hope in the form of comic nonsense to keep us going. This is also an essential film for those of us who love Preston Sturges's movies, for although he didn't direct it, his hand is evident throughout, not only in the dialogue but also in the casting, with character actors who would later form part of Sturges's stock company, Franklin Pangborn, William Demarest, and Robert Greig among them. Ray Milland displays a Cary Grant-like glint of amusement at what's going on, Luis Alberni spouts Sturges's wonderful malapropisms as the hotel owner Louis Louis, and Mary Nash brings the right amount of indignation and humor to her role as Arnold's wife. I only wonder why Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin weren't credited for their title song, which is heard (though without its lyrics), as background music throughout the film.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

Fugitive Pieces (Jeremy Podeswa, 2007)

I dislike the phrase "Holocaust film," which often gets used with a hint of condescension, suggesting that there is a genre of film that plays on our established feelings of grief and indignation about a terrible passage in history. It seems to imply that filmmakers who tell stories about the Holocaust and its effects are working with a subject that disarms criticism: that if it's about the Holocaust, a film doesn't have to worry about winning over an audience. That attitude ignores, for example, the controversy that surrounded Roberto Benigni's Life Is Beautiful (1997), which was both celebrated and condemned. The enormity of the Holocaust tends to overwhelm conventional cinematic narrative, so that the best films in which it forms the background are those that focus on the experiences of actual people like Oskar Schindler in Schindler's List (Steven Spielberg, 1993) and Wladyslaw Szpilman in The Pianist (Roman Polanski, 2002), or thinly fictionalized accounts drawn from personal experience, like Louis Malle's in Au Revoir les Enfants (1987). Jeremy Podeswa's Fugitive Pieces, adapted by the director from a novel by Anne Michaels, is one of those films that are almost swamped by the historical actuality of the Holocaust; it takes as its subject the experience of "survivor guilt." Its fictional protagonist, Jakob Beer (played as a child by Robbie Kay and as a man by Stephen Dillane), escapes from the Nazis but loses his family. He is rescued by Athos Roussos (Rade Serbedzija), a Greek archaeologist who was working in Poland on a dig and discovered Jakob hiding in the woods. Somehow -- the film is unclear on exactly how -- Athos smuggles Jakob out of Poland to his home in Greece, and after the war the two emigrate to Canada, where Athos has been invited to teach. Jakob grows up haunted by his childhood trauma, and his first marriage, to a woman named Alex (Rosamund Pike), ends when she reads his journals and discovers what a barrier Jakob's experiences have created between them. Jakob is particularly tormented by the loss of his sister, Bella (Nina Dobrev), a talented musician, who often appears in his dreams. Even after publishing a book about his life, Jakob doesn't fully overcome the past until after the death of Athos, whose wisdom he comes to appreciate with the help of another woman, Michaela (Ayelet Zurer). There is a subplot involving the Jewish couple across the hall from Athos and Jakob in Canada, whose son, Ben (Ed Stoppard), grows up hating his father, a Holocaust survivor, for his harshness: The father, for example, berates Ben for not finishing the apple he has been eating, reminding him how grateful people in the camps would have been for the food. Despite excellent performances from everyone, the film sinks too often into sentimentality and stereotypes: Serbedzija's performance is a standout, but he can't overcome the fact that Athos, though a university professor, is presented as too much the wise and kindly peasant-sage, preaching the value of ties to the earth. There are some major gaps in the narrative, like the journey from Poland to Greece, and some overall shapelessness, and the ending is much too pat.

