A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, June 30, 2016

The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940)

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (John Huston, 1948)

I love Turner Classic Movies -- obviously, because it's where I see so many of the films I comment on here. But I don't always love the introductory segments they do for some of their films. It can be a real irritant when they bring on a celebrity as a "guest programmer." Some of them are excellent: Sally Field displays real knowledge and insight about the films she introduces. But The Treasure of the Sierra Madre was introduced by Candice Bergen, who is normally a witty and charming person, but seemed to have no idea about the movie she was showcasing. She admitted to interviewer Robert Osborne that she hadn't seen it for 35 years, and that she recalled it as this "little" movie that she surmised had been filmed on a small budget in locations maybe 20 minutes from the studio. To Osborne's discredit, he made no attempt to correct her: Warner Bros. gave it what was a generous budget for the time of $3 million, and it was mostly filmed on location -- a rarity for the time -- in the state of Durango and the town of Tampico, Mexico. (Some scenes had to be shot in the studio, of course, and it's easy to spot the artificial lighting and hear the sound stage echoes in these, which don't match up to the ones Ted McCord filmed on location.) It's hardly a "little" movie, either: It has a generosity of characterization in both the screenplay by Huston from B. Traven's novel and in the performances of Humphrey Bogart, Walter Huston, and Tim Holt. It's always shocking to realize that Bogart failed to be nominated for an Oscar for his performance as the bitter, paranoid Fred C. Dobbs. I mean, who today remembers some of the performances that were nominated instead: Lew Ayres in Johnny Belinda (Jean Negulesco)? Dan Dailey in When My Baby Smiles at Me (Walter Lang)? Clifton Webb in Sitting Pretty (Lang)? To the Academy's credit, Huston won as both director and screenwriter, and his father, Walter, won the supporting actor Oscar -- the first instance of someone directing his own father to an Academy Award for acting, which Walter Huston's smartly delineated old coot certainly deserved. But let's also put in a word for Tim Holt, who had one of the odder careers of a potential Hollywood star: He gave good performances in some of the best movies to come out of the studios in the 1940s, including The Magnificent Ambersons (Orson Welles, 1942) and My Darling Clementine (John Ford, 1946), and was a handsome and capable presence in them. But even after working for Welles, Ford, and Huston, after The Treasure of the Sierra Madre he went back to performing in B-movie Westerns, which had been the stock in trade of his father, Jack Holt (who has a small part as a flophouse bum in this film). His heart seemed not to be in the movie business, and he retired to his ranch, making only a few appearances after 1952.

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Daisy Kenyon (Otto Preminger, 1947)

|

| Joan Crawford, Dana Andrews, and Henry Fonda in Daisy Kenyon |

Dan O'Mara: Dana Andrews

Peter Lapham: Henry Fonda

Lucille O'Mara: Ruth Warrick

Mary Angelus: Martha Stewart

Rosamund O'Mara: Peggy Ann Garner

Marie O'Mara: Connie Marshall

Coverly: Nicholas Joy

Lucille's Attorney: Art Baker

Director: Otto Preminger

Screenplay: David Hertz

Based on a novel by Elizabeth Janeway

Cinematography: Leon Shamroy

Art direction: George W. Davis, Lyle R. Wheeler

Film editing: Louis R. Loeffler

Music: David Raksin

Daisy Kenyon is an underrated romantic drama from an often underrated director. Otto Preminger gives us an unexpectedly sophisticated look -- given the Production Code's strictures about adultery -- at the relationship of an unmarried woman, Daisy, to two men, one of whom, Dan O'Mara, is married, the other a widowed veteran, Peter Lapham, who is suffering from PTSD -- not only from his wartime experience but also from the death of his wife. It's a "woman's picture" par excellence, but without the melodrama and directorial condescension that the label suggests: Each of the three principals is made into a credible, complex character, not only by the script and director but also by the performances of the stars. Crawford is on the cusp of her transformation into the hard-faced harridan of her later career: She had just won her Oscar for Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), and was beginning to show her age, which was 42, a time when Hollywood glamour becomes hard to maintain. But her Daisy Kenyon has moments of softness and humor that restore some of the glamour even when the edges start to show. Andrews, never a star of the magnitude of either Crawford or Fonda, skillfully plays the charming lawyer O'Mara, trapped into a marriage to a woman who takes her marital frustrations out on their two daughters. Although he is something of a soulless egoist, he finds a conscience when he takes on an unpopular civil rights case involving a Japanese-American -- and loses. Set beside his two best-known performances, in Preminger's Laura (1944) and in William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), his work here demonstrates that he was an actor of considerable range and charisma. Fonda is today probably the most admired of the three stars, but he had always had a distant relationship with Hollywood: He suspended his career for three years to enlist in the Navy during World War II, and after making Daisy Kenyon to work out the remainder of his contract with 20th Century-Fox he made a handful of films before turning his attention to Broadway, where he stayed for eight years, until he was called on to re-create the title role in the film version of Mister Roberts (John Ford and Mervyn LeRoy, 1955). Of the three performances in Daisy Kenyon, Fonda's seems the least committed, but his instincts as an actor kept him on track.

Monday, June 27, 2016

Anna Karenina (Clarence Brown, 1935)

|

| Basil Rathbone and Greta Garbo in Anna Karenina |

Count Vronsky: Fredric March

Sergei: Freddie Bartholomew

Kitty: Maureen O'Sullivan

Countess Vronsky: May Robson

Alexei Karenin: Basil Rathbone

Stiva: Reginald Owen

Konstantin Levin: Gyles Isham

Director: Clarence Brown

Screenplay: Clemence Dane, Salka Viertel, S.N. Behrman

Based on a novel by Leo Tolstoy

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Costume design: Adrian

One of the problems with adapting Tolstoy's novel to another medium is that while everyone knows the story of the title character, who throws herself under a train at the end, at least half of the book is not about her. It's about Konstantin Dmitrievich Levin, the burly intellectual who is preoccupied with the problems of a changing Russia. Though Levin's is also a love story -- he falls for Anna's sister-in-law, Kitty, who initially spurns him because she's in love with Count Vronsky, the man for whom Anna leaves her husband -- he's Tolstoy's surrogate in the novel, just as Pierre Bezukhov is in War and Peace. Downplaying Levin's role in any adaptation of Anna Karenina is as gross a distortion of the novel as omitting Pierre from an adaptation of War and Peace. But it has been done, and often, given that the melodrama of a doomed love is far easier to sell to an audience than the problems of a reformist landowner. In this MGM version of Anna Karenina, Levin virtually disappears: He's played by a tall, bland English actor named Gyles Isham, whose film career was brief and undistinguished. Kitty is at least played by a star, Maureen O'Sullivan, although her presence in the film is largely designed to introduce the character of Vronsky and to suffer disappointment when he throws her over for Anna. This was Greta Garbo's second turn at playing Anna: She had filmed a silent version, titled Love (Edmund Goulding, 1927), with John Gilbert as Vronsky. (The earlier version omitted not only Levin but also Kitty, and was filmed with two endings: In the one aimed at the American market, Anna doesn't commit suicide but is reunited with Vronsky after Karenin's death.) Garbo is the best reason for seeing the 1935 version, although MGM, with David O. Selznick producing, gave it a lavish setting, with cinematography by Garbo's favorite photographer, William H. Daniels. It opens with a spectacularly filmed sequence in which Vronsky and his fellow officers attend a banquet, with the camera performing a long tracking shot down a seemingly endless table laden with food. Unfortunately, Fredric March is miscast as Vronsky, turning the dashing young officer into a rather somber middle-aged man; he and Garbo are sorely lacking in chemistry together. The screenplay by Clemence Dane, Salka Viertel, and S.N. Behrman does what it can to pull together the pieces carved out of Tolstoy, but the ending, even Anna's suicide, feels flat and perfunctory. In the novel, Anna's disintegration, aided by isolation from society, by illnesses both mental and physical, and by her addiction to opiates, is dealt with at some harrowing length, but trimming much of that background means that she appears to be driven to her ghastly end solely by losing her young son, Sergei, and by the cruelty of Karenin. Tolstoy, of course, gives us deep background on Karenin that, while it doesn't absolve him completely makes him far more credible than a mere Rathbone villain.

