A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

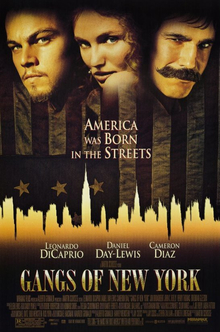

Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)

Gangs of New York is such a sprawling, unfocused movie that I can almost imagine the filmmakers throwing up their hands and sighing, "Well, at least we've got Daniel." Because Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Bill "The Butcher" Cutting holds the film together whenever it tends to sink into the banality of its revenge plot or to wander off into the eddies of New York City history. A historical drama like Gangs of New York needs two things: a compelling central story and an audience that knows something about the history on which it's based. But for all their violence and their anticipation of problems that continue to manifest themselves in the United States, the Draft Riots of 1863 and the almost two decades of gang wars that led up to them are mostly textbook footnotes to most Americans. Director Martin Scorsese's determination to depict them led to the hiring of a formidable team of screenwriters -- Jay Cocks, who wrote the story, and Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, who collaborated with Cocks on the screenplay. Unfortunately, the narrative thread that they came up with is tired. As a boy, Amsterdam Vallon saw his father, an Irish Catholic nicknamed "Priest" (Liam Neeson), cut down by Bill the Butcher in a huge battle between the Irish immigrant gang, the Dead Rabbits, and Bill's Protestant gang, the Natives. Sixteen years later Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio) returns to the Five Points neighborhood determined to get revenge on Bill, who has managed to make peace with many of the old members of Vallon's father's gang and to become a power-player aligned with Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent). Vallon is introduced to Bill's criminal enterprise by an old boyhood friend, Johnny (Henry Thomas), and he begins to fall under Bill's spell -- along with that of a pretty pickpocket, Jenny Everdeane (Cameron Diaz). But the relationship between Vallon and Jenny stirs the jealousy of Johnny, who is smitten with her, and he reveals to Bill that Vallon is the son of his old enemy, leading to a climactic showdown -- one that just happens to occur simultaneously with the Draft Riots. There's a lot of good stuff in Gangs of New York, including Michael Ballhaus's cinematography and Dante Ferretti's production design -- the sets were constructed at Cinecittà Studios in Rome. But the awkward attempt to merge the romantic revenge plot with the historical background shifts the focus away from what the film is supposedly about: racism, anti-immigrant nativism, political corruption, and exploitation of the poor. "You can always hire one half of the poor to kill the other half," Tweed says. Oddly (and sadly), Gangs of New York seems more relevant today than it did in 2002, when the country was recovering from the 9/11 attacks. Then, the Oscar-nominated anthem by U2, "The Hands That Built America," which concludes the film seemed to promise a spirit of unity, an affirmation that the country had overcome the antagonisms depicted in the movie. Today it has a far more ironic effect.

Monday, February 27, 2017

Y Tu Mamá También (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001)

|

| Gael García Bernal in Y Tu Mamá También |

Julio Zapata: Gael García Bernal

Tenoch Iturbide: Diego Luna

Narrator: Daniel Giménez Cacho

Silvia Allende de Iturbide: Diana Bracho

Diego "Saba" Madero: Andrés Almeida

Ana Morelos: Ana López Mercado

Manuel Huerta: Nathan Grinberg

Maria Eugenia Calles de Huerta: Verónica Langer

Cecilia Huerta: Maria Aura

Alejandro "Jano" Montes de Oca: Juan Carlos Remolina

Chuy: Silverio Palacios

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Screenplay: Carlos Cuarón, Alfonso Cuarón

Cinematography: Emmanuel Lubezki

Production design: Marc Bedia, Miguel Ángel Álvarez

Film editing: Alfonso Cuarón, Alex Rodríguez

Alfonso Cuarón's Y Tu Mamá También is kept aloft for so long by wit and energy, and by the skills of its actors, director, and cinematographer, that it's a disappointment to consider the way it deflates a little at the end. It is, on the whole, a brilliant transfiguration of several well-worn genres: the teen sex comedy, the road movie, the coming-of-age fable. Cuarón has credited Jean-Luc Godard's Masculin Féminin (1966) as a major inspiration, but I think it owes as much to François Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962), not least in Daniel Giménez Cacho's superbly ironic voiceover narrator, who provides a larger context for the actions of the three main characters. It's the narrator, for instance, who tells us that the traffic jam that holds up our middle-class teenagers was caused by the death of a working man who tried to cross the freeway because otherwise he would have had to walk a mile and a half out of his way to use the only crossing bridge. Or that Chuy, the fisherman who befriends the trio when they finally reach the secluded beach, will lose his livelihood to developers and commercial fisheries and wind up as a janitor in an Acapulco hotel. Somehow, Cuarón manages to avoid heavy-handedness with these comments, injecting the necessary amount of serious social commentary into a story about two horny Mexico City teenagers and the older woman who goes in search of a beach called "Heaven's Mouth" with them. Even in the story, the subtext of social class in contemporary Mexico keeps peeking through: There's a slight tension between the upper-middle-class Tenoch, whose father is a government official, and the lower-middle-class Julio that's suggestive of Tenoch's sense of privilege. Similarly, Luisa, who was trained as a dental technician, confesses to a sense of inferiority to her husband, Jano, Tenoch's cousin, and his better-educated friends. The screenplay by Cuarón and his brother, Carlos, deserved the Oscar nomination it received for these attempts to provide a deep backstory for the characters. Even so, the film owes much to the obvious rapport between Luna and García Bernal, and to the steady centering influence of Verdú, all of whom participated in rehearsals that were often improvisatory embroidering on the Cuaróns's screenplay. Cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who would go on to receive three consecutive Oscars for much showier work on Cuarón's Gravity (2013) and on Alejandro Iñárritu's Birdman (2104) and The Revenant (2015), here maintains a strictly documentary style of camerawork, though often with the subtle use of long takes and wide-angle lenses. As I said, I think the film deflates a bit at the end with the revelation of Luisa's death: It seems an unnecessary attempt to moralize, to provide a motive -- knowing that she has terminal cancer -- for her running away and having sex with the boys, turning it into only a final fling. Would we think less of Luisa if she were simply asserting her right to be as pleasure-driven as her philandering husband? Were the Cuaróns attempting to obviate slut-shaming by giving Luisa cancer? I hope not, because the film shows such intelligence and sensitivity otherwise.

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Tomorrow (Joseph Anthony, 1972)

|

| Olga Bellin and Robert Duvall in Tomorrow |

Saturday, February 25, 2017

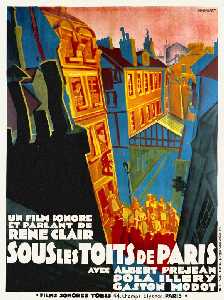

Under the Roofs of Paris (René Clair, 1930)

Under the Roofs of Paris, writer-director René Clair's sometimes shaky but often charming bridge between silent films and talkies, begins with cinematographer Georges Périnal's lovely crane shot that slowly descends from the rooftops of Paris -- actually the rooftops of art director Lazare Meerson's elaborate and ingenious set -- to the street where song-plugger Albert (Albert Préjean) is conducting a singalong of "Sous les Toits de Paris," the film's French title song, trying to sell copies of the sheet music. As the camera pans around the crowd, we meet several more characters prominent in the film: the thief Émile (Bill Bocket), who is carefully lifting small valuables from women's purses; the dandyish gangster Fred (Gaston Modot); and a pretty young Romanian woman, Pola (Pola Illéry), who becomes a target for both Émile's thievery and Fred and Albert's attentions. Albert is a success at selling the song, as we see in a vertical pan up the façade of an apartment building, from each window of which comes the sound of someone singing it. This beautiful shot demonstrates how quickly Clair, a reluctant convert, caught on to the innovations possible in sound films. It may have influenced Rouben Mamoulian's brilliant montage in Love Me Tonight (1932), which tracks from Maurice Chevalier singing "Isn't It Romantic?" in his Paris tailor shop as the song spreads across country to Jeanette MacDonald singing it in her château. But Clair also displays some of the uncertainty of silent filmmakers in his dialogue scenes, which have the curious sluggish pace found in early talkies whose directors haven't figured out the rhythm of scenes that aren't interrupted by intertitles. In fact, Clair uses synchronized dialogue sparingly: There are a lot of scenes in which we don't hear what characters are saying, sometimes because the music in the bar where they're talking is too loud, and sometimes because we're viewing them through windows and glass doors. Much of the film uses familiar silent storytelling techniques -- to good effect. The story deals with Albert's ill-fated love for Pola, which develops when Fred steals her house key, making it necessary for her to spend the night (chastely and comically) in Albert's apartment. But then Albert is caught with some of Émile's loot -- the thief has stashed it in Albert's room -- and sent to jail. During his absence, Pola falls for Albert's friend Louis (Edmond T. Gréville), leaving things to be resolved at the film's bittersweet end, when the camera tracks away from Albert plugging a new song back up to the rooftops. The film plays on a characteristic fascination with Parisian lower-class life that includes slumming well-dressed upper-class types dropping in on the dives to see how the other half lives -- a motif that recurs in other French films set in the Paris underworld, like Jacques Becker's Casque d'Or (1952).