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935)

Funny, campy, occasionally scary, and featuring over-the-top performances by Ernest Thesiger, Dwight Frye, and Una O'Connor, Bride of Frankenstein may also be the saddest of all horror movies. Much has been made of a perceived subtext of the film, based in part on the knowledge that its director, James Whale, and Thesiger were openly gay, and it's possible to see the plight of the monster (Boris Karloff) as analogous to that of the gays of their time, subject to ridicule and repression from a hostile society. In this reading, Whale and Thesiger adopt camp attitudes as a way of thumbing their noses at a hostile, uncomprehending society. But that's an unnecessarily reductive interpretation. The monster is the ultimate outsider, an anomalous and inarticulate being, whatever his sexuality. He briefly finds companionship in the blind hermit (O.P. Heggie) who begins to teach him to speak -- including the word "friend" -- but their relationship is doomed by the intrusion of the world of ordinary humans, a world he can never be part of. In the end, when the mate (Elsa Lanchester) who has been created for him rejects him, his only recourse is self-destruction. "We belong dead!" the monster proclaims. To see Bride of Frankenstein as some sort of parable about gays in society would then be an endorsement of suicide as the only option. Subtexts often reside only in the mind of the beholder, and Whale was too much of an artist to turn his film into any kind of message, however latent in the fantastic tale he is telling. Better instead to relish Karloff's ability to give a subtle performance that shows through pounds of makeup. Or Lanchester's remarkable control and timing in bringing the bride to life, including the squawks and hisses that she claimed to have developed by watching swans in the park. Or John J. Mescall's classic black-and-white cinematography, Charles D. Hall's set designs, and Franz Waxman's score. Yes, Colin Clive and Valerie Hobson are a most improbable couple as the Frankensteins. Clive was far gone into alcoholism and looks it, but nobody could have delivered the line "She's alive! Alive!" more memorably.

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Au Revoir les Enfants (Louis Malle, 1987)

|

| Raphael Fejtö and Gaspard Manesse in Au Revoir les Enfants |

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Brooklyn (John Crowley, 2015)

This story about an Irish girl's coming of age has the strong whiff of traditional movie storytelling about it. And that's what makes it so entirely satisfying: It fulfills the need we often feel to be reassured about the stability of familiar things. But it also serves to support its theme, which is that nostalgia can be a trap, or to put it in a phrase that has become a cliché: You can't go home again. Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan) feels stifled in her small Irish town, overshadowed by her pretty and accomplished sister, Rose (Fiona Glascott), and bullied by her vicious, hypocritical employer, Miss Kelly (Brid Brennan), so she decides to go to America. Helped by her church, she gets a room in a Brooklyn boarding house and a job in a department store, gradually loses her shyness and reserve, and falls in love with a sweet-natured young Italian American, Tony Fiorello (Emory Cohen). But when Rose dies suddenly, Eilis returns to Enniscorthy to see her mother and stays long enough to be courted by a young man, Jim Farrell (Domhnall Gleeson), and to begin to see the town in a very different light. The time approaches when she is scheduled to return to America, and she finds herself torn between not just Tony and Jim, but also the small but familiar comforts of the town and a promising but uncertain future in America. She also has a secret that she hasn't shared with anyone, but which the vicious Miss Kelly learns through the Irish-American grapevine. That this dilemma should play itself out with such freshness is a tribute to John Crowley's direction and Nick Hornby's adaptation of Colm Tóibín's novel, but also in very large part to a brilliant performance by Ronan. It's the kind of understated acting that sometimes gets overlooked among performances that chew the scenery with more fervor, but it earned Ronan a well-deserved Oscar nomination. It has to be said that she is supported by splendid performances by Cohen and Gleeson, with Ronan demonstrating a different kind of rapport with each actor. A quiet triumph, but a triumph nevertheless.

