|

| Machiko Kyo and Ganjiro Nakamura in Floating Weeds |

A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu, 1959)

Monday, May 30, 2016

Open Your Eyes (Alejandro Amenábar, 1997)

I have pretty much forgotten the American remake, Vanilla Sky (Cameron Crowe, 2001), with Tom Cruise. But I'm afraid I'm going to forget the original rather quickly, too. Sci-fi head-spinners generally work for me only if they feature plausible and interesting people. The protagonist of Open Your Eyes, César (Eduardo Noriega), is certainly handsome but otherwise he's just another rich layabout who doesn't seem to have much compunction about stealing Sofia (Penélope Cruz), the young woman his friend Pelayo (Fele Martinez) brings to César's birthday party. But that awakens the jealousy of his ex-girlfriend, Nuria (Najwa Nimri), who offers César a ride in her car and then drives it off a hillside. The accident leaves César disfigured -- and then the plot switches into a complex cross-cutting between reality and nightmare. The premise is intriguing: We learn eventually that the disfigured César, told that plastic surgery can do nothing to restore his good looks, commits suicide so that he can be cryogenically frozen, in the hope that one day be revived and have his face restored. But he also signs a clause that allows for his memories to be replaced with artificial ones, so that he will forget the trauma of the accident and the disfigurement. The unraveling of this plot, devised by Amenábar and Mateo Gil, involves much confusion of identity, including scenes in which César finds Sofia turning into the murderous Nuria. With the aid of the psychologist Antonio (Chete Lara), who may or may not be real, César manages to discover what may or may not have happened -- the film is just that unwilling to make everything explicit. Cruz, who played the same role in the American remake, is quite effective as the lovely Sofia, a victim of César's obsession and Nuria's cruelty, generating the only real suspense in the film.

Sunday, May 29, 2016

Gunga Din (George Stevens, 1939)

Saturday, May 28, 2016

The Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941)

"By gad, sir, you are a character," says Kasper Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), with what Greenstreet's co-star Mary Astor once described as "that evil, hiccupy laugh." He is speaking to Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart), who is certainly a character, if decidedly not a man of character. There aren't many other films so full of characters, but so lacking any with what one might call a moral center. Spade, for one, proves that you can be both misogynistic and homophobic -- as if proof of that were needed. Does he do the right thing at the end when he sends Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Astor) up the river? Perhaps, but he does it with such relish that it's hard to ascribe any probity to the act. The Maltese Falcon is one of the greatest examples of hoodwinking the censors of the Production Code, which among other things forbade depictions of homosexuality on screen. But does anyone miss the fact that Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre) is meant to be gay -- from his fussy little perm to his teasing fondling of the handle of his umbrella to the scent of gardenia that Spade finds so amusing? And probably only the ignorance of Yiddish on the part of the Catholics in the Breen office allows Wilmer (Elisha Cook Jr.) to be called a "gunsel" -- a word that originally meant a young man kept by an older man for sex. Actually, it was Dashiell Hammett who slipped that one by the watchdogs in the original novel -- John Huston kept it, doubtless smiling the sly smile of someone who knows what he's getting away with. Even today, most people probably think like the Breen office and Hammett's editors, that it means a gunman. But Huston also got away with the clear indication that Spade had been having an affair with Iva Archer (Gladys George), the wife of his partner, Miles (Jerome Cowan). And is there anyone who doesn't realize that Spade has slept with Brigid? This was Huston's first feature as a director, and the result of all this Code-dodging, as well as his unwillingness to sentimentalize his characters, made him a formidable directorial force in the years to come, one of the few Hollywood directors who knew how to make movies for adults.

Friday, May 27, 2016

Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

Things I don't like about Citizen Kane:

- The "News on the March" montage. It's an efficient way of cluing the audience in to what it's about to see, but is it necessary? And was it necessary to make it a parody of "The March of Time" newsreel, down to the use of the Timespeak so deftly lampooned by Wolcott Gibbs ("Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind")?

- Susan Alexander Kane. Not only did Welles leave himself open to charges that he was caricaturing William Randolph Hearst's relationship with his mistress, Marion Davies, but he unwittingly damaged Davies's lasting reputation as a skillful comic actress. We still read today that Susan Alexander (whose minor talent Kane exploits cruelly) is to be identified as Welles's portrait of Davies, when in fact Welles admired Davies's work. But beyond that, Susan (Dorothy Comingore) is an underwritten and inconsistent character -- at one point a sweet and trusting object of Kane's affections and later in the film a vituperative, illiterate shrew and still later a drunk. What was it in her that Kane (Orson Welles) initially saw? From the moment she first lunges at the high notes in "Una voce poco fa," it's clear to anyone, unless Kane is supposed to have a tin ear, that she has no future as an opera star. Does she exist in the film primarily to demonstrate Kane's arrogance of power? A related quibble: I find the portrayal of her exasperated Italian music teacher, Matiste (Fortunio Bonanova), a silly, intrusive bit of tired comic relief.

- Rosebud. The most famous of all MacGuffins, the thing on which the plot of Citizen Kane depends. It's not just that the explanation of how it became so widely known as Kane's last word is so feeble -- was the sinister butler, Raymond (Paul Stewart) in the room when Kane died, as he seems to say? -- it's that the sled itself puts so much psychological weight on Kane's lost childhood, which we see only in the scenes of his squabbling parents (Agnes Moorehead and Harry Shannon). The defense insists that the emphasis on Rosebud is mistakenly put there by the eager press, and that the point is that we often try to explain the complexity of a life by seizing on the wrong thing. But that seems to me to burden the film with more message than it conveys.

Thursday, May 26, 2016

L'Avventura (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1960)