Friday, February 24, 2017

Brute Force (Jules Dassin, 1947)

Surprisingly violent for a film made under the Production Code, Brute Force gives us a prison-break story in which we root for the prisoners, but it still comes down heavily on the crime-does-not-pay moral: "Nobody escapes," says one of the movie's few survivors to the camera at the end. "Nobody ever really escapes." Under Jules Dassin's direction, Richard Brooks's screenplay tries to have it both ways: The cons are heroic and the guards are villainous, but law and order must prevail. The easy way out of this is to kill off both the heroes and the villains. The chief hero is Joe Collins, played by Burt Lancaster with his usual handsomely bullish intensity. The chief villain is the head guard, Capt. Munsey, played against type by Hume Cronyn. The imbalance between the two is exhibited early in the film when Munsey tries to dress down Collins but is confronted with a massive Lancastrian cold shoulder. But Munsey has guile on his side, along with ambition to supplant the weakling Warden Barnes (Roman Bohnen), who is under political pressure to toughen up enforcement in the prison, from which reports of unrest among the inmates have been emerging. Dassin tells us all we need to know about Munsey when we see him in his office, which has little homoerotic touches in its decor like a picture of a male torso, along with a large Hitlerian photograph of Munsey himself. While beating a prisoner with a rubber hose to elicit information about a planned prison break, Munsey turns up the volume on the Wagner he is playing on the phonograph. Not that the cons are any less gentle: To punish a prisoner who collaborated with the guards, they force him into the machine that stamps out license plates, and during the climactic prison break, a stoolie is strapped to the front of a mine car and shoved out into the gunfire from the guards. The film never really lightens things up, though there are some flashback scenes involving tender moments between some of the prisoners and what the credits bill as "the women on the 'outside,'" including Ann Blyth as Collins's cancer-stricken wife. There are some good performances from Charles Bickford as the con who edits the prison newspaper and joins the escape plan after he learns that his expected parole has been put on indefinite hold, and Art Smith as the prison's cynical, alcoholic doctor, along with solid support from Sam Levene, Jeff Corey, Howard Duff, and a horde of well-chosen ugly-mug extras.

Thursday, February 23, 2017

Eat Drink Man Woman (Ang Lee, 1994)

|

| Yu-Wen Wang, Chien-Lien Wu, and Kuei-Mei Yang in Eat Drink Man Woman |

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

The Grapes of Wrath (John Ford, 1940)

Did Tom Joad's descendants vote for Donald Trump? Do Marfa Lapkina's support Vladmir Putin? John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath begins with a tractor pushing people from the land they've worked, while The Old and the New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov, 1929) ends with a tractor helping people harvest their crops. It's just coincidence that I watched two movies about oppressed farm laborers on consecutive nights, but the juxtaposition set me thinking about the ways in which movies lie to us about matters of politics, history, and social justice (among other things). In both cases, a core of truth was pushed through filters: in Eisenstein's, that of the Soviet state, in Ford's that of a Hollywood studio. So in the case of The Old and the New we get a fable about the wonders of collectivism and technology, whereas in The Grapes of Wrath we get a feel-good affirmation of the myth that "we're the people" and that we'll be there "wherever there's a fight, so hungry people can eat." Both films are good, but neither, despite many claims especially for The Grapes of Wrath, is great, largely because their messages overwhelm their medium. Movies are greatest when they immerse us in people's lives, thoughts, and emotions, not when they preach at us about them. It's what makes William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying a greater novel than John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. Both are superficially about the odysseys of two poor white families, but Faulkner lets us live in and with the Bundrens while Steinbeck turns the Joads into illustrated sociology. Ford won the second of his record-setting four Oscars for best director for this film, and it displays some of his strengths: direct, unaffected storytelling and a feeling for people and the way they can be tied to the land. It has some masterly cinematography by Gregg Toland and a documentary-like realism in the use of settings along Route 66. The actors, including such Ford stock-company players as John Carradine, John Qualen, and Ward Bond, never let Hollywood gloss show through their rags and stubble -- although I think the kids are a little too clean. Nunnally Johnson's screenplay mutes Steinbeck's determination to go for the symbolic at every opportunity -- we are spared, probably thanks for once to the censors, the novel's ending, in which Rosasharn breastfeeds an old man. But there's a sort of slackness to the film, a feeling that the kind of exuberance of which Ford was capable in movies like Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956) has been smothered under producer Darryl F. Zanuck's need to make a Big Important Film. I like Henry Fonda in the movie, but I don't think he's ever allowed to turn Tom Joad into a real character; it's as if he spends the whole movie just hanging around waiting to give his big farewell speech to Ma (Jane Darwell, whose own film-concluding speech won her an Oscar).

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

The Old and the New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov, 1929)

Sergei Eisenstein's last silent film almost deserves the old joke that you can always tell a Soviet film because the hero is a tractor. The Old and the New (sometimes called Old and New; the Russian language has no definite or indefinite articles) does conclude with a kind of ballet of tractors, but its hero is human: Marfa Lapkina, an actual Russian peasant who essentially plays herself in a story about the efforts to organize a kolkhoz, a collective farm. We first see Marfa struggling to survive as a farmer who doesn't even have a horse. Reduced to begging, she goes to the fat, greasy kulaks in her neighborhood, who reject her pleas for help. But a revolutionary organizer arrives in the village to set up a collective and introduce the locals to farm machinery. The rest of the film depicts Marfa's rise to leadership of the collective, battling the resistance of stick-in-the-muds, kulaks who poison the collective's bull, and bureaucrats who drag their feet on providing the collective with a tractor. The film was begun in 1927 under the title The General Line, but Eisenstein's work on it was interrupted so he could finish October (Ten Days That Shook the World), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. Meanwhile, Leon Trotsky, whose ideas about collective agriculture were the original impetus for the film, fell from power -- a foreshadowing not only of the difficulties Eisenstein was to have dealing with Soviet ideology as Stalin consolidated his power, but also of the troubles ahead for Russian farmers in the 1930s. The film was taken out of Eisenstein's hands and re-edited, but the restored version we have today is visually fascinating: The opening scenes of suffering Russian peasants, strikingly filmed by Eduard Tisse, bring to mind the work of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange in documenting American farmers in the South and the Dust Bowl during the Depression. There are several bravura montages, some of which are used for a comic effect we don't usually expect from Eisenstein, such as the "wedding scene" in which the bride turns out to be the collective's cow and the groom the bull, and the demonstration of a new milk separator that builds to an orgasmic release of cream from the machine's lovingly filmed spigots. But the propaganda is also thick and heavy in the depiction of kulaks and bureaucrats, and especially in the treatment of the Orthodox church in a scene in which an ecclesiastical procession goes out to pray for rain to end the drought. The images of the sweaty clergy and congregants carrying icons and prostrating themselves in supplication are intercut with images of bleating sheep. Eisenstein left the Soviet Union, accompanied by Tisse and his co-director Girgori Aleksandrov, in 1928; after a disastrous attempt to work in the United States and Mexico, he was persuaded to return to Russia in 1932 but didn't complete another film until Alexander Nevsky in 1938.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Svengali (Archie Mayo, 1931)