Monday, October 10, 2016

Anna Karenina (Joe Wright, 2012)

|

| Jude Law and Keira Knightley in Anna Karenina |

Alexei Karenin: Jude Law

Count Vronsky: Aaron Taylor-Johnson

Stiva Oblonsky: Matthew Macfadyen

Dolly Oblonskaya: Kelly MacDonald

Kitty Scherbatsakaya: Alicia Vikander

Konstantin Levin: Domhnall Gleeson

Countess Vronskaya: Olivia Williams

Princess Betsy: Ruth Wilson

Director: Joe Wright

Screenplay: Tom Stoppard

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: Seamus McGarvey

Production design: Sarah Greenwood

Costume design: Jacqueline Durran

Anyone who wants to shake up an established film genre gets my support, even when what they do doesn't quite work. So I'm okay with what Joe Wright tries to do to the historical costume drama and the adaptation of a famous novel in his version of Anna Karenina. Which isn't to say that I think it works. What does work is the attempt by Wright and his screenwriter, Tom Stoppard, to redress the imbalance I've noted in my entries on two previous film adaptations of Tolstoy's novel, the ones directed by Clarence Brown in 1935 and Julien Duvivier in 1948: the neglect of the half of the novel that deals with Konstantin Levin. Domhnall Gleeson, the Levin of Wright's film, is hardly the Levin Tolstoy describes as "strongly built, broad-shouldered," but Gleeson seems to know what the character is about. And he's beautifully matched with Alicia Vikander, who gives another knockout performance as Kitty. Wright and Stoppard use their story as an effective foil for the obsessive, careless love of Anna and Vronsky. That it's only part of Levin's function in Tolstoy's novel, which gives us a view of Russian reform politics and social structure through Levin's eyes, just goes to show that you can't have everything when you're trying to adapt literature to a medium it isn't quite suited for. Wright has also cast brilliantly. As Karenin, Jude Law elicits sympathy for a character that can easily be reduced to a stock villain, as when Basil Rathbone played him in 1935. I also liked Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky, Anna's womanizing brother, and it's fun to see Macfadyen and Knightley together in completely different roles from Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, whom they played in Wright's 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. As Anna, Knightley sometimes looks a bit too much like a gaunt fashion model in the Oscar-winning costumes by Jacqueline Durran, and Taylor-Johnson lays on the preening a bit too much in his bedroom-eyed Vronsky, but they have real chemistry together. Seamus McGarvey's Oscar-nominated cinematography makes the most of Sarah Greenwood's production design. But the decision to film the story partly as as if it were being staged in some impossible, dreamlike theater, but also partly realistically, goes astray. It begins as if it were a comedy, with the philandering Oblonsky sneaking around from his wife both onstage and backstage. And throughout the film, reversions from realistic settings to the theater keep jarring the overall tone. There are occasionally some spectacular uses of the set, as when the horses in Vronsky's race run across a proscenium stage, and in his accident, horse and rider plunge off the stage. Here and elsewhere, Greenwood's design is extraordinarily ingenious. But the theater trope -- all the world's a stage? -- never resolves itself into anything thematically satisfying.

Sunday, October 9, 2016

Anna Karenina (Julien Duvivier, 1948)