The ironic title -- an "adventure" in which nothing adventurous occurs -- is enough to establish L'Avventura as one of the most subversive films ever made. It subverts narrative by never resolving its initial mystery, the disappearance of Anna (Lea Massari). And as a film about sex, it is notably anti-erotic. Antonioni's (and his cinematographer Aldo Scavarda's) camera is in love with Monica Vitti's Claudia, exploring her unconventional beauty in extended closeups. It is the "male gaze" -- the objectifying, depersonalizing view of women -- at its utmost. But then Antonioni subverts the male gaze by two scenes in which it is exposed in full and repellent play: The first is when the would-be celebrity Gloria Perkins (Dorothy De Poliolo) causes a near-riot in the streets of Messina. The second, more bitter scene comes when Claudia, having left Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) to fetch Anna from the hotel in Noto where she thinks she may be staying, begins to be surrounded by more and more men, like a pack of feral dogs, casting eager, exploring stares at her. The sex in L'Avventura is troubled, like that between Anna and Sandro that earlier had left Claudia standing alone and idle in another street. Or the relationship of Claudia and Sandro that develops after Anna's disappearance, leaving neither of them particularly eager to find her. In the end, Sandro proves incapable of remaining faithful to Claudia, all too ready to ease his boredom with, of all people, Gloria Perkins, who returns to prowl the hotel in Taormina in search of paying customers. Before their liaison, Sandro is eyed by a woman who stands in front of a painting of Roman Charity, in which a woman breastfeeds an elderly man, a scene that blurs the distinction between charity and lust. After Claudia discovers Sandro and Gloria in flagrante, she flees the hotel in tears, followed by Sandro, and the film concludes with a scene in which her gestures, stroking his hair as he weeps, demonstrate her own form of charity -- or is it lust? L'Avventura presents us with a world in which the conventional and expected word and action never takes place. It was fashionable at the time the film was released to say that it was a depiction of alienation and ennui. But films about alienation and ennui invariably wind up alienating and boring, as many of the subsequent films made under its influence (including some of Antonioni's own) tediously demonstrated. L'Avventura didn't point out a viable direction for other movies, but it remains, like many great films, sui generis.

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

All About Eve (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950)

|

| Bette Davis and Thelma Ritter in All About Eve |

Eve Harrington: Anne Baxter

Addison DeWitt: George Sanders

Karen Richards: Celeste Holm

Bill Sampson: Gary Merrill

Lloyd Richards: Hugh Marlowe

Miss Casswell: Marilyn Monroe

Birdie: Thelma Ritter

Director: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Screenplay: Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Based on a story by Mary Orr

Cinematography: Milton R. Krasner

Talk, talk, talk. Ever since the movies learned to do it, it has been the glory -- and sometimes the bane -- of the medium. We cherish some films because they do it so well: the films of Preston Sturges, Howard Hawks, and Quentin Tarantino, for example, would be nothing without their characters' abundantly gifted gab. Hardly a year goes by without someone compiling a list of the "greatest movie quotes of all time." And invariably the lists include such lines as "Fasten your seat belts, it's going to be a bumpy night" or "You have a point. An idiotic one, but a point." Those are spoken by, respectively, Margo Channing and Addison DeWitt in All About Eve, one of the movies' choicest collections of talk. Joseph L. Mankiewicz won the best screenplay Oscar for the second consecutive year -- he first won the previous year for A Letter to Three Wives, which, like All About Eve, he also directed -- and in both cases he received the directing Oscar as well. Would we admire Mankiewicz's lines as much if they had not been delivered by Bette Davis and George Sanders, along with such essential performers as Celeste Holm, Thelma Ritter, and, in a small but stellar part, Marilyn Monroe? It could be said that Mankiewicz's dialogue tends to upend All About Eve: The glorious wisecracks and one-liners are what we remember about it, far more than its satiric look at the Broadway theater or its portrait of the ambitious Eve Harrington. We also remember the film as the continental divide in Bette Davis's career, the moment in which she ceased to be a leading lady and became the paradigmatic Older Actress, relegated more and more to character roles and campy films like What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962). All About Eve, in which Margo turns 40 -- Davis was 42 -- and ever so reluctantly hands over the reins to Eve -- Baxter was 27 -- is a kind of capitulation, an unfortunate acceptance that a female actor's career has passed its peak, when in fact all that is needed is writers and directors and producers who are willing to find material that demonstrates the ways in which life goes on for women as much as for men.

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Fury (Fritz Lang, 1936)

The major Hollywood films about lynching -- this one and The Ox-Bow Incident (William A. Wellman, 1943) -- had white men as the victims, when the unfortunate fact is that black men (and a few women) were statistically by far the more frequent targets of vigilante mobs. Not until Intruder in the Dust (Clarence Brown, 1949), can I think of an American film that confronted the reality of the situation. But I don't think Fritz Lang, making his first American film, was thinking about the United States at all when he made Fury. He had seen rampaging mobs in Germany, which is why he left in 1933. That's why the film reaches its full actuality in its scenes of the mob in full cry. Those scenes alone are almost enough to establish the film as a classic, although much of the rest of Fury feels a bit scattered and aimless. It starts like a conventional romantic drama, with Joe Wilson (Spencer Tracy) and Katherine Grant (Sylvia Sidney) window-shopping for furniture for the home they hope to make when they're married. There's some sidetracking into Joe's relationship with his brothers, Charlie (Frank Albertson) and Tom (George Walcott), which although it seems like it will bear fruit -- Charlie has been associating with some shady characters, to which Tom objects -- is pretty much a narrative dead end. And after Katherine leaves for California, where Joe plans to join her when he makes some money, there's an injection of cuteness when Joe adopts a small dog he names Rainbow.* But when Joe finally gets to California his reunion with Katherine is interrupted by the law, who arrest him on the basis of circumstantial evidence as a suspect in a kidnapping. Gossips immediately take up the story and a mob led by a layabout named Kirby Dawson (Bruce Cabot) storms the jail and burns it down with Joe (and Rainbow) inside. Joe escapes (Rainbow doesn't) and goes into hiding, where he plots revenge. Eventually, when a trial leads to conviction of 22 members of the mob and their sentencing to death, Joe is presented with a moral dilemma: to reveal that he's alive, thereby saving the mob members from hanging, or to stay hidden and get his revenge. This being Hollywood, the decision is pretty much a foregone conclusion. Lang's direction is not so sure-handed as it was in his German films, but it keeps Fury watchable even when you spot the holes and compromises in the screenplay he co-wrote with Bartlett Cormack based on a story by Norman Krasna. Tracy is fine, though the character seems to split into two almost discrete roles: the affable Joe of the first half of the film and the obsessive revenge-seeker of the latter part.

*An oddly prescient name: Rainbow is played by Terry, who also played Toto in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939).

*An oddly prescient name: Rainbow is played by Terry, who also played Toto in The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939).