|

| Marian Marsh, Bramwell Fletcher, and John Barrymore in Svengali |

Trilby O'Farrell: Marian Marsh

The Laird: Donald Crisp

Billee: Bramwell Fletcher

Madame Honori: Carmel Myers

Gecko: Luis Alberni

Monsieur Taffy: Lumsden Hare

Bonelli: Paul Porcasi

Director: Archie Mayo

Screenplay: J. Grubb Alexander

Based on a novel by George L. Du Maurier

Cinematography: Barney McGill

Art direction: Anton Grot

Film editing: William Holmes

Music: David Mendoza

George Du Maurier's 1894 novel was called Trilby, as were many of the stage adaptations and early silent film versions. But if you cast John Barrymore as the sinister hypnotist, you almost have to call your film Svengali. It's one of Barrymore's juiciest movie performances, but it surprisingly didn't earn him an Oscar nomination -- an honor he never received. To add to the irony, the best actor Oscar that year went to his brother Lionel for A Free Soul (Clarence Brown, 1931), and one of the actors who did receive a nomination was Fredric March for playing Tony Cavendish, an obvious caricature of John Barrymore, in The Royal Family of Broadway (George Cukor and Cyril Gardner, 1930). Though Barrymore's Svengali doesn't particularly deserve an award, it's the best thing about the film aside from the sets by Anton Grot that were influenced by German expressionism and did earn Grot a nomination, as did cinematographer Barney McGill's filming of them. Like many early talkies, Svengali is slackly paced, as if director Archie Mayo, who learned his craft in the silent era, was still slowing things down so title cards could be placed at the appropriate intervals. It also has some problems of tone: Svengali is not quite the sinister monster you expect him to be from his reputation as an archetype of masterful control. In the beginning he's the butt of horseplay from some of his fellow Paris bohemians, the painters known as The Laird and Taffy, who decide he doesn't bathe often enough and dump him into a bathtub. We know his potential for evil after he causes Madame Honori to commit suicide, but even her character is played for comedy before her untimely end. In this adaptation, by J. Grubb Alexander, the plot revolves around Svengali's manipulation of Trilby, an artist's model whose potential as a singer -- even though she can't quite carry a tune -- he deduces from the shape of her mouth. He uses his hypnotic powers to turn her into a diva, though the one performance we see from her, a bit of the Mad Scene from Lucia di Lammermoor, doesn't merit the ovation it receives -- perhaps he hypnotized the audience, too. But control of Trilby comes at a cost: Svengali's health begins to decline, and Trilby's career along with it, until at the end they both die as she performs in a nightclub in Cairo, second-billed to a troupe of belly-dancers. Only the lovestruck young artist known as "Little Billee," who has devoted his life to tracking Trilby in hopes of winning her back, is there to witness her end. Thanks to Barrymore, and some good support from character actors like Luis Alberni, who plays Svengali's assistant with the improbable name Gecko, Svengali is never unwatchable, and it mostly avoids the antisemitic notes that many have observed in the character, who is said to have mysterious origins, perhaps in Poland, in the novel and its adaptations.

Sunday, February 19, 2017

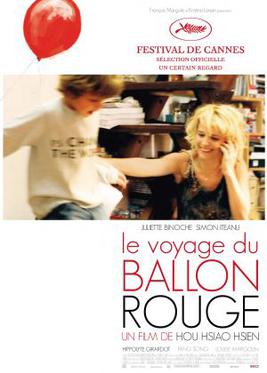

Flight of the Red Balloon (Hou Hsiao-Hsien, 2007)

The Red Balloon (Albert Lamorisse, 1956) is a short film that won the Oscar for best original screenplay, even though it's only a little over half an hour long and has only a few lines of spoken dialogue. In it, a boy (writer-director Lamorisse's young son, Pascal) on his way to school finds a large red balloon that has become caught in a lamppost. He soon discovers that he can't take the balloon with him on a bus or into his school, but the balloon is waiting for him after classes. He's also forbidden to bring the balloon into his home, but it floats up to his bedroom window and he lets it in. Over the next couple of days, the balloon tags along, sometimes getting the boy into trouble, until it's finally punctured by a rock fired from another boy's slingshot and slowly dies. Whereupon balloons from all over Paris flock to the boy, who gathers them and floats away over the rooftops. It's a small charmer, with ravishing views of 1950s Paris by cinematographer Edmond Séchan. The balloon becomes emblematic of childhood innocence in conflict with the daily grind of adulthood, which is why I think it still strikes a chord with audiences and, in the case of Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-Hsien, inspired an hommage: The Voyage of the Red Balloon. Hou's film, which he co-wrote with François Margolin, is nearly four times the length of Lamorisse's and doesn't have such a neatly symbolic resolution. In it, a boy, Simon (Simon Iteanu), lives with his mother, Suzanne (Juliette Binoche), in a cramped Paris apartment. Suzanne is a puppeteer -- a profession that links her with childhood -- who hires a Chinese film student, Song (Fang Song), as a part-time nanny for Simon. Song is working on her own homage to The Red Balloon, and we see bits of it as she poses Simon with a balloon and films it floating around the city. But much of Hou's film deals with the domestic turmoil that surrounds Simon as Suzanne, a divorcee, tries to cope with juggling career and household problems. She leases part of the building to Marc (Hippolyte Girardot), who has been stiffing her on the rent and tends to pop into her apartment at odd times to use her kitchen and leave it a mess. She is trying to evict him so she'll have a place for her daughter, who lives with Suzanne's ex-husband in Brussels, to stay when she comes to Paris in the summer. Simon patiently endures his mother's frazzled nerves and finds a companion in Song, who quietly manages to bring a little order into the household. By film's end, nothing is really resolved in their lives, but a red balloon peeps into the apartment windows and floats above the skylight over Simon's bed, as if childhood has persisted for the time being against all the assaults against it. It's a poetic, meditative kind of film that gains its strength from immersing us into the lives of others. It seems to me to stretch out a little longer than it should, but it features another terrific performance by Binoche.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

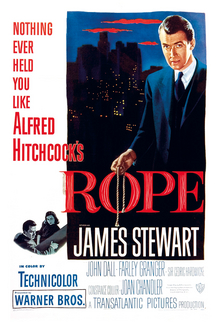

Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

Montage, the assembling of discrete segments of film for dramatic effect, is what makes movies an art form distinct from just filmed theater. Which is why it's odd that so many filmmakers have been tempted to experiment with abandoning montage and simply filming the action and dialogue in continuity. Long takes and tracking shots do have their place in a movie: Think of the suspense built in the opening scene in Orson Welles's Touch of Evil (1958), an extended tracking shot that follows a car with a bomb in it for almost three and a half minutes until the bomb explodes. Or the way Michael Haneke introduces his principal characters with a nine-minute traveling shot in Code Unknown (2000). Or, to consider the ultimate extreme of anti-montage filmmaking, the scenes in Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975), in which the camera not only doesn't move for minutes on end, but characters also walk out of frame, leaving the viewer to contemplate only the banality of the rooms in which the title character lives her daily life. But these shots are only part of the films in question: Eventually, Welles and Haneke and even Akerman are forced to cut from one scene to another to tell a story. Alfred Hitchcock was intrigued with the possibility of making an entire movie without cuts. He couldn't bring it off because of technological limitations: Film magazines of the day held only ten minutes' worth of footage, and movie projectors could show only 20 minutes at a time before reels needed to be changed. In Rope, Hitchcock often works around these limitations by artificial blackouts in which a character's back fills the frame to mask the cut, but he sometimes makes an unmasked quick cut to a character entering the room -- a kind of blink-and-you-miss-it cut.* But for most of the film, we are watching the action in real time, as we would on a stage. Rope began as a play, of course, in 1929, when Patrick Hamilton's thinly disguised version of the 1924 Leopold and Loeb murder case was staged in London. Hitchcock, who had almost certainly seen it on stage, asked Hume Cronyn to adapt it for the screen and then brought in Arthur Laurents to write the screenplay. To accomplish his idea of filming it as a continuous action, he worked with two cinematographers, William V. Skall and Joseph A. Valentine, and a crew of camera operators whose names are listed -- uniquely for the time -- in the opening credits, developing a kind of choreography through the rooms, designed by Perry Ferguson, that appear on the screen. The film opens with the murder of David Kentley (Dick Hogan) by Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger), who then hide his body in a large antique chest and proceed to hold a dinner party in the same room, serving dinner from the lid of the chest, which they cover with a cloth and on which they place two candelabra. The dinner guests are David's father (Cedric Hardwicke), his aunt (Constance Collier), his fiancée, Janet (Joan Chandler), his old friend and rival for Janet's hand (Douglas Dick), and the former headmaster of their prep school, Rupert Cadell (James Stewart). Everyone spends a lot of time wondering why David hasn't shown up for the party, too, while Brandon carries on some intellectual jousting with Rupert and the others about whether murder is really a crime if a superior person kills an inferior one, and Philip, jittery from the beginning, drinks heavily and starts to fall to pieces. Murder will out, eventually, but not after much talk and everyone except Rupert, who returns to find a cigarette case he pretends to have lost, has gone home. There is one beautifully Hitchcockian scene in the film, in which the chest is positioned in the foreground, and while the talk about murder goes on off-camera, we watch the housekeeper (Edith Evanson) clear away the serving dishes, remove the cloth and candelabra, and almost put back the books that had been stored in the chest. It's a rare moment of genuine suspense in a film whose archness of dialogue and sometimes distractingly busy camerawork saps a lot of the necessary tension, especially since we know whodunit and assume that they'll get caught somehow. Some questionable casting also undermines the film: Stewart does what he can as always, but is never quite convincing as a Nietzschean intellectual, and Granger's disintegrating Philip is more a collection of gestures than a characterization. The gay subtext of the film emerges strongly despite the Production Code, but today portrayals of gay men as thrill-killers only adds something of a sour note, even though Dall and Granger were both gay, and Granger was for a time Laurents's lover.