|

| Vivien Leigh and Ralph Richardson in Anna Karenina |

Karenin: Ralph Richardson

Vronsky: Kieron Moore

Kitty: Sally Ann Howes

Levin: Niall MacGinnis

Princess Betsy: Martita Hunt

Countess Vronsky: Helen Haye

Sergei: Patrick Skipwith

Director: Julien Duvivier

Screenplay: Jean Anouilh, Guy Morgan, Julien Duvivier

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: Henri Alekan

Costume design: Cecil Beaton

If Greta Garbo is the best reason for seeing Clarence Brown's 1935 version of Anna Karenina, then Ralph Richardson is the best argument for watching this one. As Karenin, Richardson demonstrates an understanding of the character that Basil Rathbone failed to display in the earlier version. In a performance barely distinguished from his usual haughty villain roles, Rathbone played Karenin as a cuckold with a cold heart. Richardson wants us to see what Tolstoy found in Karenin: the wounded pride, the inability to stoop to tenderness that has been bred in him by long contact with Russian society and political status-seeking. Unfortunately, Richardson's role exists in a rather dull adaptation of the novel, directed by Julien Duvivier from a screenplay he wrote with Jean Anouilh and Guy Morgan. Although Vivien Leigh was certainly a tantalizing choice for the title role, she makes a fragile Anna -- no surprise, as she was recovering from tuberculosis, a miscarriage, and a bout with depression that seems to have begun her descent into bipolar disorder. At times, especially in the 19th-century gowns designed by Cecil Beaton, she evokes a little of the wit and backbone of Scarlett O'Hara, but she has no chemistry with her Vronsky, the otherwise unremembered Irish actor Kieron Moore. It's not surprising that producer Alexander Korda gave Moore third billing, promoting Richardson above him. The production, too, is rather drab, especially when compared to the opulence that MGM could provide in its 1935 heyday. There's a toy train early in the film that the special effects people try to pass off as full-size by hiding it behind an obviously artificial snowstorm. As usual, this Anna Karenina is all about building up to Anna's famous demise, this time by taking us into her foreboding nightmare about a railroad worker she saw at the beginning of her affair with Vronsky. And also as usual, the half of the novel dealing with Levin, Tolstoy's stand-in character, is scuttled. In this version, Levin is a balding middle-aged man whose only function is to be rejected by Kitty, who is then thrown over for Anna by Vronsky. There's a perfunctory scene that gives a happy ending to the Levin-Kitty story, but it adds nothing but length to the film. Some of the scenes featuring the supporting cast, especially those with Martita Hunt as Princess Betsy, bring the film to flickering life, but there aren't enough of them to overcome the general dullness.

Saturday, October 8, 2016

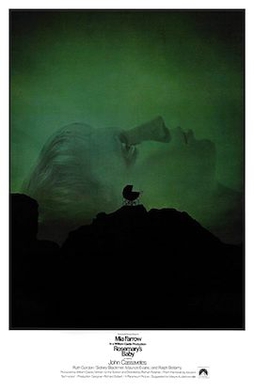

Rosemary's Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968)

I'm not boasting when I say that horror movies don't scare me. Sometimes I wish they did -- I'm missing out on the fun. It's just that since I learned to watch films analytically, studying performance and camerawork and storytelling, I usually see through the formulas of genre films. I know, for example, how to anticipate the surprises when you think that everything's okay and suddenly it isn't anymore -- e.g., the shocker moments in Wait Until Dark (Terence Young, 1967) or Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976). The best I can hope for from a scary movie is to feel unsettled, which is what Rosemary's Baby does to me. I've seen it often enough to know where it's going, but when it arrives -- especially in the conception scene and in the final reveal -- I invariably suspend my analysis long enough to be drawn in. As director and screenwriter, Roman Polanski is a master, providing lovely, creepy bits like the figures that tiptoe across the background in the scene in which Rosemary (Mia Farrow) thinks she's alone in the apartment. But to my mind the film succeeds mostly because of Farrow's performance: She brings just the right amount of vulnerability to the role -- she doesn't even need the makeup-induced pallor to convince us that she is prey to something terrible. It always strikes me as odd that she has never earned an Oscar nomination. But all the performances in Rosemary's Baby are top-notch, starting with the one that did win an Oscar, Ruth Gordon's deliciously vulgar Minnie Castevet, who pronounces "pregnant" as if it had three syllables. John Cassavetes succeeds in the difficult role of Guy, Rosemary's husband; he has to be plausible as the sympathetic, loving spouse at the start -- giving in to Rosemary's desire for the fatal apartment -- but just abrasive enough with his wisecracks to suggest the cynicism and careerism that leads him to sell his soul to the devil-worshipers. Ralph Bellamy also has to be plausibly caring as Dr. Sapirstein to convince Rosemary and the audience that he's on the right side, while also preparing us for later revelations. Bellamy had a long and interesting career, from the schnook who gets the girl taken away from him by Cary Grant in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937) and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1941), to the distinguished, gentlemanly, but sometimes sinister character in films like Trading Places (John Landis, 1983) and Pretty Woman (Garry Marshall, 1990). It's also good to see other veteran actors -- Sidney Blackmer, Elisha Cook Jr., and even that well-cured ham Maurice Evans -- doing fine ensemble work. Richard Sylbert's production design makes the most of the spooky gothic apartment house -- the exteriors are of the Dakota, but the interiors are sets. And Krzysztof Komeda, who had worked with Polanski in Poland, provides a score that's atmospheric without being overstated -- until it needs to be.