Monday, May 23, 2016

Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942)

|

| Humphrey Bogart, Madeleine Lebeau, and Leonid Kinskey in Casablanca |

Ilsa Lund: Ingrid Bergman

Victor Laszlo: Paul Henreid

Capt. Louis Renault: Claude Rains

Maj. Heinrich Strasser: Conrad Veidt

Signor Ferrari: Sydney Greenstreet

Ugarte: Peter Lorre

Carl: S.Z. Sakall

Yvonne: Madeleine Lebeau

Sam: Dooley Wilson

Emil: Marcel Dalio

Annina Brandel: Joy Page

Berger: John Qualen

Sascha: Leonid Kinskey

Pickpocket: Curt Bois

Director: Michael Curtiz

Screenplay: Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch

Based on a play by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison

Cinematography: Arthur Edeson

Art direction: Carl Jules Weyl

Film editing: Owen Marks

Music: Max Steiner

A few weeks ago, Madeleine Lebeau, the last surviving member of the cast of Casablanca, died at the age of 92. Lebeau played Yvonne, the Frenchwoman with whom Rick Blaine has been having an affair. When he breaks off their relationship coldly, she comes to his cafe on the arm of a German officer to spite him, but when the crowd starts singing the "Marseillaise" to drown out the Germans' singing of "Die Wacht am Rhein," Yvonne, tears streaming down her face, joins in. It's one of the many character vignettes that make Casablanca so entertaining. The film is filled with characters who have nothing at all to do with the main plot: the choice Rick has to make whether to renew his old affair with Ilsa Lund or let her leave Casablanca with her husband, Victor Laszlo. But if the movie simply focused on that love triangle, would it be the classic that it appears today to be? What makes Casablanca such an enduring film, I think, is the texture of its screenplay, which won Oscars for Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, and Howard Koch. And that texture is provided by several dozen character players, to whom somehow the screenwriters managed to give abundant time. The result is such memorable bits as the one in which the waiter, Carl, sits down at a table with an elderly couple, the Leuchtags (Ilka Grüning and Ludwig Stössel), who have just received the visas they need to immigrate to the United States. Carl speaks German to them at first, but the Leuchtags insist that they should speak English so they will fit in when they reach America. Then Herr Leuchtag turns to his wife and asks what time it is:

Liebchen -- sweetness -- what watch?Carl assures them, "You will get along beautiful in America." Has there ever been a movie more quotable? It is, of course, a great movie, largely because everyone took the time to weave such moments into its fabric. I don't claim perfection for it: The subservience of Sam to Rick, whom he calls "Mr. Rick" or "Boss," smacks of the racial attitudes of the era, and I wince when Ilsa refers to Sam as "the boy." (Dooley Wilson was in his 50s when the film was made.) James Agee, who was not as impressed with Casablanca as many of his contemporaries were, "snickered at" some of the expository dialogue, such as Ilsa's plea, "Oh, Victor, please don't go to the underground meeting tonight." But it continues to cast a spell that few other films have ever equaled.

Ten watch.

Such much?

Sunday, May 22, 2016

Cinema Paradiso (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988)

Nostalgia isn't what it used to be. Will today's kids feel sentimental about the multiplexes in which they see movies, the way I feel about the Lyric and the Ritz in the small Mississippi town where I grew up, the places where I learned to love movies? The Ritz, built sometime in the 1930s, was the newer one, and it made a feint at elegance with some art-deco-style trimmings; the Lyric was, I was once told, originally a livery stable. The last I heard, the Ritz was derelict, and the Lyric had been converted into a venue for live music, catering to college students. So since I have my own lost cinema paradises, I should be the right audience for Cinema Paradiso, with its tribute to a bygone era of moviegoing. Tornatore's movie has some good things going on, including the performance of Philippe Noiret as Alfredo, and the wonderful rapport between Noiret and young Salvatore Cascio as Toto. Leopoldo Trieste's performance as the censorious Father Adelfio is also a delight, and ending the film with Alfredo's assemblage of the kissing scenes the priest made him excise is a masterly bit. But once Toto grows up to be the lovestruck teenager Salvatore (Marco Leonardi), I begin to lose interest, as Tornatore's screenplay lards on more and more sentimentality. I've seen it twice now, though I have yet to see the 173-minute "extended cut" of the film, in which, I am told, the grownup Salvatore (Jacques Perrin) is reunited with his teen love Elena (Agnese Nano), now grown up and played by Brigitte Fossey. Frankly, I don't much want to: The 155-minute version seems overlong as it is. Cinema Paradiso is beloved by many, and often makes lists of people's favorite foreign-language films, but I find it thin and conventional.

Saturday, May 21, 2016

Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel Coen and Ethan Coen, 2013)

The flashback is a time-honored storytelling device in movies, but if virtually the entire film is a flashback, it better have a purpose for its existence. In Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), for example, the film flashes back to tell us whose corpse is floating in that swimming pool and why. Inside Llewyn Davis starts with Davis (Oscar Isaac) performing in a Greenwich Village club, then being beaten up for some unknown offense by a man outside that club. The film then flashes back to several days in the life of Davis in which, among other things, he becomes encumbered with a cat, learns that a woman (Carey Mulligan) he knows is pregnant and wants him to fund an abortion, travels to Chicago to try to find a well-paying gig, tries to give up his music career and rejoin the Merchant Marine, and then finally returns to the night he performed at the club and was beaten up, whereupon we learn that he had cruelly heckled his attacker's wife the night before. Is there a meaning to this method of storytelling? If there is, it's probably largely to make the point that Davis is caught in a vicious circle, a spiral of depression and self-destructive behavior. Llewyn Davis is a talented folk musician in a business in which talent alone is not enough: As the Chicago club-owner (F. Murray Abraham) tells him after he performs a song from the album Davis is trying to push, "I don't see a lot of money here." Davis doesn't want a lot of money, just enough to pay for his friend's abortion (which it turns out he doesn't need) and to stop couch-surfing, but every time he is on the verge of making it, something rises up to thwart him. In the movie's funniest scene he goes to a recording gig to make a novelty song, "Please Please Mr. Kennedy," which his friend Jim (Justin Timberlake) has written about an astronaut who doesn't want to go into space -- or as Al Cody (Adam Driver), the other session musician, intones throughout the song, "Outer ... space" -- but he signs away his rights to residuals because he needs ready cash. Of course, the song becomes a huge hit. As unpleasant as Davis can often be, his heart is really in the right place: Not only does he agree to fund his friend's abortion, even though the baby may not be his, he conscientiously looks after the cat he accidentally lets out of the apartment where he has been sleeping, and when the cat escapes again he nabs it on the street -- only, of course, to find out that the cat he has picked up is the wrong one. Are the Coens telling us something about good deeds always being punished? Are they telling us anything that can be reduced to a formula? I think not. What they are telling us is that life can be like that: random, unjust, bittersweet. And that, I think, is enough, especially when the lesson is being taught by actors of the caliber of Isaac (in a star-making role), John Goodman (brilliant as usual, this time as a foul-mouthed junkie jazz musician), and a superbly chosen supporting cast. The Coens always take us somewhere we didn't know we wanted to go, but are glad they decided to take us along.