*Technology has since made something like what Hitchcock was aiming for in Rope possible. Alexander Sokurov's 2002 Russian Ark consists of a single 96-minute tracking shot through the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg as a well-rehearsed crowd of actors, dancers, and extras re-create 300 years of Russian history. Projectors today are also capable of handling continuous action without the necessity of reel-changes, making possible Alejandro Iñárruitu's Oscar-winning Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014), with its appearance of unedited continuity, though Iñárritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki resorted to masked cuts very much like Hitchcock's.

*Technology has since made something like what Hitchcock was aiming for in Rope possible. Alexander Sokurov's 2002 Russian Ark consists of a single 96-minute tracking shot through the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg as a well-rehearsed crowd of actors, dancers, and extras re-create 300 years of Russian history. Projectors today are also capable of handling continuous action without the necessity of reel-changes, making possible Alejandro Iñárruitu's Oscar-winning Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014), with its appearance of unedited continuity, though Iñárritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki resorted to masked cuts very much like Hitchcock's.

Friday, February 17, 2017

Downhill (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927)

I'd like to be able to make some cogent comparisons of this silent film directed by Alfred Hitchcock to the sound films I've watched recently, but aside from reinforcing the often-made point that his work in the silent era taught him the valuable lesson that showing is better than telling, there's not much of a link between Downhill and Vertigo (1958), Rear Window (1954), or Psycho (1960). Downhill (retitled When Boys Leave Home for its American release) is a standard melodrama about the calamity brought upon a schoolboy by a shopgirl's accusation and the promise he made that prevents him from revealing the truth. Roddy Berwick (Ivor Novello) is a rich young man whose roommate, Tim Wakeley (Robin Irvine), a student attending the school on a scholarship, gets a shopgirl, Mabel (Annette Benson), in what they used to call "trouble." (Or so she supposedly says: No intertitles explicitly reveal the nature of her accusation.) But Mabel pins the blame on Roddy because his family has money. Roddy nobly takes the rap, promising not to reveal the truth because Tim would lose his scholarship. The sequence that sets up the premise for the rest of the film is slow, overlong, and made a bit murkier than it should be by Hitchcock's refusal to use intertitles. But once Roddy leaves school in disgrace and is kicked out by his father (Norman McKinnel), the film picks up the pace. (It's also something of a break for Novello, who was in his mid-30s when the film was made, a bit old to convincingly play a schoolboy.) The first really Hitchcockian touch in the film comes when we find the disgraced Roddy as a waiter, serving a couple at a table in a cafe. The woman leaves her cigarette case behind, and Roddy slips it into his pocket. Has he fallen so far that he now resorts to larceny? No, the camera angle shifts, and we suddenly find that we are onstage. Roddy is a member of the chorus of a musical comedy, and he has taken the case so he can return it to the star of the show, Julia Fotheringale (Isabel Jeans), with whom he is smitten. It's a witty bit of staging that shows the hand of the master. Suffice it to say, things do not go well for Roddy: He inherits a small fortune from his godmother, which makes him an easy mark for the golddigging Julia, whom he marries and who bankrupts him. He becomes a gigolo in a Montmartre dance hall, and declines further until we find him, dissipated and ill, in a Marseilles rooming house. His fortunes take a turn when some sailors, scheduled for trip to England, decide that his family must have money and take him along to collect a reward for returning him. So Roddy makes his way home and is welcomed by his father, who, having learned the truth, has been searching for him all this time. This rather soppy stuff was devised by Novello himself for a play he co-wrote with Constance Collier under the pseudonym David L'Estrange. It was adapted into a scenario by Eliot Stannard, a frequent collaborator with Hitchcock in the silent era. Though the film is on the whole a dud, there are a few moments of brilliance, particularly a stunning scene when a patron in the dance hall suffers some kind of attack and the waiters draw back the curtains to let in fresh air. The morning light floods the hall, revealing the shabbiness of the locale and its aging, over-made-up customers. The scenes in the squalid Marseilles house are also beautifully illuminated by cinematographer Claude L. McDonnell. And those who know of Hitchcock's fear of policemen will relish the first sight Roddy has when he reaches England at the end: a stern-looking bobby patrolling the harbor.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

I think the most Hitchcockian moment in Psycho is the scene in which Norman disposes of the evidence by sinking Marion Crane's Ford in the swamp with her body and the slightly less than $40,000 she stole in its trunk. We watch as the car slowly settles into the murk with a comically disgusting blurping sound. And then it stops, and we watch Norman's face as he anxiously bites his lip. But just as he is starting out to see if he can help sink it farther, the blurping noise returns and the car sinks to the depths. Who doesn't feel Norman's anxiety and relief in that scene, even though he's a psychotic murderer? This trick of alienating viewers from their own moral values is essential to the greatness of Alfred Hitchcock. On the other hand, I used to think that the least Hitchcockian moment in the film was the psychiatrist's long-winded explanation of Norman's dual-personality disorder, which tells us nothing that we don't already know. But now I think it's a bit of masterstroke. Simon Oakland's performance as the psychiatrist is so florid and self-satisfied that it reveals the character as a pompous showboater, which only heightens the cool, ironic smugness of Norman/Mother in the film's chilling final moment. He/she wouldn't hurt a fly, indeed. What is there to say about Psycho otherwise? That Anthony Perkins is nothing short of brilliant as Norman? Of course. That Janet Leigh's Marion is so well-crafted that we wish she'd been given roles this good throughout her career as a mostly decorative actress? Yes. That Bernard Herrmann deserved all the Oscars he never got for his work on Hitchcock's films? His score for Psycho, for which Hitchcock rewarded Herrmann with a screen credit just before his own as director, didn't even get a nomination -- but then, neither did his scores for The Trouble With Harry (1955), The Wrong Man (1956), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and Marnie (1964). For that matter, Psycho didn't receive a nomination for George Tomasini's film editing, despite the shower scene, a literal textbook example of the art. (That the scene had been storyboarded -- perhaps with the aid of graphic designer Saul Bass, who later even claimed that he had directed it -- doesn't deny the fact that someone, namely Tomasini, had to lay hands on the actual film.) Yet Psycho remains one of the inexhaustible movies, those in which you see something new and different at each viewing, even if it's only to add to your stock of trivia. This time, for example, I was struck by the fact that one of the cops guarding Norman at the end looked vaguely familiar. I checked, and he was played by Ted Knight -- The Mary Tyler Moore Show's Ted Baxter. How can you not love a film that provides revelations like that?