Friday, October 7, 2016

The Fallen Idol (Carol Reed, 1948)

The presidential campaign has put lying at the center of conversation this year, so The Fallen Idol fits right in: It's all about lying and its consequences. The film is usually categorized as a thriller, and it's undeniably suspenseful, but if you try to pigeonhole it as a thriller you have to deal with an ending that doesn't have the punch that we expect from the genre. I prefer to think of it as something less sexy, and probably much less enticing to those who haven't seen it: a moral fable. Revising his story "The Basement Room" into a screenplay, Graham Greene ensnares everyone in the film in their own lies, so that the audience, which knows the truth, is kept in suspense. Philippe (Bobby Henrey) is the young son of an ambassador, living in the embassy in London's Belgrave Square. His mother has been recuperating from a long illness in their home country, and when his father goes to see her, Philippe is left in the care of the butler, Baines (Ralph Richardson), and his wife, the housekeeper (Sonia Dresdel). Philippe idolizes Baines, who entertains him with made-up stories about his adventures in Africa -- in fact, he has never been out of England. Mrs. Baines, on the other hand, is strict and fussy, so he has learned to be sneaky about things like the pet snake he is hiding from her. When Mrs. Baines punishes him one day by sending him to his room, Philippe sneaks down the fire escape and follows Baines to a cafe, where Baines is meeting with Julie (Michèle Morgan), a woman who used to work at the embassy. Baines and Julie are in love, but she has found their relationship hopeless and has decided to break it off. When Philippe surprises them, Baines pretends that Julie is his niece; before the boy, they continue to talk about their relationship as if it were that of some other couple. After Julie leaves, Baines persuades Philippe not to talk about her around Mrs. Baines, telling him that she dislikes Julie. Back at the embassy, Baines tries to persuade his wife that their marriage is at an end, but she is having none of it. Learning that he's seeing another woman, she also lies, telling him that she's going away for a few days, then secretly stays behind to spy on him. All of this deception comes to a head with an accidental death that looks a lot like murder, with Philippe as a key witness. But Philippe has been so confused by the lies he's been told and the ones he's been asked to tell, that when the police question him he is in danger of leading them into a serious error of justice. Director Carol Reed brilliantly manages to hold most of the film to Philippe's point of view, giving the audience the double vision of what is actually happening and what Philippe thinks is happening. Nine-year-old Henrey, who had no significant film career afterward, is splendidly natural in the role, and Richardson brings a necessary ambiguity to the part of Baines. The film is also enlivened by Greene's secondary characters, including a chorus of housemaids who comment on the action, a clock-winder (Hay Petrie) who breaks the tension of an interrogation scene, and a scene at the police station where the cops and a prostitute (Dora Bryan) try to figure out what to do with Philippe, who has run away after the accident, barefoot and in pajamas, and refuses to tell them where he lives.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