Friday, May 20, 2016

Close-up (Abbas Kiarostami, 1990)

Like most movie-obsessed kids, I used to imagine myself as the star of my own movie, which happened to be my life. I never imagined myself as the director, but perhaps that's because I didn't know what a director did. Close-up struck a nerve with me, nevertheless, with its eloquent presentation of the entanglement of life and art: It's a documentary about the trial of an unemployed Iranian man whose daydreams about making movies led him to pose as the celebrated director Mohsen Makhmalbaf and to persuade a wealthy family that he was going to use their house as a set and star them in a film. But the remarkable thing about Close-up is that its director, Abbas Kiarostami, then persuaded the Ahankhah family, as well as Hossain Sabzian, the con man, to re-enact the events leading up to the trial. Sabzian and the Ahankhahs -- as well as the journalist Hassan Farazmand; Haj Ali Reza Ahmadi, the judge in the trial; and even Makhmalbaf himself -- appear in the dramatized scenes, proving more than capable actors in playing themselves and creating a simulacrum of the real thing. Kiarostami's film is full of head-spinning tricks of this sort, including a taxi driver who says that he doesn't go to the movies because he's too busy with real life. In the end, when Sabzian is released from prison, he meets with the actual Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Kiarostami was so touched by the encounter of the two men that after shooting the sequence he decided to fake "microphone problems" so as not to intrude upon their privacy. I don't know of any film that more profoundly demonstrates the way movies, the first art form created for and by the masses, have intertwined themselves with our lives. That it should have come from Iran, a country so mysterious to Americans, who pride themselves on having created the motion picture industry, is deeply ironic.

Thursday, May 19, 2016

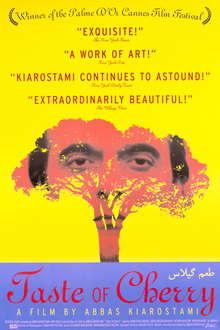

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami, 1997)

I had never seen a film by Kiarostami before, though I knew he was a celebrated Iranian director, so I watched Taste of Cherry with a mostly unbiased eye. I say "mostly" because in his introduction on TCM Ben Mankiewicz commented that although the film won the Palme d'Or at Cannes and has a host of admirers, Roger Ebert found it "excruciatingly boring" and listed it as one of his "most hated films" on his web site. Having seen the film and read the review, I have to wonder if Ebert was in the wrong mood when he saw and wrote about it. I saw it in relaxed anticipation and found it anything but boring. Not a masterpiece, perhaps, but a strangely haunting film, whose images stayed with me through the following day: the winding dirt roads in the hills outside Tehran; the cascades of bare soil turned up by massive agricultural equipment; the shadow of the protagonist, Mr. Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), projected upon these mounds of dirt; the faces of the men the protagonist tries to enlist in his plan: a young soldier (Safar Ali Moradi), a seminarian (Mir Hossein Noori), the taxidermist (Abdolrahman Bagheri). I was struck by the way Kiarostami chose to make those three men aliens in Iran -- a Kurd, an Afghani, a Turk -- as if to emphasize the inner turmoil that mirrors the external conflicts of the region. I was tantalized by the suspense about what Badii wants the other man to do, and as Ebert points out, the fact that we suspect that he is cruising the outskirts of Tehran to find a sexual partner. (Which, given that homosexuality is a capital offense in Iran, is a frighteningly risky thing to do.) And when we learn that Badii wants someone to throw dirt over him after he commits suicide in a grave he has dug for himself, I was intrigued by what has driven him to this brink. But I'm astonished that Ebert took such a literal-minded approach to all of this, wanting to know why we are being led to believe that Badii is gay and to know more about what has driven him to this extremity. Have we not learned long ago not to expect full backstories of characters in literature and film, or to be able to explicate them in some definitive sense? Isn't that why Kiarostami uses the "distancing" device at the end of showing the film itself being made? I'm content with what it tells us of Badii, and with the emotions and ideas demonstrated by the men he picks up: the young soldier's terror, the seminarian's steadfast faith, the taxidermist's hard-earned wisdom. I was struck by the way we watch Badii at the end through the window of his apartment, as if we will never get any closer, but then see his face as he lies in the hole fleetingly illuminated by lightning. But Taste of Cherry is not so much a character-driven film as a fable: a story about the mysteries of human existence and the interplay of lives. It is full of reverberations, not only of one scene with another but of the events in the film with the troubles -- political, social, environmental -- that haunt our times. It can't be reduced to conventional narrative or even allegorical terms. It took me someplace alien -- i.e., Iran, and the possible last day of a man's life -- and yet deeply, humanly familiar.

Wednesday, May 18, 2016

Kameradschaft (G.W. Pabst, 1931)

|

| A Swedish poster for Kameradschaft |

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

The Threepenny Opera (G.W. Pabst, 1931)

In 1928, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill transformed John Gay's 18th-century Beggar's Opera into Die Dreigroschenoper, one of the most celebrated works to come out of Weimar-era Germany, so when sound came to film it was inevitable that the musical should become a movie. But both Brecht and Weill were unhappy with what Pabst decided to do with both the plot and the songs, so they sued. Brecht lost, but Weill won, with the result that although songs were cut from the film, no new music by other composers was added. Brecht's objections seem to be more about a loss of control over the screenplay, which was written by Léo Lania, Ladislaus Vajda, and Béla Balász, than about any ideological shift: If anything, the ending of the film goes even further left than Brecht's did, with the crooks and corrupt officials of the play becoming bankers. Pabst's direction is sometimes a little slow and stiff: He had never done a musical film before, and the action between songs often seems to lag. But the musical numbers that remain -- which include the well-known "Moritat" or "Mack the Knife," Lotte Lenya's delivery of "The Ballad of the Ship With Fifty Cannons," and "The Song of the Heavy Cannon" -- are well-handled. The cast includes Rudolf Forster as Mackie Messer (i.e. Mack the Knife), Carola Neher as Polly Peachum, Fritz Rasp as Peachum, and Lenya as Jenny. It's striking to see that, as in Fritz Lang's M, made the same year, the underworld is presumed to consist of syndicates of thieves and beggars. The cinematography is by Pabst's frequent collaborator, Fritz Arno Wagner, and the splendid sets are by Andrej Andrejew.