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Certified Copy (Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

In the middle of Certified Copy, just after the film has taken a startling narrative turn, we see a man apparently angrily berating his wife. It looks like a correlative to the tensions that seem to be building between the film's protagonists, the unnamed woman who is labeled Elle in the screenplay (Juliette Binoche) and the writer James Miller (William Shimell). But then the man turns slightly and we see that his tirade is actually directed at someone he's talking to on his mobile phone. When our protagonists talk to the man and the woman, they turn out to be an affectionate couple. (The man is played by the celebrated screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, the woman by Agate Natanson.) Nothing is what it seems in Certified Copy, of course, but if you've watched any of Abbas Kiarostami's films, you're probably ready to be tricked or tantalized. That "startling narrative turn" I mentioned above completely changes our assessment of Elle and James, who begin the film as apparent strangers to each other, and then at mid-film start apparently pretending to be a married couple who, by the end of the film, are supposedly revisiting the scene of their honeymoon 15 years earlier. The pivotal scene in Certified Copy takes place in a cafe in Lusignano, where James steps outside to take a phone call. The owner's wife (Gianna Giachetti) assumes that Elle and James are a married couple and asks why they speak English with each other, since she's French. Elle doesn't set the woman straight about their relationship, and there is a sudden break in which the woman's back is turned to the camera and she whispers something we don't hear to Elle. Then, when James returns, they pretend to be (or become?) the married couple, and he speaks to her in French. There are a few tantalizing hints that they may in fact be a long-married couple reuniting after a separation, having pretended at the start of the film to be strangers to each other. There is an equally strong suggestion that they may be strangers who have discovered a mutual love of role-playing. Or there is a third possibility, that the film depict two actualities: i.e., that its first half depicts one couple and its second half the other. If so, Certified Copy resembles Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch, 2001), with its unexplained mid-film narrative disjunction, more than it does the other films about enigmatic relationships or disintegrating marriages to which it has frequently been compared: Journey to Italy (Roberto Rossellini, 1953), L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960), and Last Year in Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961). The title of the film refers to the book James has written about art, in which he argues that the distinction between an "original" work of art and a copy of it is irrelevant. Consequently, Kiarostami, who wrote the screenplay with Caroline Eliacheff, plays with duplicates and mirrors throughout the film, with the help of cinematographer Luca Bigazzi. There is, for example, a wonderfully tricky shot of James standing by a motorcycle with his image reflected in a mirror inside a doorway while Elle's is reflected in the motorcycle's distorting wide-angle mirror. In short, Certified Copy is a dazzling tease of a film that gets inside your head. Whether it's more than that probably depends on how willing you are to unpack its intricacies.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954)

An almost perfect movie. Rear Window has a solid framework provided by John Michael Hayes's screenplay, which has wit, sex, and suspense in all the right places and proportions. The action takes place in one of the greatest of all movie sets, designed by J. McMillan Johnson and Hal Pereira and filmed by Alfred Hitchcock's 12-time collaborator, Robert Burks. The jazzy score by Franz Waxman provides the right atmosphere, that of Greenwich Village in the 1950s, along with pop songs like "Mona Lisa" and "That's Amore" that come from other apartments and give a slyly ironic counterpoint to what L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart) sees going on in them. It has Stewart doing what he does best: not so much acting as reacting, letting us see on his face what he's thinking and feeling as as he witnesses the goings-on across the courtyard or the advances being made on him by Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelly) in his own apartment. It's also Kelly's sexiest performance, the one that makes us realize why she was Hitchcock's favorite cool blond. They get peerless support from Thelma Ritter as Jefferies's sardonic nurse, Wendell Corey as the skeptical police detective, and Raymond Burr as the hulking Lars Thorwald, not to mention the various performers whose lives we witness across the courtyard. It's a movie that shows what Hitchcock learned from his apprenticeship in the era of silent film: the ability to show rather than tell. In essence, what Jeffries is watching from his rear window is a set of silent movies. That Hitchcock is a master no one today doubts, but it's worth considering his particular achievement in this film: It contains a murder, two near-rapes, one near-suicide, serious threats to the lives of its protagonists, and the killing of a small dog, and yet it still retains its essential lightness of tone.

Monday, February 13, 2017

Master of the House (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1925)

Master of the House, Carl Theodor Dreyer's silent comedy-drama, is an ironic title, one attached to the film for its release in English-speaking countries. The original Danish title translates as Thou Shalt Honor Thy Wife, and the play by Sven Rindom on which it was based was called Tyrannens fald -- The Tyrant's Fall. It's also misleading to call it a comedy-drama, although it has moments of mild humor and a happy ending. The tone is seriocomic, or as the original title -- which is echoed in the film's concluding intertitle -- suggests, it's a moral fable. Viktor Frandsen (Johannes Meyer), the master of the house, is an ill-tempered bully, constantly berating his wife, Ida (Astrid Holm), who does everything she can to placate him. For example, she asks him whether he wants the meat she will serve him for lunch to be cold or warm. He answers, as usual irritably, as if he can't be bothered with such mundane matters, that he wants it cold. And then, later, when it's served, he snaps, "Couldn't you have found time to warm it up?" Life for Ida is constant drudgery, taking care of routine household chores, as well as looking after three children, the oldest of which is the pre-teen Karen (Karin Nellemose), whom Ida tries to spare from any of the harder chores that might roughen her hands. What little help Ida gets comes from Viktor's old nanny, known to the family as Mads (Mathilde Nielsen), who drops in to help Ida with the mending -- and to cast a disapproving eye on Viktor's bullying. Eventually, Mads arranges with Ida's mother (Clara Schønfeld) for Ida to escape from the household and rest. More worn out than she knew, Ida has a breakdown, and during her prolonged absence Mads takes over the household and whips Viktor into shape. The story arc is a familiar one -- we've seen it done on TV sitcoms and in Hollywood family comdies -- but it gains strength from the performances and from Dreyer's masterly control of the story and use of the camera. Although Viktor looks like a sheer monster at first, we gain understanding of him when we learn, well into the film, that he is out of work: His business has failed. His absence from the house during the day goes unexplained, although we see him walking the streets and dropping into a neighborhood bar. Nielsen, who had also played the role of Mads on stage, is a marvelous presence in the film, although Dreyer never questions whether, as a nanny who used to administer whippings to Viktor, she might not bear some responsibility for the way he turned out as a man. Best of all, the film gives us a semi-documentary glimpse of what daily life was like for a lower-middle-class family in 1920s Denmark (and presumably elsewhere that modern home appliances hadn't yet taken up some of the burden of housework). Dreyer's meticulous attention to detail -- he served as his own art director and set decorator -- extended to the construction of a four-walled set (walls could be removed to provide camera angles) with working plumbing and electricity and a functioning stove, and he makes the most of it. Master of the House is not quite the pioneering feminist film some would have it be: Ida is a little too sweetly passive even after Viktor reforms. But it's an important step in the growth of Dreyer's moral aesthetic and of his artistry as a filmmaker.

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Yes, Vertigo is a great movie. No, it's not the greatest movie ever made, and to call it that does the film a disservice, inviting skeptics to investigate and overemphasize its flaws. The central flaw is narrative; Vertigo is at heart a preposterous melodrama, and the film raises questions that probably shouldn't be asked: How, for instance, did Scottie (James Stewart) get down from that gutter he was hanging onto after the cop fell to his death? How did Gavin Elster (Tom Helmore) arrange to be at the top of that tower with his dead wife at the exact time when Madeleine (Kim Novak) and Scottie were climbing it? Why is the coroner (Henry Jones) so needlessly hostile to Scottie at the inquest? And so on, until the screenplay by Alec Coppel and Samuel A. Taylor reveals itself to be a thing of shreds and patches. If it is a great film, it's because it had a great director, and that almost no one will gainsay. Alfred Hitchcock drew a magnificent performance from Novak, an actress everyone else underestimated. (And one that he, initíally, didn't want: He was grooming Vera Miles for the role until she became pregnant.) He helped Stewart to one of the highlight performances of his career. He inspired Bernard Herrmann to compose one of the most powerful and evocative film scores ever written -- one whose expression of erotic longing is surpassed perhaps only by passages in Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde. He worked with cinematographer Robert Burks to transform San Francisco and environs into one of the great movie sets. And he turned what could have been a routine thriller (which is what many critics thought it was at the time of its release) into one of the most analyzed and commented-upon films ever made. It will never be my favorite Hitchcock film: I place it below Notorious (1946), Rear Window (1954), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) in my personal ranking of his greatest films, and I enjoy rewatching The 39 Steps (1935), The Lady Vanishes (1938), Foreign Correspondent (1940), and Strangers on a Train (1951) more than I do Vertigo. Yet I still yield to its portrayal of passionate obsession and its masterly blend of all the elements of cinema technology into a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk in which the whole transcends the sometimes indifferent parts.