Sunday, June 26, 2016

Two by Jacques Feyder

|

| Jacques Feyder |

Gribiche (Jacques Feyder, 1926)

The young actor Jean Forest had been discovered by Feyder and his wife, Françoise Rosay, and he starred in three films for the director, of which this was the last. It's a peculiar fable about charity. Forest plays Antoine Belot, nicknamed "Gribiche," who sees a rich woman, Edith Maranet (Rosay), drop her purse in a department store and returns it to her, spurning a reward. Edith is a do-gooder full of theories about "social hygiene." Impressed by the boy's honesty, Edith goes to his home, a small flat above some shops, where he lives with his widowed mother, Anna (Cécile Guyon), and proposes that she adopt Gribiche and educate him. Anna is reluctant to give up the boy, but Gribiche, knowing that Anna is being courted by Phillippe Gavary (Rolla Norman), and believing that he stands in the way of their marriage, agrees to the deal. When her rich friends ask about how she found Gribiche, Edith tells increasingly sentimental and self-serving stories -- dramatized by Feyder -- about the poverty in which she found him and his mother. But the boy is unhappy with the cold, sterile environment of Edith's mansion and the regimented approach to his education, and on Bastille Day, when the common folk of Paris are celebrating in what Edith regards as "unhygienic" ways, he finds his way back to his mother's home. Edith is furious, but eventually is persuaded to see reality and agrees to let him live with Anna and Phillippe, who have married, while she pays for his education. The whole thing is implausible, but the performances of Forest and Rosay, and especially the production design by Lazare Meerson, make it watchable and occasionally quite charming.

Carnival in Flanders (Jacques Feyder, 1935)

Feyder's best-known film is something of a feminist fable, a kind of inversion of Lysistrata, in which the women of Boom, a village in 17th century Flanders that is occupied by the Spanish save the town from the pillage and plunder that the men of the village expect. Françoise Rosay plays the wife of the burgomaster (André Alerme), who holes up in his house, pretending to have died. The other officials of the town likewise sequester themselves. But the merry wives of Boom decide to wine, dine, and otherwise entertain the occupying Spaniards. It's all quite saucily entertaining, though undercut by a tiresome subplot (suspiciously reminiscent of that in Shakespeare's own play about merry wives) involving the burgomaster's daughter (Micheline Chierel) and her love for the young painter Julien Brueghel (Bernard Lancret), of whom the burgomaster disapproves. Again, Rosay's performance is a standout, as is Lazare Meerson's design: The village, with its evocation of the paintings of the Flemish masters, was created in a Paris suburb, with meticulous attention to detail, including the men's unflattering period costumes, designed by Georges K. Benda. The cinematography is by the American Harry Stradling Sr., who built his reputation in Europe before returning to Hollywood.

Saturday, June 25, 2016

Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

Friday, June 24, 2016

Rio Bravo (Howard Hawks, 1959)

I could never countenance plagiarism, but as they say, if you're going to steal, steal from the best. Even if you're Howard Hawks stealing from Howard Hawks, which happens almost shamelessly in Rio Bravo. No one who loves Hawks's Red River (1948) as much as I do could fail to miss how much of Rio Bravo is, let us say, borrowed from that film. There's the byplay between Sheriff John T. Chance (John Wayne) and Stumpy (Walter Brennan), which echoes that of Dunson (Wayne) and Groot (Brennan) in Red River. Ricky Nelson's young gun Colorado Ryan is a reworking of Montgomery Clift's Matthew Garth. And Angie Dickinson's Feathers could almost be a parody of Joanne Dru's motormouth Tess Millay. But the Hawksian borrowings don't stop with Red River. When Feathers kisses Chance for the first time and then goes in for a second kiss in which he participates more enthusiastically, she comments, "It's better when two people do it," which is a direct steal from a similar scene in To Have and Have Not (Hawks, 1944) when "Slim" (Lauren Bacall) tells "Steve" (Humphrey Bogart), "It's even better when you help." The two movies share not only a director but also a screenwriter, Jules Furthman, who is joined in Rio Bravo by Leigh Brackett, who earlier worked together on another Bogart-Bacall-Hawks movie, The Big Sleep (1946). Even the composer of the score for Rio Bravo, Dimitri Tiomkin, gets into the borrowing game, taking a theme from his score for Red River and handing it over to lyricist Paul Francis Webster for the song, "My Rifle, My Pony, and Me," sung by Dean Martin's Dude and Nelson's Colorado. Rio Bravo isn't as great a movie as Red River by a long shot, and it probably signals some creative exhaustion on Hawks's part that he not only borrowed so heavily from his earlier work but also felt it necessary to remake Rio Bravo in two thinly disguised versions also starring Wayne, as El Dorado (1966) and Rio Lobo (1970). But is there a more entertaining self-plagiarism, and a surer demonstration of what made Hawks one of the great filmmakers?

Thursday, June 23, 2016

The Walk (Robert Zemeckis, 2015)

Many years ago in Rome I went with a group of other tourists to the top of the dome of St. Peter's where, stepping out onto the narrow observation platform, I experienced a moment of real terror. Stretching out below me, beyond a barrier that seemed to be only knee-high but was probably at least waist-high, were the ridges of the dome, extending downward like railway tracks into the abyss. They were dotted with metal disks that, the guide told us, mountaineers would place candles on to illuminate the dome at Christmastime. As I shrunk back as far from the guard rail as possible, I realized something about my fear of heights: I'm not afraid of falling so much as jumping. I realized that a momentary psychotic break could easily cause me to hurdle the barrier and plunge to my death. Maybe it was the perspective of the receding ridges that awoke this in me, but I had never experienced anything like it before, and even at the rim of the Grand Canyon I have never experienced it quite the same again. I have it under control. But I'm glad I didn't see The Walk in 3D in theaters, where I've heard that audience members fainted or fled as Philippe Petit (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) took his walk between the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Even watching it in 2D on a TV screen brought back that experience on the dome. And not so much during the walk on the wire as during the preparations, when Petit clambers around on the verge of the building to set up his equipment: There's something about being in the proximity of the crisis moment that knots me up. During the walk itself, the self-possession of Gordon-Levitt's Petit is somehow oddly calming. All of this is to say that The Walk is an oddly unique film in its success at portraying the narrowness of the line between heroism and foolishness. For Petít's walk was singularly foolish, and Gordon-Levitt does a wonderful job of presenting him as an engaging personality with an eccentric obsession that most of us can only marvel at and reluctantly admire. Zemeckis, who wrote the screenplay with Christopher Browne, deserves credit for blending characterization with state-of-the-art film technology that for once isn't used to fling things at the audience but to draw them into a precarious state. It felt like a return to the engaging Zemeckis of the Back to the Future films (1985, 1989, 1990) after the overblown Forrest Gump (1994), Contact (1997), and Cast Away (2000). Remarkably, the film gets away without sentimentalizing the calamitous fate of the twin towers and their inhabitants, although seeing them re-created with cinematic technology does create a subtext for Petit's performance. Only at the very end, when the image of the towers fades into a sunlit "11," do we get a subtle evocation of that date in September 2001.