Monday, May 16, 2016

Westfront 1918 (G.W. Pabst, 1930)

|

| A Swedish poster for Westfront 1918 |

Sunday, May 15, 2016

Diary of a Lost Girl (G.W. Pabst, 1929)

Diary of a Lost Girl feels like a falling-off from the standard set by Pabst's first film with Louise Brooks, Pandora's Box (1929), in large part because its source, a 1905 novel by Margarete Böhme, was less distinguished than the one for the previous film: Frank Wedekind's two Lulu plays, which inspired not only Pabst's film but also Alban Berg's 1937 opera, Lulu. The print shown on TCM is also less successfully restored than that of Pandora's Box, owing to difficulties with censors that resulted in some major cuts that sometimes leave the narrative a bit hard to follow. Brooks plays Thymian Henning, the daughter of a well-to-do pharmacist (Josef Rovensky). She is raped and impregnated by her father's assistant, Meinert (Fritz Rasp). When she gives birth, her baby is taken away and she is expelled from her father's home, with the connivance of the housekeeper, Meta (Franziska Kinz), who later marries Thymian's father. She escapes from the oppressive reformatory to which she is sent and winds up in a high-class brothel. When her father dies, she expects an inheritance and marries her friend Count Orloff (André Roanne), who has been disinherited by his own father (Arnold Korff). But when he receives the money she discovers that Meta and her two children have been left penniless. Rather than allow her young half-sister to suffer the fate she has experienced, she gives away her fortune to Meta. Learning of this, Count Orloff leaps to his death from an open window, but his father takes Thymian in, allowing her not only to continue to prosper but also to take revenge on the reformatory personnel who had mistreated her. The elder Count Orloff then observes, "A little more love and no one would be lost in this world." That a story so improbable and sententious should work at all is a tribute to Pabst's willingness to take it seriously and to marshal a cast that performs it with apparent conviction. Brooks, however, feels miscast, especially after her triumph in Pandora's Box: It's difficult to accept the broad-shouldered, strong-backed Brooks as a 15-year-old, which she presumably is at the film's beginning when she attends her confirmation, and the performance feels one-note after the impressive range she achieved in the first film. It was not a critical or commercial success, owing in part to the arrival of sound, which made it feel obsolete, and it didn't receive an American commercial release.

Saturday, May 14, 2016

Pandora's Box (G.W. Pabst, 1929)

Louise Brooks left a legend far greater than her real achievement as an actress, but even today few people have seen her films. In our own time, the fascination with Brooks seems to have begun in 1979 with a profile by Kenneth Tynan in the New Yorker, which revealed that the actress who made her last movie in 1938 was alive and living in Rochester, N.Y. Such was the power of Tynan's prose that people began to seek out her existing films, primarily this one, to discover what the fuss was about. What we see here is a healthy young woman -- she was 23 when the film was released -- with whom the camera, under Pabst's influence, is fascinated. There is a deep paradox in Brooks and her career: the American girl who found success in the troubled Europe between two wars; the vivid personality who briefly dazzled two continents but faded into obscurity; the liberated woman who had affairs with such prominent men as CBS founder William S. Paley as well as with women including (by her account) Greta Garbo but wound up a solitary recluse. And all of this seems perfectly in keeping with her most celebrated role in this film. For despite her bright vitality, her flashing dark eyes and brilliant smile, Brooks's Lulu becomes the ultimate femme fatale, careering her way toward destruction, not only of her lovers but eventually of herself. The story has it that Pabst was so infatuated with Brooks in her Hollywood films that he insisted on her for the part but Paramount wouldn't release her from her contract, so Pabst tried to cast Marlene Dietrich before Brooks up and quit the Hollywood studio. It's hard to imagine Pandora's Box with Dietrich, as the film is so built around Brooks's liveliness as opposed to Dietrich's sultry languor. The screenplay, by Ladislaus Vajda from two plays by Frank Wedekind, tosses us right into the middle of Lulu's affair with Dr. Ludwig Schön (Fritz Kortner), the executive editor for a newspaper. Eventually, she goes on trial for Schön's murder, but escapes with the help of his son, Alwa (Francis Lederer), and her trio of oddball cronies, the grotesque Schigolch (Carl Goetz), who may be her father or just her pimp (the film leaves many such questions tantalizingly unanswered), the lesbian Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), and the acrobat Rodrigo Quast (Krafft-Raschig). She comes to a bad end in London, where she turns to prostitution and is murdered by Jack the Ripper (Gustav Diessl). The acting is terrific throughout, as is the atmosphere created by Günther Krampf's cinematography. The film has been admirably restored, but with one reservation: a terribly obtrusive score by Gillian Anderson (not the actress) that's meant to reproduce what a high-end European movie house with full orchestra would play to accompany the film. That may be the case, but it's a pastiche of themes from classical music that don't always echo what's being shown on screen. It's the only version I've seen on TCM, though the Criterion Collection DVD contains three alternative scores, which I would like to hear.

Friday, May 13, 2016

Woman in the Dunes (Hiroshi Teshigahara, 1964)

Woman in the Dunes is an absurdist thriller: An entomologist (Eiji Okada, gathering specimens in the sand dunes along the seashore, misses his bus and asks the locals for shelter for the night. He is lodged with a widow (Kyoko Kishida) who lives alone in a shack at the bottom of a pit, but in the morning discovers that he is trapped, unable to climb from the pit, and forced to stay with her and shovel sand that the villagers collect during the day and exchange for provisions. As the days pass, he tries various ways to escape, but in the end, even though he is given the means to leave, he accepts his lot and remains. Introducing the film on TCM, Ben Mankiewicz made much of the fact that since its release, there have been many efforts to determine what the film "means," as if the whole compelling drama were simply a vehicle for some sort of message. But to borrow from Archibald MacLeish's oxymoronic poem "Ars Poetica," a movie, like a poem, "should not mean / But be." Teshigahara's film is what it is: a compelling story overlaid with eroticism that, only because of the strangeness and even improbability of its setting, suggests more than it states. It works largely because of the performances of Okada and Kishida, who give their characters a compelling tension, an oscillation between tenderness and violence. The key scene takes place when, after having settled into the routine of their life together, the man pleads with the villagers to let him leave the pit for an hour each day, just to look at the sea. The villagers agree, but with a terrible condition: Wearing hideous masks, they gather at the edge of the pit to watch the man and the woman copulate. In his desperation, the man pleads with the woman to comply, and when she refuses he attempts to rape her. Teshigahara's direction, Hiroshi Segawa's cinematography, and Toru Takemitsu's music add to the horror of the scene, just as they make the entire film extraordinarily memorable, if not some kind of statement about the human condition. Kobo Abe wrote the screenplay, based on his 1962 novel.