Saturday, February 11, 2017

Almayer's Folly (Chantal Akerman, 2011)

|

| Stanislas Merhar in Almayer's Folly |

Capt. Lingard: Marc Barbé

Nina: Aurora Marion

Daïn: Zac Andrianasolo

Zahira: Sakhna Oum

Chen: Solida Chan

Director: Chantal Akerman

Screenplay: Chantal Akerman, Henry Bean, Nicole Brenez

Based on a novel by Joseph Conrad

Cinematography: Rémon Fromont

Production design: Patrick Dechesne

Film editing: Claire Atherton

Lots of movies -- think of Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950) and Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2014), for example -- begin with an incident and then flash back for the rest of the movie to explain it. So Chantal Akerman's Almayer's Folly begins with the camera following a Malaysian man into a nightclub where another man is lip-synching to Dean Martin's version of the song "Sway" as a group of women dances behind him. Suddenly the man who entered the club is on stage stabbing the lip-syncher. The music breaks off and all of the dancers flee the stage except one, who continues to perform the hula-like hand movements as if nothing had happened. We hear a voice call out, "Nina! Nina!" but she continues in her trance-like state for a while until she stops and begins to sing Mozart's setting of "Ave Verum Corpus" as the camera holds on her in closeup. The movie then flashes back to reveal that Nina is the daughter of the European Almayer and a Malaysian woman, Zahira. Almayer has come to Malaysia in search of his fortune -- he has heard of a gold mine ripe for the taking. Zahira and Nina live with him in a house by the river until one day his fellow European fortune-hunter, Captain Lingard, arrives to take Nina to the city to be educated: Almayer wants her to have the benefits and privileges of a European lady. Though Zahira and Nina flee into the jungle, Almayer and Lingard capture the girl. Nina is intensely unhappy at the school, scorned by the European girls, and when Lingard, who has been paying her tuition for Almayer, dies, she is expelled. She wanders the streets of the unnamed Malaysian city (the movie was actually filmed in Cambodia) and finally returns to Almayer's home. There she's seduced by Daïn, a shady young man who is supposedly helping Almayer find his fortune. Almayer recognizes his defeat and allows Nina and Dain to leave together. Unlike Wilder and the Coens, Akerman doesn't return to the opening scene at the film's end, but instead leaves us with two of her characteristic long takes: The first shows Almayer, Nina, and Daïn arriving at a sandbar where the river meets the sea to await the arrival of the boat that will take the two young people away; the camera lingers in a long shot as the boat arrives and Nina and Daïn swim out to it, then Almayer and his servant, Chen, push off into the river for their return home. The second long take is a closeup of the haggard, obviously very ill Almayer as he sits brooding in his decaying home, with Chen standing out of focus in the background. At the beginning of this take, Almayer says, "Tomorrow, I would have forgotten," a sentence that he repeats at the end after we watch the sun play across his face -- moving much more swiftly than it would in actuality -- and he talks about how the sun is cold and the river is black. By now, we have realized that the lip-syncher was Daïn and that Chen was his assassin. As for Almayer, we can only assume that he has died. Almayer's Folly, which Akerman loosely adapted from the early Joseph Conrad novel, is clearly a fable about the tragedy of colonialism, but she's not intent on laboring that topic. It's as much an attempt to prod the viewer into contemplating the mystery of character and identity as her more celebrated Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975) was, and by using less radical variations on the same techniques -- extended takes, minimized action -- she used in that film. Akerman developed a compelling and identifiable style, but there is a point at which style becomes mannerism. (We all want to be thought "stylish," and none of us want to be thought "mannered.") I think Almayer's Folly nears that point but doesn't fully reach it, largely because of the compelling performance of Merhar as Almayer, and because of Akerman's use of the setting, with the help of Rémon Fromont's cinematography and Claire Atheron's editing. She also makes fine ironic use of the Dean Martin song and the Mozart hymn, as well as the only non-diegetic music in the film, interludes filled with the erotic longing of Wagner's Prelude to Tristan and Isolde.

Friday, February 10, 2017

The Love Parade (Ernst Lubitsch, 1929)

|

| Jeanette MacDonald and Maurice Chevalier in The Love Parade |

Queen Louise: Jeanette MacDonald

Jacques: Lupino Lane

Lulu: Lillian Roth

War Minister: Eugene Pallette

Ambassador: E.H. Calvert

Master of Ceremonies: Edgar Norton

Prime Minister: Lionel Belmore

Director: Ernst Lubitsch

Screenplay: Ernest Vajda, Guy Bolton

Based on a play by Leon Xanrof and Jules Chancel

Cinematography: Victor Milner

Art direction: Hans Dreier

Film editing: Merrill G. White

Costume design: Travis Banton

Music: Victor Schertzinger

It irritates me a little to think that MGM, thanks largely to those That's Entertainment clip shows in the 1970s, is celebrated for its movie musicals, when in fact the genre was pioneered and perfected at other studios: Warner Bros. with its Busby Berkeley dance spectacles, RKO with its Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers cycle, and Paramount, where Ernst Lubitsch virtually invented the story musical with The Love Parade and subsequent re-teamings of Maurice Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald. (Oddly, today MacDonald is better known for her inferior and unsexy MGM teaming with Nelson Eddy.) MGM didn't achieve musical greatness until the end of the 1930s, when after the success of The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), the studio put its associate producer, Arthur Freed, in charge of the film musicals unit. True, MGM had won a best-picture Oscar with The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont, 1929), but that was a standard backstage musical, not one in which the songs and dances are fully integrated into the plot. Besides, it's almost unwatchable today, whereas thanks to the charm of Chevalier and the sexiness of MacDonald in her revealing pre-Code frippery, but most of all to what is known as "the Lubitsch touch," The Love Parade is still enjoyable. Lubitsch's "touch" as a director was based on a sly conviction that the audience would get the joke, usually a naughty one, and it was perfected during the silent era, when things had to be shown, not told. So the film opens with a mostly silent demonstration of why Count Alfred Renard has caused such a scandal with his dalliances in Paris that he has to be recalled to Sylvania and rebuked by Queen Louise. But this is also a film that wittily integrates sound into its sight gags, as the entire Sylvanian court eavesdrops on the burgeoning love of Alfred and Louise. The plot, derived by screenwriters Guy Bolton and Ernest Vajda from a French play, is standard, slightly sexist stuff about the prince consort, Alfred, feeling miffed by the fact that his marriage to the queen leaves him with nothing to do, but it's carried off well by the leads, as well as the saucy servants, Jacques and Lulu, and a court full of skilled character actors like Eugene Pallette, Edgar Norton, and Lionel Belmore. It's too bad that the song score by lyricist Clifford Grey and composer Victor Schertzinger isn't better -- there are too many reprises of "Dream Lover," for example -- but Lubitsch's staging compensates for its weakness.

Thursday, February 9, 2017

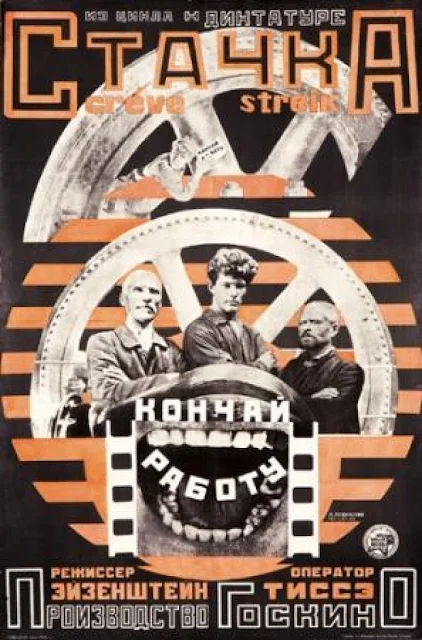

Strike (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

Subtle as a sledgehammer, Sergei Eisenstein's first feature film, Strike, demonstrates the dangerous ability of motion pictures to annihilate thought. With a torrent of images, almost as formidable as the fire hose blasts that mow down the protesting strikers in the fifth "chapter" of the film, the 27-year-old Eisenstein demonstrates a mastery of technique: fast-paced editing, frame-crowding action, provocative close-ups, and powerful montage. The film concludes with a bloodbath -- the "liquidation" of the strikers in their homes, intercut with scenes of cattle being slaughtered in an abattoir -- that makes the Odessa Steps massacre sequence in Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein, 1925) look like a Sunday picnic. The film veers from documentary realism in the factory scenes, to gross -- or perhaps Grosz, as in George Grosz -- caricature in its portrayal of the capitalist bosses as fat cigar-smoking men in silk top hats, to a baroque expressionism in the scenes involving the spies and provocateurs who betray the workers. Eisenstein never slackens for a moment -- it's an exhausting film. Is it a great film? That's one for the debaters, a conflict between those who believe in art as a servant of truth and those who believe in art as pure form. I can admire its technical virtues and historical significance, and even admit that it plays on my political sympathies for workers over capitalist bosses, while worrying that the effect of the film is to valorize a dangerous suppression of reason, the unhinged anti-humanism that ultimately betrayed the very revolution Eisenstein supported.