Wednesday, June 22, 2016

Stalag 17 (Billy Wilder, 1953)

After their success with Sunset Blvd. (1950), Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett went their separate ways. They had been one of the most successful teams in Hollywood history since 1938, when they began collaborating as screenwriters, and then as a producer (Brackett), director (Wilder), and co-writer team starting with Five Graves to Cairo in 1943. But Wilder decided that he wanted to be a triple-threat: producer, director, and writer. His first effort in this line, Ace in the Hole (1951), was, however, a commercial flop. so he seems to have decided to go for the sure thing: film versions of plays that had been Broadway hits and therefore had a built-in attraction to audiences. His next three movies, Stalag 17, Sabrina (1954), and The Seven Year Itch (1955), all fell into this category. But what Wilder really needed was a steady writing collaborator, which he didn't find until 1957, when he teamed up with I.A.L. Diamond for the first time on Love in the Afternoon. The collaboration hit pay dirt in 1959 with Some Like It Hot, and won Wilder his triple-threat Oscar with The Apartment (1960). Which is all to suggest that Stalag 17 appeared while Wilder was in a kind of holding pattern in his career. It's not a particularly representative work, given its origins on stage which bring certain expectations from those who saw it there and also from those who want to see a reasonable facsimile of the stage version. The play, set in a German P.O.W. camp in 1944, was written by two former inmates of the titular prison camp, Donald Bevan and Edmund Trczinski. In revising it, Wilder built up the character of the cynical Sgt. Sefton (William Holden), partly to satisfy Holden, who had walked out of the first act of the play on Broadway. Sefton is in many ways a redraft of Holden's Joe Gillis in Sunset Blvd., worldly wise and completely lacking in sentimentality, a character type that Holden would be plugged into for the rest of his career, and it won him the Oscar that he probably should have won for that film. But it's easy to see why Holden wanted the role beefed up, because Stalag 17 is the kind of play and movie that it's easy to get lost in: an ensemble with a large all-male cast, each one eager to make his mark. Harvey Lembeck and Robert Strauss, as the broad comedy Shapiro and "Animal," steal most of the scenes -- Strauss got a supporting actor nomination for the film -- and Otto Preminger as the camp commandant and Sig Ruman as the German Sgt. Schulz carry off many of the rest. The cast even includes one of the playwrights, Edmund Trczinski, as "Triz," the prisoner who gets a letter from his wife, who claims that he "won't believe it," but an infant was left on her doorstep and it looks just like her. Triz's "I believe it," which he obviously doesn't, becomes a motif through the film. Bowdlerized by the Production Code, Stalag 17 hasn't worn well, despite Holden's fine performance, and it's easy to blame it for creating the prison-camp service comedy genre, which reached its nadir in the obvious rip-off Hogan's Heroes, which ran on TV for six seasons, from 1965 to 1971.

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951)

|

| Jan Sterling and Kirk Douglas in Ace in the Hole |

Lorraine Minosa: Jan Sterling

Herbie Cook: Robert Arthur

Jacob Q. Boot: Porter Hall

Al Federber: Frank Cady

Leo Minosa: Richard Benedict

Sheriff Gus Kretzer: Ray Teal

Director: Billy Wilder

Screenplay: Billy Wilder, Lesser Samuels, Walter Newman

Cinematography: Charles Lang

Music: Hugo Friedhofer

Ace in the Hole has a reputation as one of Billy Wilder's most bitter and cynical films. But today, when media manipulation is such a commonplace topic of discourse, it seems a little shy of the mark: After all, the manipulation in the movie seems to be the work of one man, Chuck Tatum, who milks the story of a man trapped in a cave-in to rehabilitate his own career. Other media types, including the editor and publisher of the small Albuquerque paper Tatum uses to springboard back into the big time, seem more conscientious about telling the truth. As we've seen time and again, it's the audience (the ratings, the ad dollars) that drives the news, with the journalists often reluctantly following. Wilder's screenplay, written with Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman, certainly blames them (or us) for the magnitude of Tatum's manipulation, but the focus on one unscrupulous reporter makes the media the primary evil. Maybe it's just because I've been following the Trump campaign this summer, and just watched the stunning eight-hour documentary about O.J. Simpson on ESPN, O.J.: Made in America, that I'm inclined to blame the great imbalance in what gets covered as news on the audience at least as much as on the reporters and editors who cater to their tastes. That said, Ace in the Hole is pretty effective movie-making -- so much so that it's surprising to learn that it was one of Wilder's biggest flops. It has some terrific lines, like the one from Lorraine, the trampy wife of the cave-in victim: When told by Tatum that she should go to church to keep up the appearance that she's still in love with her husband, she retorts, "I don't go to church. Kneeling bags my nylons." Porter Hall, one of Hollywood's great character actors, is wonderfully wry as the editor forced by Tatum into hiring him, and Robert Arthur, one of Hollywood's perennial juveniles, does good work as Herbie, the young reporter corrupted by Tatum's ambition. Sterling spent her long career typecast as a floozy, but that's probably because she did such a good job of it. Douglas is, as usual, intense, which has always made me feel a little ambivalent about him as an actor; I wish he would unclench occasionally, but I admire his willingness to take on such an unlikable role and make the character ... well, unlikable. He's the right actor for Wilder, who seems to be on the verge of trying to give Tatum a measure of redemption, but can't quite let himself do it.

Monday, June 20, 2016

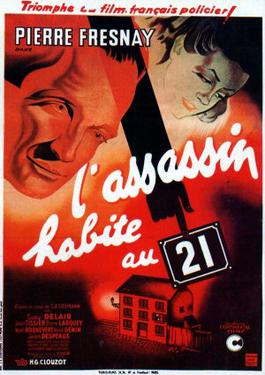

The Murderer Lives at Number 21 (Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1942)

Henri-Georges Clouzot is best-known today for the chilling Diabolique (1955) and the nail-biter The Wages of Fear (1953), but his first feature was a comedy-mystery somewhat in the manner of The Thin Man (W.S. Van Dyke, 1934). In The Murderer Lives at Number 21, police inspector Wenceslas Vorobechik (Pierre Fresnay), known as Wens, sets out to solve a series of murders in which the killer leaves a calling card: Monsieur Durand. Eventually, he is aided (and occasionally stymied) by his mistress, Mila Milou (Suzy Delair), who gets involved in the case because she thinks the celebrity of bringing the killer to justice would help her nascent career as a singer and actress. Clouzot made the film for a company backed by the occupying German forces, who wanted films to replace American imports. The movie shows no sign of Nazi propaganda, and there are those who claim that Clouzot inserted subtle anti-German jokes into the film. It was based on a novel by Stanislas-André Steenman, who worked on the screenplay with Clouzot, who brought the characters of Wens and Mila over from an earlier short film. Wens and Mila have a relationship somewhat reminiscent of Nick and Nora Charles, although no Thin Man film ever contained a scene like the one in which Mila squeezes out the blackheads on Wens's face -- a gratuitous bit that is presumably designed to show the intimacy of their relationship. Compared to Clouzot's later work, it's a slight but amusing movie, enlivened by the oddball inhabitants of the boarding house at No. 21 Avenue Junot that Wens moves into, disguising himself as a clergyman, after he receives a tip that the murderer lives there.