Thursday, May 12, 2016

Jurassic World (Colin Trevorrow, 2015)

It doesn't take long for déjà vu (not to say ennui) to set in when you're watching this movie. If the title alone doesn't incite it, the use of John Williams's theme for Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993) will certainly do it. (The movie's main score is by Michael Giacchino.) So what are we dealing with here: a sequel, a reboot, or a remake? And does it really matter? There is a deep cynicism underlying this movie, made manifest even in the dialogue: Claire (Bryce Dallas Howard), the theme park's operations manager, says, "We've been pre-booking tickets for months. The park needs a new attraction every few years in order to reinvigorate the public's interest. Kind of like the space program. Corporate felt genetic modification would up the wow factor." Not once does Jurassic World question the plausibility of opening a new dinosaur theme park 20 years after the disasters depicted in the original film and its 1997 and 2001 sequels. (Although 32 years have passed between the original and this sequel/reboot/remake, the new film seems to assume that the first one took place in 2003.) All that matters is the wow factor. The trouble is that the 1993 film has a bit more than just wow: It had genuine awe, not only at the film technology but in the imaginative evocation of what it would really be like to encounter living dinosaurs. It had plausible characters, embodied by Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, and Richard Attenborough. In their place, Jurassic World has a hunky motorcycle-riding velociraptor-whisperer (Chris Pratt), a slightly ditzy spouter of corporate-speak in heels (Howard), and a hissable villain who wants to militarize genetically engineered saurians (Vincent D'Onofrio). Fortunately, all three actors are more than capable of making the most of their stock characters, particularly Pratt, who seems to be emerging as the new Harrison Ford. And fortunately, everyone concerned with making the film knows how to hype up the action. Which is necessary, because whenever the film slows for something resembling thought or human behavior -- as when the two young brothers, Zach (Nick Robinson) and Gray (Ty Simpkins), are left alone to reflect on whether their parents are getting divorced -- the film stagnates. At those moments, we can only reflect on how much better the original film was at making you believe in its humans. Why, for example, does this one have two boys as its juvenile protagonists when the original had a boy and a girl? And why has Laura Dern's capable paleobotanist been replaced by Howard's MBA type? Not to mention that the women in the film, Claire and her assistant, Zara (Katie McGrath), who is entrusted with looking after the boys, and the boys' mother, Karen (Judy Greer), are depicted as women whose focus on their careers put others in danger. There is fun to be had in the movie, but only if you're willing to overlook what its subtext tells us about how things have changed, and not for the better, in 30 years.

Wednesday, May 11, 2016

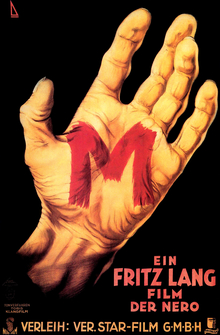

M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

Point of view is everything in a thriller. Let the viewer see events through the wrong eyes, and suspense goes out the window. The remarkable thing about Lang's great thriller is that the point of view changes so often. It starts with that of anxious parents, knowing that a child-killer is on the loose, then narrows to one particular parent, waiting for her daughter to come home from school for lunch. But then we see the object of her fears, her daughter, making contact with a strange man, and our suspense builds as we return to the worried mother. But as strongly as we sympathize with the mother, we also eventually learn to focus our anxieties elsewhere: on the beleaguered police, on innocent victims of people's suspicions, on the criminal underworld harassed by the police, and eventually even on the murderer himself. There are even moments when, as he becomes the object of the manhunt, trapped in the attic of a building swarming with the criminals in search of him, we find ourselves semi-consciously rooting for him to escape. Then we find ourselves rooting for the criminals to capture him and to escape being caught by the cops. And then, when he is put on trial by the criminals, we root for the police to arrive and rescue him. In short, the movie is a study in the ways in which sympathy can be manipulated. Lang and his soon-to-be-ex-wife Thea von Harbou wrote the screenplay, and the atmosphere of the film is superbly maintained by the cinematography of Fritz Arno Wagner and the sets of Emil Hasler and Karl Vollbrecht. But none of it would work without the presence of some extraordinary performers, starting with Peter Lorre as the sniveling, obsessed Hans Beckert: a career-defining performance in many ways, considering that Lorre had been known for comic roles on stage before Lang made him a movie star. Then there's Otto Wernicke as Inspector Lohmann, whose performance was so memorable that Lang brought him back as the same character in The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), stereotyping Wernicke as a cop for much of his career. And Gustav Gründgens, the imperious leader of the criminal faction, who later became identified with the role of Mephistopheles in stage and screen versions of Goethe's Faust (Peter Gorski, 1960) -- not to mention in Klaus Mann's 1936 novel, Mephisto, based on Gründgens's embrace of the Nazis to advance his career.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927)

Metropolis strikes me as the most balletic movie ever made. I'm not referring just to Brigitte Helm's fabulous hoochie-coochie as the False Maria, which so thrills the goggling, slavering gentlemen of Metropolis, but to the fact that as one of the great silent films it brilliantly substitutes movement for the speech and song the medium denies it. In addition to Helm's terrific performance as both Marias, we also have Gustav Fröhlich's wildly over-the-top Freder, who flings himself frenziedly about the sets. We may find the performance laughable today, but it's best to watch the film with the understanding that subtlety just wouldn't work in Fritz Lang's fever-dream of a city. Certainly that's also true of the always emotive Rudolf Klein-Rogge, whose Rotwang is pretty much indistinguishable from his Dr. Mabuse. But even the stillest of the characters in the film -- Alfred Abel's Joh Frederson, Fritz Rasp's superbly creepy Thin Man -- are there to provide a sinister contrast to the hyperactivity going on around them. And then there are the crowds, a corps de ballet if ever there was one, whether stiffly marching to and from their jobs, or celebrating the fall of the Heart Machine with a riotous ring-around-the-rosy. There are times when Lang's manipulation of crowds reminds me of Busby Berkeley's. Lang's choreographic approach to the film is essential to its success as a portrayal of the subsuming of the human into the mechanical. Is there a more brilliant depiction of the alienation of work than that of the man who must shift the hands around a gigantic clock face to keep up with randomly illuminated light bulbs? Metropolis is usually cited as a triumph of design, and it probably wouldn't have the hold over us that it does without the sets of Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht, whose influence over our visions of the future seems indelible. Would we have the decor of the Star Wars movies or any of today's superhero epics without their work? There are those who would argue that the film is long on visual excitement but short on intellectual content -- the moral banality, that the Heart must mediate between the Head and the Hand, hardly seems to suffice as a justification for the film's Sturm und Drang -- which weakens its reputation as a masterpiece. But that seems to me to ask more of movies than they were ever designed to provide. So much in Metropolis reverberates with history -- from the French Revolution to the Bolsheviks to the Nazis -- that it's a film we can never get out of our heads, and probably shouldn't.