Hôtel du Nord (Marcel Carné, 1938)

|

| Bernard Blier and Arletty in Hõtel du Nord |

Edmond: Louis Jouvet

Renée: Annabella

Pierre: Jean-Pierre Aumont

Louise Lecouvreur: Jane Marken

Emile Lecouvreur: André Brunot

Maltaverne: René Bergeron

Ginette: Paulette Dubost

Adrien: François Périer

Kenel: Andrex

Nazarède: Henri Bosc

The Surgeon: Marcel André

Prosper: Bernard Blier

Munar: Jacques Louvigny

The Commissioner: Armand Lurville

The Nurse: Génia Vaury

Director: Marcel Carné

Screenplay: Henri Jeanson, Jean Aurenche

Based on a novel by Eugène Dabit

Cinematography: Louis Née, Armand Thirard

Production design: Alexandre Trauner

Film editing: Marthe Gottié, René Le Hénaff

Music: Maurice Jaubert

I had seen Arletty in a movie only once before, as the fascinating, enigmatic Garance in Marcel Carné's great Children of Paradise (1945), so I was completely unprepared for her performance as the raucous streetwalker Raymonde in Hôtel du Nord. Raymonde shares a room in the hotel with Edmond, a photographer who is hiding out from his old cronies in the Parisian underworld. The film begins with a traveling shot along the canal that flanks the hotel, where we first see a young pair of lovers, Pierre and Renée, walking arm in arm. Inside the hotel, the residents are celebrating the first communion of the daughter of Maltaverne, a policeman who lives at the hotel. (It's a diverse household.) Pierre and Renée enter and request a room for the night, but instead of making love, they have decided on a suicide pact: He will shoot her, then kill himself. He holds up the first part of the bargain, but then chickens out. Edmond, who has been in his darkroom, hears the shot and breaks down the door, finding Renée apparently dead and Pierre cowering indecisively. Taking the gun from Pierre, Edmond urges him to flee. (The gun becomes a Chekhov's gun when Edmond first tosses it away and then recovers it and stashes it in a drawer.) Renée recovers from the gunshot, and Pierre, torn with guilt, turns himself into the police as an attempted murderer and is sent to prison. After she recuperates, Renée returns to the hotel to collect her things, and is offered a job there by Madame Lecouvreur, the wife of the proprietor. And so the story of the suicidal lovers begins to intertwine with that of Edmond and Raymonde. It's all neatly done, with a great deal of atmosphere (a word that Raymonde will give a particular spin to), much of it created by Alexandre Trauner's set, a re-creation in the studios at Billancourt of the actual hotel and the Canal St. Martin. The film's melodrama is alleviated by the ensemble work and the performances of Jouvet, who can switch from menacing to vulnerable in an instant, and Arletty, who makes the tough, worldly wise Raymonde often very funny. The film concludes with Carné's skillful staging of an elaborate Bastille Day sequence that anticipates the crowd scenes in Children of Paradise.

Wednesday, October 5, 2016

The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942)

So much has been written about the mishandling and mutilation of Orson Welles's second feature film that it's hard to see the Magnificent Ambersons that we have without pining for the one we lost. What we have is a fine family melodrama with a truncated and sentimental happy ending and an undeveloped and poorly integrated commentary on the effects of industrialization on turn-of-the-20th-century America. We also have some of the best examples of Welles's genius at integrating performances, production design, and cinematography -- all of which Welles supervised to the point of micromanagement. The interior of the Amberson mansion is one of the great sets in Hollywood film: It earned an Oscar nomination for Albert S. D'Agostino, A. Roland Fields, and Darrell Silvera, though the credited set designer, Mark-Lee Kirk, should have been included. Welles used the set as a grand stage, exploiting the three levels of the central staircase memorably with the help of Stanley Cortez's deep-focus camerawork. Welles later told Peter Bogdanovich that Frank Lloyd Wright, who was Anne Baxter's grandfather, visited the set and hated it: It was precisely the kind of domestic architecture that he had spent his career trying to eliminate, which, as Welles said, was "the whole point" of the design. As for the performances, Agnes Moorehead received a supporting actress nomination, the first of four in her career, for playing the spinster aunt, Fanny Minafer. She's superb, especially in the "kitchen scene," a single long take in which her nephew, George (Tim Holt), scarfs down strawberry shortcake as she worms out of him the information that Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten) has renewed his courting of George's widowed mother, Isabel (Dolores Costello), which is especially painful for Fanny, who had hopes of attracting Eugene herself. Holt, an underrated actor, holds his own here and elsewhere -- he is, after all, the central character, the spoiled child whose selfishness ruins the chances for happiness of so many of the film's characters. We can mourn the loss of Welles's cinematic flourishes that were apparently cut from the film, but to my mind the chief loss is the effective integration of the theme initiated when Eugene, who has made his fortune developing the automobile, admits that the industrial progress it represents "may be a step backward in civilization" and that automobiles are "going to alter war and they're going to alter peace." Welles was speaking from his own life, as Patrick McGilligan observes in his book Young Orson. Welles's father, Dick Welles, had been involved in developing automobile headlights -- the very thing in which Fanny invests and loses her inheritance -- and was the proud driver of the first automobile on the streets of Kenosha, Wisconsin, Welles's home town. The Magnificent Ambersons would have been much richer if Welles had been able to make the statement about the automobile that he later told Bogdanovich was central to his concept of the film.