Sunday, June 19, 2016

The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (Charles Reisner, 1929)

Designed to show off the novelty of sound -- and, in two sequences, the coming novelty of Technicolor -- The Hollywood Revue of 1929 was enthusiastically received by critics and audiences, though it lost the best picture Oscar to The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929). Today, both movies are creaky antiques, despite the effort that MGM put into producing them. In fact, The Hollywood Revue often seems like an attempt to promote The Broadway Melody, which had opened three and a half months earlier, since it gives prominent spots to that film's stars, Charles King, Bessie Love, and Anita Page. The rest of it feels a lot like amateur night at MGM, as the studio's stars are trotted out for songs and skits that often feel tired and incoherent. In a few years, MGM would be boasting that it had more stars than there are in heaven, but many of the stars showcased in the Revue are forgotten today -- like King, Love, and Page -- or were on the wane -- like John Gilbert, Marion Davies, and Buster Keaton. The ones that remained stars, like Jack Benny and Joan Crawford, did so by reinventing themselves. The Revue, which modeled itself on theatrical conventions like the minstrel show and vaudeville, both of which were on the outs, failed to break ground for the Hollywood musical: It would take a few years for Warner Bros. to do that, with 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933) and the unfettered imagination of Busby Berkeley taking the backstage musical formula of The Broadway Melody and some of Sammy Lee's choreographic tricks from the Revue -- including overhead kaleidoscope shots -- and improving on them. The Revue has a few highlights even today: Joan Crawford trying a little too hard to sparkle as she sings (passably) and dances (clunkily); Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy in their first sound film, doing a magic act with Jack Benny's intervention; Cliff Edwards and the Brox Sisters doing "Singin' in the Rain," which gets a Technicolor reprise with most of the company at the film's end; Keaton acrobatically clowning his way (silently) through an "underwater" drag routine; and Norma Shearer and John Gilbert in Technicolor performing a bit of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, first as Shakespeare wrote it and then in 1929's slang. To get to them, however, you have to sit through a lot of dud routines and dated songs like Charles King's paean to maternity, "Your Mother and Mine," which must have been aimed right at the mushy heart of Louis B. Mayer.

Saturday, June 18, 2016

Tillie's Punctured Romance (Mack Sennett, 1914)

Tillie's Punctured Romance was Mack Sennett's first venture into feature-length production, and perhaps the first feature-length comedy ever made. Despite the later reputation of Charles Chaplin, it was designed as a starring vehicle and film debut for Marie Dressler, then the much bigger star. It was adapted from her Broadway hit, Tillie's Nightmare, and Dressler claimed that it was she who persuaded Sennett to cast Chaplin as her leading man. Adding Sennett's then-lover Mabel Normand, who also had a hand in developing Chaplin's early career, created a wonderful dynamic, but the teaming was never repeated: Chaplin's ambitions led him into writing and directing his own films; Normand and Sennett split in 1918, and her career suffered from her drug addiction and association with director William Desmond Taylor, whose murder in 1922 caused a scandal; Dressler was unable to establish a film career after the failure of two short films in which she also played Tillie, though she returned to the screen in 1927 after a nine-year absence. It's a shame, because Dressler was one of the few comic actresses capable of upstaging Chaplin, as their scenes together demonstrate. She had a rare gift for over-the-top physical comedy, which was Sennett's forte. For this anarchic comery, he marshaled all of his regular company, including Mack Swain and Chester Conklin, as well as the Keystone Kops, without ever eclipsing Dressler. Later in her career, Dressler would evoke pathos as well as laughs, but Sennett never lets Tillie be anything but a clown, except at the very ending, when she and Mabel share in their triumph over Chaplin's con man.

Friday, June 17, 2016

The Patsy (King Vidor, 1928)

King Vidor is not generally known as a comedy director, and The Patsy shows why: Vidor seems to have no sense of how to set up a gag, merely letting the skilled comic acting of Marion Davies as the put-upon younger sister, Pat Hamilton, and Marie Dressler and Dell Henderson as her parents, do the work. The result is a giddy, silly movie with a good many laughs, but not much coherence. Pat is smitten with Tony Anderson (Orville Caldwell), but her sister, Grace (Jane Winton) has her hooks in him -- until, that is, she starts running around with playboy Billy Caldwell (Lawrence Gray). Pat tries to win Tony by memorizing joke books -- for a silent film The Patsy is unusually heavy on gags in the intertitles -- but this only makes her parents, especially her domineering mother, think she's gone mad. Then she tries to make Tony jealous by pretending that she's in love with Billy, arriving at his house when he's drunk and trying to woo him by imitating movie stars like Mae Murray, Lillian Gish, and Gloria Swanson. Davies's skill and charm makes all of this palatable if not plausible, but almost every scene is stolen by Dressler, who uses face and body to upstage everyone. Vidor and Davies teamed again the same year for Show People, another comedy.

Thursday, June 16, 2016

The Divine Lady (Frank Lloyd, 1929)

Frank Lloyd is a director nobody remembers today except for the fact that he won two best director Oscars. Unfortunately, they were for movies that almost no one except film scholars and Oscar completists watch today: this one and Cavalcade (1933). His other distinction is that his Oscar for The Divine Lady is the only one that has ever been awarded for a film that was not nominated for best picture.* (As if to make up for this anomaly, Mutiny on the Bounty, which Lloyd also directed, won the best picture Oscar for 1935, but he lost the directing Oscar to John Ford for The Informer.) It's a moderately entertaining film about the affair of Emma Hamilton (Corinne Griffith) and Lord Horatio Nelson (Victor Varconi) -- a story better told in That Hamilton Woman (Alexander Korda, 1941) with Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier as the lovers. Griffith is one of those silent stars whose career didn't make it into the sound era, reportedly because her voice was too nasal. She was, however, considered* for the best actress Oscar, which went to Mary Pickford for Coquette. She doesn't have to speak in The Divine Lady: Although it has a synchronized music track, including Griffith supposedly singing (but probably dubbed) "Loch Lomond", and sound effects, including cannon fire during Nelson's naval battles, there is no spoken dialogue. The only truly standout performance is a small one by Marie Dressler as Emma's mother: She has a funny slapstick bit at the beginning of the movie, but disappears from the movie far too soon. The cinematography by John F. Seitz (miscredited as "John B. Sietz" in the opening titles) was also considered* for an Oscar, but it went to Clyde De Vinna for White Shadows in the South Seas (W.S. Van Dyke and Robert J. Flaherty, 1928).

*If you want to get technical about it, there were no official nominations in any of the Oscar categories for the 1928-29 awards. What are usually regarded as nominees are the artists and films that Academy records show were under consideration for awards. In Lloyd's case, he was also under consideration for directing the films Drag and Weary River during the same time period, but when his win was announced, only The Divine Lady -- which was not considered for a best picture Oscar -- was specified.

*If you want to get technical about it, there were no official nominations in any of the Oscar categories for the 1928-29 awards. What are usually regarded as nominees are the artists and films that Academy records show were under consideration for awards. In Lloyd's case, he was also under consideration for directing the films Drag and Weary River during the same time period, but when his win was announced, only The Divine Lady -- which was not considered for a best picture Oscar -- was specified.

Wednesday, June 15, 2016

On the Waterfront (Elia Kazan, 1954)

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1964)

Imagine Gertrud as a Hollywood "women's picture" of the 1940s or '50s, with Olivia de Havilland, perhaps, as Gertrud, and Claude Rains as her husband, Montgomery Clift as her young lover, and Walter Pidgeon as the old flame who comes back into her life. It's not hard to do, given that the play by Hjalmar Söderberg on which Carl Theodor Dreyer based his film has all the elements of the genre: a woman trapped in a sterile marriage; an ardent young lover who appeals to the artist trapped in her; another man who represents the road not taken that might have led her to fulfillment if she hadn't discovered that he was more committed to his work than to her. And it ends the way the Hollywood film might have: After Gertrud has rejected those three lovers and gone off to Paris with yet another man -- George Brent, perhaps -- who seemed to give her the opportunity to find herself, we see them reunite 30 or 40 years later, when she has settled into a sadly contented solitary life. There would have been a Max Steiner or Alfred Newman score to draw tears at the crisis moments -- as when, for example, Gertrud discovers that her young lover has boasted of his affair with her at a party also attended by the old flame. But this is a "women's picture" of ideas, largely about the nature of love and the way we can be deceived in the pursuit of it. And there are no melodramatic moments, merely extended conversations in which the participants rarely, if ever, make eye contact. As Gertrud, Nina Pens Rode maintains a gaze into the middle distance, rarely even blinking, whether she's telling her husband (Bendt Rothe) that she's leaving him, declaring her love for the young musician (Baard Owe) who later boasts of his conquest, or reminiscing about their past together with her old flame (Ebbe Rode). But the faint flicker of thought and emotion always plays over her face, as Henning Bendtsen's camera gazes steadily at her. It is, for those raised on the Hollywood version, something of a trying and even boring film, but for those who understand what Dreyer is doing -- grabbing the viewer's eye and keeping it trained on the characters, through long, long takes and subtle camera moments -- it creates a psychological tension that is unnerving. Dreyer makes more conventional directors' work seem frantic and frivolous.