Monday, May 9, 2016

The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)

Lang's Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922) hardly needed a sequel, but the director makes it worth our while by adding sound to the concoction. Take, for example, the segue from the tick ... tick ... tick of the timer on a bomb to the chip ... chip ... chip of someone removing the shell from a soft-boiled egg. It's a witty touch that not only eases tension with laughter, but also demonstrates the prevalence of the sinister in everyday life. Hitchcock, it is often noted, learned a great deal from Lang. Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is more of a felt presence than a visible one in this version, confined as he is to an insane asylum where he supposedly dies, only to haunt not only the inmate Hofmeister (Karl Meixner) but also, and especially, the head of the asylum, Prof. Baum (Oscar Beregi Sr.), who is compelled to carry out Mabuse's plans for world domination. As in the 1922 film, there is a doughty policeman, Commissioner Lohmann (Otto Wernicke), who is determined to foil Mabuse's nefarious plans. Wernicke, whose character Lang brought over from M ( 1931), is not as hunky as the earlier film's von Wenk (Bernhard Goetze), so Lang and screenwriter Thea von Harbou add to the mix a young leading man, Gustav Diessl, who plays Thomas Kent, an ex-con who escapes from Mabuse's snares to aid Lohmann in trapping Baum in his efforts to fulfill Mabuse's plot. It's extremely effective suspense hokum, not raised quite to the level of art the way the 1922 film was, but still a cut above the genre. As is usually noted, this was Lang's last film in Germany. It was suppressed by the Nazis, ostensibly because it suggested that the state could be overthrown by a group of people working together, but perhaps also because of its suggestion that world domination might not be such a good thing.

Sunday, May 8, 2016

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (Fritz Lang, 1922)

It's a four-and-a-half-hour movie, and I've seen two-hour movies that felt longer. It zips along because Fritz Lang never fails to give us something to look at and anticipate. There is, first and foremost, the hypnotic (almost literally) performance of Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Mabuse, a role that could have degenerated into mere villainous mannerisms. There is his dogged and thwarted but always charismatic opponent, von Wenk (Bernhard Goetzke), who seems on occasion to resist Mabuse's power by mere force of cheekbones. There is the extraordinary art decoration provided by Otto Hunte and Erich Kettelhut, which often gives the film its nightmare power: Consider, for example, the exceedingly odd stage decor provided for the Folies-Bergère performance by Cara Carozza (Aud Egede-Nissen), in which she contends with gigantic heads with phallic noses (or perhaps beaks), or the collection of primitive and Expressionist art belonging to the effete Count Told (Alfred Abel). The story itself, adapted from the novel by Norbert Jacques by Lang's wife-to-be Thea von Harbou, is typically melodramatic stuff about a megalomaniac psychiatrist, who uses his powers to become a master criminal. But l think it succeeds not only because it has so much to say about the period in which it was made -- i.e., "from Caligari to Hitler," as TCM's programmers would have it, following up on a documentary about Weimar Republic-era filmmakers based in part on the 1947 book by Siegfried Kracauer -- but also because of our continuing fascination with mind control. Maybe it's just because this is a presidential election year, but I'm reminded that there's a little Mabuse in everyone who seeks power. Somehow we continually lose our skepticism, born of hard experience, about the manipulators and find ourselves once again yielding to them. And somehow we usually, like von Wenk, find a way to pull ourselves back from the brink. But, as Lang himself experienced, we don't always manage to do so.

Saturday, May 7, 2016

Mr. Arkadin (Orson Welles, 1955)

|

| Michael Redgrave in Mr. Arkadin |

Guy Van Stratten: Robert Arden

Mily: Patricia Medina

Burgomil Trebitsch: Michael Redgrave

Jakob Zouk: Akim Tamiroff

Sophie: Katina Paxinou

The Professor: Mischa Auer

Thaddeus: Peter van Eyck

Raina Arkadin: Paola Mori

Baroness Nagel: Suzanne Flon

Director: Orson Welles

Screenplay: Orson Welles

Cinematography: Jean Bourgoin

Art direction: Orson Welles

Film editing: Renzo Lucidi, William Morton, Orson Welles

Music: Paul Misraki

"What if?" is the question that haunts every Orson Welles film after Citizen Kane (1941). What if Welles had had the financial, production, and distribution support for his films? Of none of them is the question more appropriate than Mr. Arkadin, which was edited by other hands than Welles's and not even shown in the United States until 1962, and at one point was said to exist in at least seven different versions. In 2006, the Criterion Collection released a three-DVD set that edited together all of the existing English-language versions of the film, following what was known of Welles's original plan, along with his comments on some of the other versions that had been released. It's probably as close as we're going to get to what the director had in mind. So what if Mr. Arkadin had been under Welles's control all along? Would we have a more coherent narrative and style? Would the protagonist, Guy Van Stratten, have been played by a more skilled actor than Robert Arden? (It's a role that would have been perfect for someone like William Holden.) Would Welles have called on the best makeup artists to provide him with a more convincing prosthetic nose and a wig and beard whose edges don't show? Would the function and the fate of Patricia Medina's character, Mily, have been clearer? And does any of this really matter? For what we have here, despite Welles's later description of the film (or its handling) as a "disaster," is one of the most fascinating works in his storied, troubled career. There are sequences that are haunting, even if their purpose in the film is unclear, such as the procession of the penitentes, who in their tall, pointed hoods look like exactly what Mily mistakes them for: "crazy ku kluxers." Or the Goyaesque masks at Arkadin's ball. Or the sequence of truly wonderful cameo performances, including a hair-netted Michael Redgrave as the junk dealer Burgomil Trebitsch, who keeps trying to sell Van Stratten a busted telescope (which he pronounces "telly-o-scope"). Or Mischa Auer as the proprietor of a flea circus. Or Katina Paxinou as a Mexican (?) woman named Sophie. And then there's one of Welles's most celebrated speeches, perhaps second only to his "cuckoo clock" monologue in The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949), in which Arkadin tells the fable of the scorpion and the frog. Though analogues have been found in folklore around the world, this particular formulation of it seems to have been Welles's own:

This scorpion wanted to cross a river, so he asked the frog to carry him. No, said the frog, no thank you. If I let you on my back you may sting me and the sting of the scorpion is death. Now, where, asked the scorpion, is the logic in that? For scorpions always try to be logical. If I sting you, you will die. I will drown. So, the frog was convinced and allowed the scorpion on his back. But, just in the middle of the river, he felt a terrible pain and realized that, after all, the scorpion had stung him. Logic! Cried the dying frog as he started under, bearing the scorpion down with him. There is no logic in this! I know, said the scorpion, but I can't help it -- it's my character.Perhaps it was Welles's character that betrayed him into making movies that flopped but turned into classics.