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

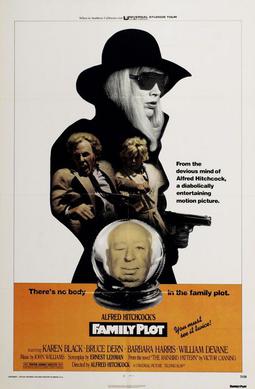

Family Plot (Alfred Hitchcock, 1976)

Barbara Harris, as the "spiritualist" Blanche Tyler, is the best thing about Alfred Hitchcock's last movie. According to Stephen Whitty's The Alfred Hitchcock Encyclopedia, Hitchcock wanted Harris for the role, but he met resistance from the studio, which wanted a bigger name, so he cast Karen Black in the slightly lesser role of Fran to please the higher-ups, who gave Black higher billing than Harris. Which brings up an old question: Why did Harris never become a major star? She made an impressive movie debut in A Thousand Clowns (Fred Coe, 1965), was a standout in Robert Altman's Nashville (1975), and received an Oscar nomination for Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me? (Ulu Grosbard, 1971), but is pretty much forgotten today. She may just be a case of the right talent having been born at the wrong time: Harris had just turned 40 when she made Family Plot. If she had been born a decade later, she might have given Goldie Hawn or, even later, Meg Ryan competition for the romantic comedy roles they became famous for. Family Plot is feather-light lesser Hitchcock, though on the whole it's a return to form for the director after the rather grim Frenzy (1972) and the late misfires Topaz (1969) and Torn Curtain (1967). There are some touches of the master director to be seen in it. The film makes us think that its main story is that of Blanche and her boyfriend George Lumley (Bruce Dern) as they try to track down the missing heir to a fortune, but as Blanche and George are riding in his cab arguing, he suddenly slams on the brakes to avoid hitting a woman crossing the street. The camera takes a sharp left turn and follows the woman instead, taking us into a plot about jewel thieves. The setup is in Ernest Lehman's screenplay, but Hitchcock is classically artful in the way he keeps both plots dangling until we can see how they intersect. There's another glimpse of the master at work in the way he films George trying to meet up with a woman he's trying to question. The scene takes place in a cemetery, and Hitchcock films it with an overhead camera so that we can see the crossing paths among the graves as George maneuvers his way toward the woman. I doubt that Hitchcock ever played one, but the sequence reminds me of a video game maze. Harris, Black, and Dern are all good in their roles, and William Devane is a fine villain. (Though have there ever been toothier leading men than Dern and Devane?) John Williams adds a touch of Bernard Herrmann in some parts of his score, the only one he did for Hitchcock.

Tuesday, February 7, 2017

The Kid With a Bike (Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne, 2011)

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne have said that they were influenced by fairytales when they wrote and directed The Kid With a Bike. Like the Grimm brothers, the Dardenne brothers don't bother giving the backstories of the "good" and "bad" characters in the film. We don't ask how the wicked stepmothers in fairytales got to be so wicked or why the fairy godmothers are so good. In a similar fashion, we are never told what causes Guy Catoul (Jérémie Renier) to be so coldly abrupt in cutting his own son, Cyril (Thomas Doret), out of his life, to the point that he sells the boy's beloved bicycle and puts him into a group home. He provides an economic motive -- he can't afford to support the boy -- but refuses even to make contact with him. Nor do we learn what makes Samantha (Cécile de France) so willing not only to buy the boy's bike from the man Catoul sold it to but also to take the boy himself into her own life. After all, her first encounter with the enraged, belligerent child is in the waiting room of a clinic, where he clings to her for help as the attendants from the group home try to subdue him. She seems to have a settled life as a beautician with a handsome boyfriend. Why borrow such obvious trouble? I felt another literary influence at work in the film: Charles Dickens, who set his tales of rescued orphans like Oliver Twist and David Copperfield in the realistic context of 19th-century England. The Dardennes set their story about Cyril in the context of 21st-century Belgium's working-class suburbs. Like Oliver Twist, Cyril Catoul falls prey to the underworld: He is persuaded to take part in a robbery by a kind of Fagin, a gang leader who calls himself Wesker (Egon Di Mateo), after a character in the Resident Evil video game franchise. The Dardennes don't take a fully neorealist approach to the story the way they do in the only other film of theirs I've seen, Two Days, One Night (2014), which is a movie full of sympathy for those abused by capitalism. The Kid With the Bike is not an exposé, but rather a tribute to human kindness overcoming contemporary anomie. It is made plausible by the matter-of-fact approach of the Dardennes, but mostly by the performances, especially that of 13-year-old Doret, who had never acted before, but brings full conviction to every scene, including his rages and his hunger to be reunited with his father, as well as his eventual acceptance of Samantha's love and authority. The directors never milk a moment for sentiment: The only non-diegetic music on the soundtrack is the occasional punctuation at the end of a scene with a few bars from Beethoven's "Emperor" concerto, which has the tantalizing effect of keeping us suspended until the rest of the adagio is performed over the end credits.

Monday, February 6, 2017

Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

The phrase "fog of war" was coined by Carl von Clausewitz in reference to the cloud of uncertainty that surrounds combatants on the battlefield, but it seems appropriate to apply it to the miscommunication experienced by the soldiers and civilians in Roberto Rossellini's great docudrama about the Allied campaign to liberate Italy in 1943 and 1944. The six episodes in Rossellini's film illustrate various kinds of problems brought about by language, ignorance, naïveté, and lack of necessary information. A young Sicilian woman (Carmela Sazio) struggles to communicate with the G.I. (Robert van Loon) left guarding her; a black American soldier (Dots Johnson) tries to recover the shoes that were stolen from him by a Neapolitan street urchin (Alfonsino Pasco) after he got drunk and passed out; a Roman prostitute (Maria Michi) picks up a drunk American (Gar Moore), but when he tells her of the beautiful, innocent woman he met six months earlier in Rome she realizes that she was the woman; an American nurse (Harriet Medin) accompanies a partisan into the German-occupied section of Florence in search of an old lover; three American chaplains visit a monastery in a recently freed section of Northern Italy, but only the Catholic chaplain (William Tubbs), who speaks Italian, realizes that the monks are deeply shocked that his two companions are a Protestant and a Jew. Only the final -- and the best, most harrowing -- section deals with the traditional concept of the fog of war, as Allied soldiers try to aid Italian partisans in their fight with the retreating but still fierce Germans. As in many Italian neorealist films, the actors are either non-professionals or unknowns, and their uneasiness with scripted dialogue sometimes shows -- at least it does with the English speakers; I can't judge the ones who speak Italian or German. There is also occasional sentimental overuse of the score by the director's brother, Renzo Rossellini. But on the whole, Paisan is still an extraordinarily compelling film, an essential portrait of war and its effects, made more essential by having been filmed on location amid the ruin and rubble so soon after the war ended. Glimpses of the emptied streets of Florence, bare of tourists and trade, are startling, as are the scenes that take place in the marshlands of the Po delta in the final sequence. The cinematography is by Otello Martelli. The screenplay earned Oscar nominations for Alfred Hayes, Federico Fellini, Sergio Amidei, Marcello Paglieri, and Roberto Rossellini, but lost to Robert Pirosh for the more conventional war movie Battleground (William A. Wellman, 1949).

Sunday, February 5, 2017

The Outlaw and His Wife (Victor Sjöström, 1918)

The Outlaw and His Wife is a standard domestic melodrama made memorable by fine performances under the restrained direction of Victor Sjöström, who doesn't allow the usual stagy gesticulations that contemporary viewers often find ludicrous in silent films. Sjöström himself gives a fine performance in the role of the outlaw, Ejvind, who in the middle of a severe famine stole a sheep to feed his family and had to flee after breaking out of jail. He appears one day in a small Icelandic village under the assumed name Kári, and soon wins the heart of Halla (Edith Erastoff), a widow who runs a prosperous farm. Halla's brother-in-law, Björn (Nils Aréhn), also has designs on Halla, and when he discovers that Kári is a wanted man, Ejvind is forced to become a fugitive. Halla gives up everything to join him, and when we see them again they are living happily in the mountains with their small daughter. They are joined by Arnes (John Ekman), who is also on the run, but when Arnes begins to lust after Halla, trouble brews, compounded by the fact that Björn has never relinquished his pursuit of the couple. The film's story, based on a play by Jóhan Sigurjónsson, gains depth from the wild natural setting -- northern Sweden posing as Iceland -- in which the strong simple emotions of the tale seem integral. Sjöström makes the most of the mountain scenery, the waterfalls and hot springs, which are well-photographed by Julius Jaenzon. Sjöström did his own stunt work in a particularly hazardous scene in which Ejvind dangles on a rope from a cliff.