Monday, June 13, 2016

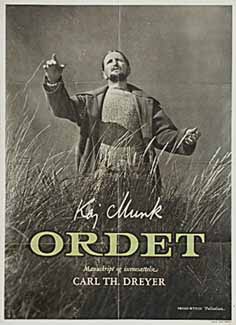

Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955)

As a non-believer, I find the story told by Ordet objectively preposterous, but it raises all the right questions about the nature of religious belief. Ordet, the kind of film you find yourself thinking about long after it's over, is about the varieties of religious faith, from the lack of it, embodied by Mikkel Borgen (Emil Hass Christensen), to the mad belief of Mikkel's brother Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye) that he is in fact Jesus Christ. Although Mikkel is a non-believer, his pregnant wife, Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), maintains a simple belief in the goodness of God and humankind. The head of the Borgen family, Morten (Henrik Malberg), regularly attends church, but it's a relatively liberal modern congregation, headed by a pastor (Ove Rud), who tries to be forward-thinking: He denies the possibility of miracles in a world in which God has established physical laws, although he doesn't have a ready answer when he's asked about the miracles in the Bible. When Morten's youngest son, Anders (Cay Kristiansen), falls in love with a young woman, her father, Peter (Ejner Federspiel), who belongs to a very conservative sect, forbids her to marry Anders. Then everyone's faith or lack of it is put to test when Inger goes into labor. The doctor (Henry Skjaer) thinks he has saved her life by aborting the fetus -- we are told that it has to be cut into four pieces to deliver it -- but after he leaves, Inger dies. As she is lying in her coffin, Peter arrives to tell Morten that her death has made him realize his lack of charity and that Anders can marry his daughter. And as if this doesn't sound conventionally sentimental enough, the film ends with Inger, who has died in childbirth, being restored to life with the help of Johannes and the simple faith of her young daughter. Embracing Inger, Mikkel now proclaims that he is a believer. The conundrum of faith and evidence runs through the film. For example, if the only thing that can restore one's faith is a miracle, can we really call that faith? What makes Ordet work -- in fact, what makes it a great film -- is that it poses such questions without attempting answers. It subverts all our expectations about what a serious-minded film about religion -- not the phony piety of Hollywood biblical epics -- should be. Dreyer and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen keep everything deceptively simple: Although the film takes place in only a few sparely decorated settings, the reliance on very long single takes and a slowly traveling camera has a documentary-like effect that engages a kind of conviction on the part of the audience that makes the shock of Inger's resurrection more unsettling. We don't usually expect to find our expectations about the way things are -- or the way movies should treat them -- so rudely and so provocatively exploded.

Sunday, June 12, 2016

The Red Mill (Roscoe Arbuckle, 1927)

The Red Mill is a surprisingly well-preserved silent film, with crisp images -- the cinematography is by Hendrik Sartov, a Danish director of photography who also shot La Bohème (King Vidor, 1926) and The Scarlet Letter (Victor Sjöstrom, 1926). It's also a fairly forgettable romantic farce, about Tina (Marion Davies), a Dutch scullery maid, who falls in love with Dennis (Owen Moore), an Irishman visiting Holland, and gets involved with a plot to save Gretchen (Louise Fazenda) from having to marry someone other than her boyfriend Jacop (Karl Dane). The whole thing is very loosely based on a creaky old Victor Herbert operetta. The chief distinction of the film is that it was directed by Roscoe ("Fatty") Arbuckle, who had to take the pseudonym William Goodrich because he had been blacklisted after the scandal over the death of Virginia Rappe -- even though Arbuckle was acquitted. Given that the film is a fitfully amusing comedy, whose chief virtue is that is shows off the great comic gifts of Davies, it might be surprising to find it in such pristine condition when so many other (and better) silent films are available only in patched-together restorations or have been lost altogether. The reason is probably that it was produced by William Randolph Hearst's company, Cosmopolitan Productions, which existed largely to showcase Davies, Hearst's mistress. So MGM, which released the film, took special care not to offend Hearst in its handling of The Red Mill. Davies is, as so frequently, a delight, playing physical comedy without sacrificing her beauty and femininity. She does a wonderful slapstick bit in which she tries to solve the problem of assembling a folding ironing board -- a twist on the familiar struggles of comedians with folding beach chairs. But Arbuckle, who directed dozens of short films, doesn't give this movie the pace needed to sustain itself at feature length. Frances Marion did the screenplay and the cornball captions -- sample: "A summer on Holland's canals leaves an impression, but a fall on its ice leaves a scar" -- are by Joseph Farnham.

Saturday, June 11, 2016

The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin Scorsese, 2013)

Leonardo DiCaprio has replaced Robert De Niro as Martin Scorsese's go-to leading man, but he has yet to make his Raging Bull (1980) or Taxi Driver (1976), which many people -- including me -- think of as the peak achievements of both Scorsese and De Niro. The Wolf of Wall Street comes close to being DiCaprio's GoodFellas (1990). Both movies are based on true stories that illuminate the dark side of American experience: In the case of GoodFellas, the mob, and for Wolf, the unholy pursuit of wealth in the stock market. Both are in large part black comedies, full of sex and drugs, and both end in an inevitable downfall. And both have been criticized for excessively glamorizing the lifestyles of their protagonists. Terence Winter's adaptation of the memoir of Wall Street fraudster Jordan Belfort (DiCaprio) spares no excess in depicting a life corrupted by unchecked greed, and yet neither Winter nor Scorsese seems able to put the course of Belfort's corruption into plausible shape, the way Scorsese and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi made Henry Hill's rise and fall plausible in GoodFellas. It's a flamboyant film, with entertaining and sometimes frightening performances by DiCaprio, Jonah Hill, Margot Robbie, Matthew McConaughey, Jon Bernthal, and Jean Dujardin, but the film often seems to be carried away with its own determination to get away with as much outrageous behavior and language as possible. I would have welcomed a little less Jordan Belfort and a little more Patrick Denham (Kyle Chandler), who was based on Gregory Coleman, the FBI agent who finally managed to bring Belfort down. But as in GoodFellas, the emphasis is less on the law than on the disorder.