Tuesday, October 4, 2016

Dazed and Confused (Richard Linklater, 1993)

|

| Rory Cochrane and Matthew McConaughey in Dazed and Confused |

Monday, October 3, 2016

Red Dust (Victor Fleming, 1932)

Victor Fleming is the credited director on two of the most beloved films in Hollywood history: Gone With the Wind (1939) and The Wizard of Oz (1939). I say "credited director" because it's widely known that many other directorial hands were involved in both movies. Fleming took over the former only after George Cukor had been fired from it (reportedly on the insistence of Clark Gable). Some of Cukor's scenes remain in the film, and others were reportedly directed by Sam Wood and King Vidor, but GWTW is mostly the product of its obsessive, micromanaging producer, David O. Selznick. The Wizard, too, was primarily the work of its producers, Mervyn LeRoy and Arthur Freed; once again a director, Richard Thorpe, was fired from the film before Fleming was brought on, LeRoy directed some of the scenes, as did Cukor and Norman Taurog, and the Kansas scenes are well-known as having been directed by Vidor after Fleming went to work on GWTW. So was Fleming more than just a replacement director or a fixer of movies gone astray? The best evidence that Fleming was a pretty good director on his own is Red Dust, a funny, sexy adventure romance that established Gable, especially when he was teamed with Jean Harlow, as a top box-office draw. Fleming demonstrates a sure hand with the material, keeping it from bogging down in melodramatic mush in the scenes between Gable and Mary Astor. The action is set in Hollywood's idea of a rubber plantation in French Indochina -- what Vietnam was called back when Americans were pronouncing Saigon as "SAY-gone," if the movie is to be trusted. Dennis Carson (Gable) manages the plantation when he is not being distracted by the arrival first of Vantine (Harlow), a shady lady, and then of Barbara Willis (Astor) and her husband, Gary (Gene Raymond), an engineer who has been sent to survey an expansion of the plantation. Carson and Vantine have been spending several weeks of unwedded bliss before the Willises arrive, but pretty soon he is making a play for Mrs. Willis, using the old trick of sending the husband off to survey the swamps while she remains behind. All of this is handled with delicious innuendo, possible only because the Production Code had not yet gone into effect: for example, the scene in which Vantine rinses off in a rain barrel while Carson looks on (and in), or the fact that Carson and Mrs. Willis's adultery goes unpunished except for a flesh wound. Both Harlow and Astor sashay around in improbable barely-there finery by Adrian. Fleming went on to make another pre-Code delight with Harlow, the screwball comedy Bombshell (1933), which alludes to the Hays Office's concerns about Red Dust. John Lee Mahin was screenwriter on both films, though some of the better lines in Red Dust were contributed by the uncredited Donald Ogden Stewart. The movie is marred only for today's viewers by some period racism: the colonialist attitude toward the native laborers as "lazy" and the giggling Chinese houseboy played by Willie Fung.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)