Saturday, February 4, 2017

Onibaba (Kaneto Shindo, 1964)

A dark shocker, with a close kinship to its contemporary, Woman in the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964), Onibaba -- which translates as "Demon Hag," and has been released under the titles Devil Woman and The Hole -- takes place in the grasslands alongside a river during a devastating civil war in medieval Japan. A woman (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura) share a hut there. The older woman's son, who was married to the younger woman, has been conscripted into the army. The two women survive by waylaying samurai who have strayed into the tall grasses, killing them, stripping them, and tossing their bodies into a deep sinkhole. They then exchange the armor and weapons for food and supplies. One day, Hachi (Kei Sato), a neighbor who was conscripted into the army along with the older woman's son, returns and tells them that they had both deserted but the son/husband was killed when he tried to steal food from some farmers. Hachi begins to make a play for the young widow, who is soon sneaking out at night to have sex with him, to the older woman's dismay and jealousy. One night, while spying on Hachi and her daughter-in-law, she encounters a lost samurai general (Jukichi Uno) wearing the mask of a demon. When she asks why he is masked, he says that it's to protect his face: He is, he says, extraordinarily handsome, and if she shows him the way out of the grasslands he will reward her by removing the mask. The woman, however, lures the general to the hole and he falls to his death. She climbs down into the hole, which is filled with skeletons, to retrieve his armor and weapons and to remove the mask, which comes off only after great effort, revealing that he is terribly disfigured. She decides to use the mask to frighten the younger woman off from her liaison with Hachi, but with suitably horrifying consequences. Writer-director Kaneto Shindo plays with the fear of female empowerment and sexuality: The hole, like the sandpit in Woman in the Dunes, is a pretty obvious symbol. But Onibaba makes its way around such heavy-handedness with ferociously committed performances and cinematographer Kyomi Kuroda's striking use of its setting. It has an unusual but effective score by Hikaru Hayashi that blends such disparate elements as taiko drums and jazz saxophones.

Friday, February 3, 2017

Yi Yi (Edward Yang, 2000)

In his Criterion Collection essay on Yi Yi, Kent Jones does something that I endorse completely: He compares writer-director Edward Yang's film to the work of George Eliot. As I was watching Yi Yi, I kept thinking that it gave me the same satisfaction that a good novel does: that of participating in the lives of people I would never know otherwise. George Eliot's aesthetic was based on the premise that art serves to enlarge human sympathy. It's an idea echoed in the film by a character who quotes his grandfather saying that since the introduction of motion pictures, we now live three times longer than we did before -- we experience that many more things The remark in context is ironic, given that the character, a teenager (Pang Chang Yu) who will later commit a murder, mentions killing as one of the experiences now vicariously afforded to us by movies. But the general import of the observation stands: Yi Yi gives us the sweep of life, beginning with a wedding and ending with a funeral, and taking in along the way birth, found and lost love, and other experiences of the Jian family and acquaintances in Taiwan. The central character, N.J. (Nien-Jien Wu), is a businessman caught up in the machinations of his company while trying to deal with family problems: His mother-in-law suffers a stroke and lies comatose; his brother-in-law's wedding to a pregnant bride is interrupted by a furious ex-girlfriend; his wife has an emotional breakdown and leaves for a Buddhist retreat in the mountains; his daughter, Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), is in the throes of adolescent self-consciousness and blames herself because her grandmother suffered a stroke while taking out the garbage Ting-Ting had been told to take care of; his small son, Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang), refuses to join the family in taking turns talking to his comatose grandmother, and he keeps getting in trouble at school. And these matters are complicated by the reappearance of N.J.'s old girlfriend, Sherry (Sun-Yun Ko), now married to a Chicago businessman, who joins N.J. in Tokyo on a business trip that puts him at odds with his company. The separate experiences of N.J., Ting-Ting, and Yang-Yang overlap and sometimes ironically counterpoint one another, and the film is laced together by recurring images and themes. Although it's three hours long, Yi Yi never seems slack. A lesser director would have cut some of the sequences not essential to the narrative, such as the performances of Beethoven's "Moonlight" Sonata and the Cello Sonata No. 1, or the long pan across the lighted office windows in nighttime Taipei, but these give an essential emotional lift to a film that has rightly been called a masterwork.

Links:

Edward Yang,

Jonathan Chang,

Kelly Lee,

Nien-Jien Wu,

Pang Chang Yu,

Sun-Yun Ko,

Yi Yi

Thursday, February 2, 2017

The King of Kings (Cecil B. DeMille, 1927)

Director Cecil B. DeMille always had a fondness for unintentionally hilarious dialogue. Think of Anne Baxter's Nefretiri purring to Charlton Heston's Moses in The Ten Commandments (1956), "Oh, Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid adorable fool!" I'm almost sorry that The King of Kings is a silent film, so that we can't hear Mary Magdalene (Jacqueline Logan) utter the line: "Harness my zebras -- gift of the Nubian king! This Carpenter shall learn that he cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!" After the intertitle card fades, she swans off to rescue her lover, Judas Iscariot (Joseph Schildkraut), from the clutches of Jesus (H.B. Warner). It seems that Judas has become a disciple of Jesus because he believes that he has a chance at a powerful position in the new kingdom that Jesus is planning. This isn't the only hashing-up of the gospels that the credited scenarist, Jeanie Macpherson, commits, but it's the most surprising one. It also gives director DeMille an opportunity to introduce some sexy sinning before he gets pious on us: The Magdalene is vamping around a somewhat stylized orgy and wearing a costume (probably designed by an uncredited Adrian, who was good at that sort of thing) that leaves one breast almost bare. This opening sequence is also in two-strip Technicolor, as is the Resurrection scene some two and a half hours later. Yes, it's an enormously tasteless movie. Warner's Jesus is the usual blue-eyed blond in a white bathrobe found in vulgar iconography, and the actor has little to do but stand around looking wistful and sad at the plight of the world, occasionally giving a little smile that, with Warner's thin, lipsticked mouth, verges dangerously on a smirk. The film goes heavy on the miracles, even recasting one of the gospel writers, Mark, as a boy (Michael D. Moore) cured of lameness by Jesus. (When he throws away his crutch, it accidentally strikes one of the Pharisees standing nearby, only adding to their enmity to Jesus.) Unfortunately, DeMille stages the revival of Lazarus in a way that enhances its creepiness, having him emerge from a sarcophagus swathed in bandages like a horror-film mummy. Still, there's entertainment to be had, if you're not too demanding. Schildkraut's Judas is fun to watch at times: Once, he even skulks away like Dracula with his face hidden by his cloak. His father, Rudolph Schildkraut, plays the sneering high priest Caiaphas, Victor Varconi is a suitably conflicted Pontius Pilate, and William Boyd, soon to make his name as Hopalong Cassidy, is Simon of Cyrene, who helps Jesus carry the cross. The storm and earthquake after the Crucifixion is a DeMille-style special-effects extravaganza. The cinematography by J. Peverell Marley leans heavily on filters and screens to cast halos around Jesus, but does what it can to bring DeMille's characteristic tableau groupings to life. Fortunately, the movie also goes out of its way to avoid arousing antisemitism: The crowds calling for crucifixion are shown to be largely made up of bribed bullies who are suppressing those who want Jesus released, and one man furiously rejects the bribe by saying that as a Jew he cannot betray a brother.

Wednesday, February 1, 2017

An Inn in Tokyo (Yasujiro Ozu, 1935)

|

| Takeshi Sakamoto and Tomio Aoki in An Inn in Tokyo |

Otaka: Yoshiko Okada

Otsune: Choko Iida

Zenko: Tomio Aoki

Kuniko: Kazuko Ojima

Policeman: Chishu Ryu

Masako: Takayuki Suematsu

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Screenplay: Masao Arata, Tadao Ikeda, Yasujiro Ozu

Cinematography: Hideo Shigehara