The Martian (Ridley Scott, 2015)

Andy Weir's best-selling science fiction novel was one of the few that manage to emphasize science almost as much as fiction. The film version, being aimed at a somewhat less cerebral audience, doesn't quite keep that balance, but Drew Goddard's screenplay is an admirable effort to keep up with protagonist Mark Watney's (Matt Damon) determination to "science the shit out of" the problem of surviving after he has been marooned on Mars. And in an age when science has fallen afoul of politics, The Martian nobly attempts to bring some luster to this essential human endeavor. There is also a political undercurrent in the film, namely the hurdles that NASA administrator Teddy Sanders (Jeff Daniels) has to leap in order to achieve the rescue of his stranded astronaut. It's gratifying, too, to see so many actors of color -- Michael Peña, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Benedict Wong, Donald Glover, among others -- given key roles in the effort to rescue Watney, all of them given parts emphasizing their skill and intelligence. On the other hand, there were protests that the ethnicity of some of the characters in the film had been changed. In the novel, for example, the mission director is called Venkat Kapoor, and he is a Hindu. His first name is changed in the film to Vincent, and he's played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, the British actor whose parents were born in Nigeria -- the change is signaled by an explanation that his father was Hindu and his mother was a Baptist. One reason for such protests is that director Scott's previous film was Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014), in which all of the Egyptian and Middle Eastern characters were played by white actors like Christian Bale and Joel Edgerton, a continuation of an old Hollywood tradition that increasingly seems wrong-headed. Fortunately, in The Martian Scott kept the novel's prominent female roles, including mission commander Melissa Lewis (Jessica Chastain) and astronaut Beth Johanssen (Kate Mara).

Friday, June 10, 2016

No Country for Old Men (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2007)

No Country is not my favorite Coen brothers film; Fargo (1996), Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), Miller's Crossing (1990), and maybe O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) and The Big Lebowski (1998) would have to rank higher. But that only shows what an extraordinary contribution the brothers have made to motion picture history. There are those who task the Coens with too much cleverness, too much awareness of breaking or bending conventions, such as, in this film, dispatching both the protagonist and the antagonist off-screen, depriving us of the catharsis usual in such a thriller. There is, some critics argue, something chilly about the Coens, never letting us get too involved in their characters as potentially real human beings. I'd argue that engaging sympathetic identification with characters is not a sine qua non in art, and that the tendency of writers and directors to do that has led to a lot of sentimental and falsified endings. And anyway, who doesn't feel a sympathetic identification with Marge Gunderson in Fargo, or the Dude in The Big Lebowski, to name two of their greatest characters? (They also happen to be original creations of the Coens, not borrowed from a novel, as the characters in No Country are.) I haven't read the Cormac McCarthy novel, but the film strikes me as a moral fable akin to Chaucer's Pardoner's Tale, with the implacable Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) as the Death figure stalking Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), whose avarice -- though modified by a few virtues, such as bringing a jug of water, albeit too late, to the man he finds dying in the desert -- finally proves his undoing, despite his clever attempts to avoid his fate. We root for Moss because of our common humanity, a trait lacking in the psychotic Chigurh, but it's telling that the story is framed by the point of view of Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), who can only see the story as a manifestation of what is lacking in human beings. Ed Tom thinks it has something to do with the changing times, which is why there seem to be no countries for old men anymore, but I would suggest that the medieval fable analogy overrides Ed Tom's theory: Human beings have always been like this. That said, the Coens seem to be assembling a kind of American collage. One thing that No Country shares with all of the Coens' best movies is a strong sense of time and place, whether it's the frigid Minnesota of Fargo, the Greenwich Village in the '60s of Inside Llewyn Davis, the unspecified Prohibition-era city of Miller's Crossing, the Depression-era Mississippi of O Brother, or the '90s L.A. of The Big Lebowski. In this case, it's West Texas in 1980, and every note struck about place and period has a resemblance to truth, without being literal about it. As usual, the Coens' collaborators -- especially cinematographer Roger Deakins and composer Carter Burwell -- play a major role, especially Burwell's almost subliminal score.

Wednesday, June 8, 2016

Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944)

Laura is a clever spin on Pygmalion, with a Henry Higgins called Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) whose protégée is an Eliza Doolittle called Laura Hunt (Gene Tierney). It's also a spin on the classical myth of Pygmalion, who fell in love with the statue of Galatea he had sculpted, bringing her to life. This Pygmalion is a detective, Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), who falls in love with the portrait of Laura, who he thinks has been murdered, and is startled when she walks through the door, very much alive. Maybe this classical underpinning explains why Laura has become such an enduring classic, but probably it really has to do with a story so well-scripted, by Jay Dratler, Samuel Hoffenstein, and Elizabeth Reinhardt from a novel by Vera Caspary, well-acted by Webb, Tierney, and Andrews, along with Vincent Price as the decadent Shelby Carpenter and Judith Anderson as the predatory Ann Treadwell, and most of all, directed with the right attention to its slyly nasty tone by Otto Preminger, one of the most underrated of Hollywood directors of the 1940s and '50s. Like such acerbic films as The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) and All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950), Laura is full of characters one would be well advised to steer clear of in real life, but who make for tremendous entertainment when viewed on a screen from a safe distance. It makes a feint at a conventional happily romantic ending, with Laura supposedly going off with McPherson, but do we really believe it? Laura Hunt has shown dubious taste in men -- whom McPherson characterizes as "a remarkable collection of dopes"-- including the desiccated fop Waldo and the smarmy kept man Shelby. So it's hard to believe the social butterfly Lydecker has created is going to settle down happily with a man who, as Waldo says once, fell in love with her when she was a corpse and apparently has never had a relationship with a woman other than the "doll in Washington Heights who once got a fox fur outta" him. Laura is notable, too, for its deft evasions of the Production Code, including Laura's hinted-at out-of-wedlock liaisons, which are at the same time undercut by the suggestions that Waldo and Shelby are gay -- another Code taboo. (Shelby, for example, has an exceptional interest in women's hats, including one of Laura's and the one of Ann's that he calls "completely wonderful.") This shouldn't surprise us, as Preminger went on to be one of the most aggressive Code-breakers, challenging its sexual taboos in The Moon Is Blue (1953) and its strictures on the depiction of drug use in The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), and giving the enforcers fits with Anatomy of a Murder (1959). In addition to the contributions to Laura's classic status already mentioned, there is also the familiar score by David Raksin. (Johnny Mercer added lyrics to its main theme after the film was released, creating the song "Laura.") And Joseph LaShelle won an Oscar for the film's cinematography.

Tuesday, June 7, 2016

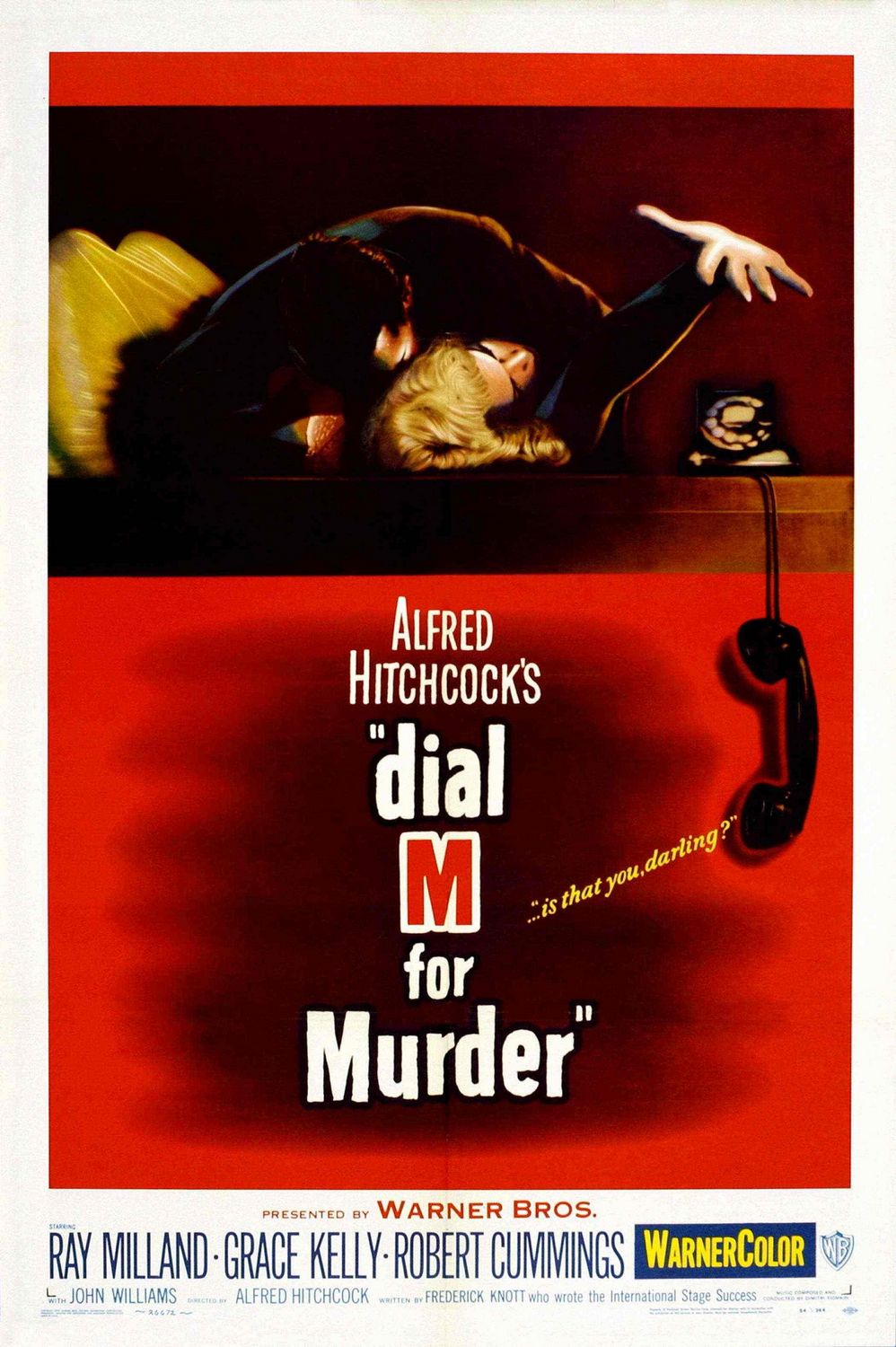

Dial M for Murder (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

It's a measure of how little Hollywood understood what kind of filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was that Warner Bros. insisted he make Dial M for Murder in 3-D. The process was nearing the end of its '50s heyday, one of the several attempts by the troubled studios to draw patrons away from their TV sets and into the theaters. The 3-D films of the '50s, like the blockbusters released in the process today, were mostly filled with things being flung, poked, thrust, or shot at the audience. As Hitchcock had a reputation as a "master of suspense," perhaps the studio assumed that he'd use the process to scare people. But he never needed tricks like 3-D for that, being perfectly skilled at pacing and cutting to build tension in the audience. Dial M ended up being shown mostly in 2-D anyway, and only some very peculiar blocking and framing in its images today show the efforts Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks did to accommodate the moribund process: Scenes are often filmed with table lamps prominent in the foreground, for no other reason than to emphasize the action taking place beyond them. The scene in which Swann (Anthony Dawson) attempts to murder Margot (Grace Kelly) is the only bit of action that would have benefited from the process, with Margot's hand desperately reaching toward the audience for the scissors behind her. Dial M is essentially a filmed play -- Frederick Knott adapted his own theatrical hit for the movies -- and as such relies far more on dialogue and spoken exposition for its narrative coherence. It was the first of three movies -- the other two are Rear Window (1954) and To Catch a Thief (1955) -- that Hitchcock made with Kelly, and the one that gives her least to do in the way of characterization: Mostly she just has to be a pawn moved about by her husband (Ray Milland), her lover (Robert Cummings), and the police inspector (John Williams). But she clearly defined Hitchcock's "type," already partly established in his films with Joan Fontaine and Ingrid Bergman: the so-called "cool blond." Eva Marie Saint, Kim Novak, Tippi Hedren, and Janet Leigh would attempt to fill the role afterward, but never with quite the charisma that Kelly, a limited actress but a definite "presence," achieved for him. Milland is very good as the murderous husband, and Williams is a delight as the inspector who has to puzzle out what's going on with all those door keys. The rather goofy-looking Cummings has never made sense to me as a leading man -- he almost wrecks Saboteur (1942), an otherwise well-made Hitchcock film that might be regarded as one of his best if someone other than Cummings and the bland Priscilla Lane had been cast in the leads. It's not surprising that after his performance in Dial M he went straight into television and his own sitcom.

Monday, June 6, 2016

Rebel Without a Cause (Nicholas Ray, 1955)

Rebel Without a Cause seems to me a better movie than either of the other two James Dean made: East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955) and Giant (George Stevens, 1956). It's less pretentious than the adaptation of John Steinbeck's attempt to retell the story of Cain and Abel in the Salinas Valley, and less bloated than the blockbuster version of Edna Ferber's novel about Texas. And Ray, a director with many personal hangups of his own, was far more in tune with Dean than either Kazan or Stevens, who were shocked by their star's eccentricities. Granted, Rebel is full of hack psychology and sociology, attributing the problems of Jim Stark (Dean), Judy (Natalie Wood), and John "Plato" Crawford (Sal Mineo) to parental inadequacy: Jim's weak father (Jim Backus) and domineering mother (Ann Doran) and paternal grandmother (Virginia Brissac), Judy's distant father (William Hopper) and mother (Rochelle Hudson), and Plato's absentee parents who have left him in care of the maid (Marietta Canty). In fact, Jim and his friends really are rebels without a cause, there being neither an efficient cause -- one that makes them do stupidly self-destructive things -- nor a final cause -- a clear purpose behind their madness. Fortunately, Ray is not as interested in explaining his characters as he is in bringing them to life. Unlike Kazan or Stevens, Ray gives his actors ample room to explore the parts they're playing. There's a loose, improvisatory quality to the scenes Dean, Wood, and Mineo play together, more suggestive of the French New Wave filmmakers than of Hollywood's tightly controlled directors. It's no surprise that both Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were admirers of Ray's work. At the same time, though, Rebel is very much a Hollywood product, with vivid color cinematography by Ernest Haller, who had won an Oscar for his work on Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), and a fine score by Leonard Rosenman. Most of all, though, it has Dean, Wood, and Mineo, performers with an obvious rapport. At one point, for example, Dean puts a cigarette in his mouth backward -- filter on the outside -- and Wood reaches out and turns it around, a bit establishing their intimacy that feels so real that you wonder if it was improvised or developed in performance. (In fact, I noticed the gesture because I had just seen Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend, made ten years earlier, in which Jane Wyman performs the same turning-the-cigarette-around action for Ray Milland several times. Cigarettes are nasty things but they make wonderful props.)

Sunday, June 5, 2016

The Lost Weekend (Billy Wilder, 1945)

If such a thing as conscience could be ascribed to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, it might be said that giving The Lost Weekend and director Billy Wilder the best picture and best director Oscars was an attempt to atone for its failure to honor Wilder's Double Indemnity with those awards the previous year. (The awards went to Leo McCarey and his saccharine Going My Way.) The Lost Weekend is not quite as enduring a film as Double Indemnity: It pulls its punches with a "hopeful" ending, though it should be clear to any intelligent viewer that Ray Milland's Don Birnam is not going to be so easily cured of his alcoholism as he and his girlfriend, Helen St. James (Jane Wyman), seem to think. But the film also lands quite a few of its punches, thanks to Milland's Oscar-winning performance and the intelligent (and also Oscar-winning) adaptation of Charles R. Jackson's novel by Wilder and co-writer Charles Brackett. For its day, still under the watchful eyes of the Paramount front office and the Production Code, The Lost Weekend seems almost unnervingly frank about the ravages of alcoholism, then usually treated more as a subject for comedy than for semi-realistic drama. The Code prevented the film from ascribing Birnam's drinking to an attempt to cope with his homosexuality, but in some respects this can be seen today as a good change made for the wrong reason, since the roots of addiction to alcohol are far more complicated than any simplistic explanation such as self-loathing. The Code was also powerless to prevent Wilder and Brackett from finessing the suggestion that the friendly "bar girl" Gloria (Doris Dowling) is anything but an on-call prostitute. Increasingly, post-World War II films would treat audiences like the adults the Code administration wanted to prevent them from being. Wyman's Helen is a bit too noble in her persistent support of Birnam's behavior -- she moves from ignorance to denial to enabling to self-sacrifice far too swiftly and easily. But in general, the supporting cast -- Phillip Terry as Birnam's brother, Howard Da Silva as the bartender, Frank Faylen as the seen-it-all-too-often nurse in the drunk ward -- are excellent. The fine cinematography is by John F. Seitz. The score, which is laid on a bit too heavily, especially in the use of the theremin to suggest Birnam's aching need for a drink, is by Miklós Rózsa.

Saturday, June 4, 2016

Interstellar (Christopher Nolan, 2014)

All contemporary space travel sci-fi operates in the shadow of 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), and the best you can do -- as Interstellar's Christopher Nolan and co-scenarist Jonathan Nolan do -- is to acknowledge it without imitating it. I think the fact that production designer Nathan Crowley's robots are slab-like (rather than the android designs we're familiar with) is one nod to Kubrick's film. But more to the point is that 2001 and Interstellar are both about human evolution. Kubrick makes the point more economically than Nolan does, without resorting to theories about wormholes and black holes allowing humans to travel beyond the confines of the fixed speed of light in order to discover an escape from the fate of Earth. In Nolan's film, that fate is dire, a world in which food shortages have led to mass starvation and a cultivation of anti-scientific attitudes. In Nolan's not-so-distant future, bright young people are being indoctrinated with what sounds a lot like current dogma in the more backward parts of the United States. (I'm trying not to say Texas here.) The children of former NASA pilot Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) are being told not only that farming is a nobler profession than engineering, but also that the United States faked the Apollo moon landings in order to deceive the Soviet Union into a buildup in space and military technology that would ruin the Soviet economy. Crazier theories have been advanced even in the current presidential election campaign. The trouble with the film is that eventually it has to come back to Earth and provide a rather muddled and disjointed resolution of the crisis it has presented and tried to solve. Meanwhile, the film is also tasked with trying to explicate for a non-scientific audience some cutting-edge theories in physics and cosmology. That necessitates an almost three-hour run time in which the audience is alternately dazzled by special effects and subjected to head-spinning theories. Some very attractive and skilled actors are enlisted in the effort: McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, Michael Caine, Matt Damon, John Lithgow, and Ellen Burstyn among many others. But entertaining as it often is, Interstellar never quite makes it past the point of gee-whiz tinkering with some intriguing ideas into potential classic movie status.

Friday, June 3, 2016

Show Boat (James Whale, 1936)

Productions of Show Boat over the years are almost a barometer of the changes in racial attitudes. In the original 1927 Broadway production, for example, the opening song, "Cotton Blossom," sung by dock workers, contained the line "Niggers all work on the Mississippi." The 1936 film changed the offensive word to "Darkies," which today is only somewhat less offensive, so contemporary performances usually change the line to "Here we all work on the Mississippi." Today, we wince when Irene Dunne as Magnolia appears in blackface to sing "Gallivantin' Aroun'," a number created for the film, and we have to acknowledge that minstrelsy was still prevalent well into the mid-20th century. But Show Boat also presents structural problems. It is front-loaded with its best Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II songs: In the original production, "Make Believe," "Ol' Man River," "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man," "Life Upon the Wicked Stage," and "You Are Love" all appear in Act I, leaving only "Why Do I Love You?" and "Bill" for Act II, among reprises of some of the other songs plus some oldies like "After the Ball." The film doesn't solve that problem: In fact, it omits "Life Upon the Wicked Stage" and "Why Do I Love You?" entirely, except as background music. It replaces them with a few new songs, including "I Have the Room Above You," a duet for Magnolia and Gaylord Ravenal (Allan Jones), and "Ah Still Suits Me," a somewhat too racially stereotyped duet for Joe (Paul Robeson) and Queenie (Hattie McDaniel), but they're still part of the first half of the film. And the plot seems to dwindle off into anticlimax after Gaylord leaves Magnolia. But James Whale's film version is one of the most successful translations of an admittedly imperfect stage musical to the screen. One reason is that it gives us a chance to see two legendary performers, Paul Robeson and Helen Morgan. Robeson's version of "Ol' Man River" is not only splendidly sung, but Whale also gives it a magnificent staging, beautifully filmed by John J. Mescall, that emphasizes the backbreaking toil that Robeson's Joe sings about. Morgan's performance as Julie makes me wish that Kern and Hammerstein had given her more songs, but her "Bill" is extraordinarily touching, and "Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man" becomes, after her introduction, a lively ensemble number for her, Dunne, McDaniel, and Robeson. It's also good to see McDaniel in a role that gives her a chance to sing -- she began her career as a singer. Too bad that Queenie's big number, "Queenie's Ballyhoo," was cut from the film. MGM remade Show Boat in 1951, with Kathryn Grayson as Magnolia, Howard Keel as Gaylord, and Ava Gardner as Julie, under the direction of George Sidney. Lena Horne wanted to play Julie, but the studio chickened out, fearing the reaction in the South. (Gardner's singing was dubbed by Annette Warren.) MGM also tried to suppress the 1936 film, which is vastly superior. Fortunately, it failed.

Thursday, June 2, 2016

The Rules of the Game (Jean Renoir, 1939)

The first time I saw The Rules of the Game, many years ago, I didn't get it. I knew it was often spoken of as one of the great films, but I couldn't see why. I had been raised on Hollywood movies, which fell neatly into their assigned slots: love story, adventure, screwball comedy, satire, social commentary, and so on. Jean Renoir's film seemed to be all of those things, and none of them satisfactorily. I had to be weaned from narrative formulas to realize why this sometimes madcap, sometimes brutal tragicomedy is regarded so highly. And I had to learn why the period it depicts, the brink of World War II, isn't just a point in the rapidly receding past, but the emblematic representation of a precipice that the human world always seems poised upon, whether the chief threat to civilization is Nazism or global climate change. The Rules of the Game is about us, dancing merrily on the brink, trying to ignore our mutual cruelty and to deny our blindness. Renoir's characters are blinded by lust and privilege, and they amuse us until they do horrible things like wantonly slaughter small animals or play foolish games whose rules they take too lightly. I'm afraid that makes one of the most entertaining (if disturbing) films ever made seem like no fun at all, but it should really be taken as a warning never to ignore the subtext of any work of art. Much of the film was improvised from a story Renoir provided, to the glory of such performers as Marcel Dalio as the marquis, Nora Gregor as his wife, Paulette Dubost as Lisette, Roland Toutain as André, Gaston Modot as Schumacher, Julien Carette as Marceau, and especially Renoir himself as Octave. Renoir's camera prowls relentlessly, restlessly through the giddy action and the sumptuousness of the sets by Max Douy and Eugène Lourié. It's not surprising that one of Renoir's assistants was the legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. And, given my own initial reaction to the film, it's also not surprising that The Rules of the Game was a critical and commercial flop, trimmed to a nubbin of its original length, banned by the Vichy government, and after its negative was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1942, potentially lost forever. Fortunately, prints survived, and by 1959 Renoir's admirers had reassembled it for a more appreciative posterity.

Wednesday, June 1, 2016

The Lower Depths (Akira Kurosawa, 1957)

|

| Bokuzen Hidari in The Lower Depths |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)

_poster.jpg)