Friday, May 6, 2016

Pépé le Moko (Julien Duvivier, 1937)

When Walter Wanger decided to remake Pépé le Moko in 1938 as Algiers (John Cromwell), he tried to buy up all the existing copies of the French film and destroy them. Fortunately, he didn't succeed, but it's easy to see why he made the effort: As fine an actor as Charles Boyer was, he could never capture the combination of thuggishness and charm that Jean Gabin displays in the role of Pépé, a thief living in the labyrinth of the Casbah in Algiers. It's one of the definitive film performances, an inspiration for, among many others, Humphrey Bogart's Rick in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943). The story, based on a novel by Henri La Barthe, who collaborated with Duvivier on the screenplay, is pure romantic hokum, but done with the kind of commitment on the part of everyone involved that raises hokum to the level of art. Gabin makes us believe that Pépé would give up the security of a life where the flics can't touch him, all out of love for the chic Gaby (Mireille Balin), the mistress of a wealthy man vacationing in Algiers. He is also drawn out of his hiding place in the Casbah by a nostalgia for Paris, which Gaby elicits from him in a memorable scene in which they recall the places they once knew. Gabin and Balin are surrounded by a marvelous supporting cast of thieves and spies and informers, including Line Noro as Pépé's Algerian mistress, Inès, and the invaluable Marcel Dalio as L'Arbi.

Thursday, May 5, 2016

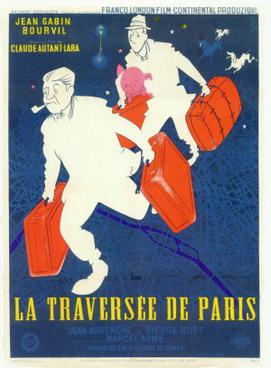

Four Bags Full (Claude Autant-Lara, 1956)

Like most movie-lovers whose knowledge of film extends beyond "Hollywood," I was familiar with Jean Gabin, especially through his work for Jean Renoir in Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and French Cancan (1955). But although I had encountered the name, I didn't know Bourvil, celebrated in France but not so much on this side of the Atlantic. Which made it difficult for me at first to capture the tone and humor of Four Bags Full, a film also known as La Traversée de Paris, The Trip Across Paris, and Pig Across Paris. Since the film begins with newsreel footage of German troops occupying Paris in 1942, it strikes a more serious tone than it eventually takes. Marcel Martin (Bourvil) is a black market smuggler tasked with carrying meat from a pig that's slaughtered at the beginning of the movie while he plays loud music on an accordion to cover its squeals. He's responsible for transporting two suitcases filled with pork across the city to Montmartre, but when the other smuggler fails to show up, he has to accept the aid of a stranger, Grandgil (Gabin), who agrees to carry the other two valises. Grandgil, however, wants the butcher, Jambier (Louis de Funès), to pay much more than the originally agreed-upon amount for his services, and blackmails him into accepting, to the consternation of Martin. The task is perilous, given the vigilance of the French police and the German occupying troops, so the film wavers between thriller and comedy -- the latter particularly when some stray dogs pick up the scent of what's in the suitcases. The film ends up being a fascinating tale of the odd-couple relationship between Grandgil and Martin, as well as a picture of what Parisians went through during the occupation. It was controversial when it was released because it takes a warts-and-all look at black-marketeers and the Résistance, downplaying the heroism without denying the genuine risks they took. Eventually, Grandgil and Martin are caught by the Germans, but Grandgil is released because the officer in charge recognizes him as a famous artist. Martin is sent to prison, but the two are reunited after the war when Grandgil recognizes him at a train station as the porter carrying his luggage -- a rather obvious, and somewhat sour, bit of irony.

Wednesday, May 4, 2016

Wild Rose (Sun Yu, 1932)

|

| Wild Rose director Sun Yu |

|

| Wang Renmei in Wild Rose |

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

The Young Girls of Rochefort (Jacques Demy, 1967)

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac in The Young Girls of Rochefort |

Solange Garnier: Françoise Dorléac

Yvonne Garnier: Danielle Darrieux

Andy Miller: Gene Kelly

Étienne: George Chakiris

Maxence: Jacques Perrin

Simon Dame: Michel Piccoli

Bill: Grover Dale

Josette: Geneviève Thénier

Subtil Dutroux: Henri Crémieux

Director: Jacques Demy

Screenplay: Jacques Demy

Cinematography: Ghislain Cloquet

Production design: Bernard Evein

Film editing: Jean Hamon

Music: Michel Legrand

I appreciate Jacques Demy's hommage to the Hollywood musical, but I think I would have to like Michel Legrand's songs more to really enjoy The Young Girls of Rochefort. Demy's The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) has been known to seriously divide and damage friendships, though when I last saw it I rather enjoyed its cheeky sentimentality and bright colors. Rochefort takes a similar approach to Cherbourg, setting a musical romance in a French town and filling it with wall-to-wall Legrand songs, but by doubling down on the concept -- giving us multiple romances, extending the time from Cherbourg's 91 minutes to Rochefort's more than two hours, and bringing in guest stars from American musicals -- it begins to try one's patience. Catherine Deneuve, who starred in Cherbourg, is joined by her sister, Françoise Dorléac, and the two of them have great charm, though Deneuve's delicately beautiful face is smothered under an enormous blond wig for much of the film. They are courted by Étienne and Bill, who often seem to be doing dance movements borrowed from Jerome Robbins's choreography for West Side Story (Robbins and Robert Wise, 1961), in which the actor playing Étienne, George Chakiris, appeared. (Rochefort's choreographer is Norman Maen.) But Solange winds up with an American composer, Andy Miller, while Delphine keeps missing a connection with Maxence, an artist who has painted a picture of his ideal woman who looks exactly like Delphine. Meanwhile, their mother, Yvonne, doesn't realize that her old flame (and the father of her young son), Simon Dame, has recently moved to Rochefort. (She had turned him down because she didn't want to be known as Madame Dame. No, I'm not kidding.) And so it goes. The movie is given a jolt of life by Gene Kelly's extended cameo: At 55, he's as buoyant as ever, though somewhat implausible as the 25-year-old Dorléac's love interest. He would have been better paired with Darrieux. It's a candy-box movie, but for my taste it's like someone got there first and ate the best pieces, leaving me the ones with coconut centers.

Monday, May 2, 2016

Faust (F.W. Murnau, 1926)

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922)

As Bram Stoker first described him, Count Dracula was by no means hideous. Creepy, yes, but with his long white mustache, his aquiline nose, and his "extraordinary pallor," he must have been at least striking to see. Most of the incarnations of Count Dracula on screen have been more or less attractive men: Bela Lugosi, Christopher Lee, Jack Palance, Frank Langella, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, among many others. And lately, since Anne Rice's novels and Buffy the Vampire Slayer's Angel (David Boreanaz) and Spike (James Marsters), the tendency has been to portray vampires as hot young dudes like the ones seen on the CW's The Vampire Diaries and The Originals. Vampires, it seems, have been getting more human. But not the very first version of Dracula portrayed on screen: With his steady glare, his beaky nose, his batlike ears, his long taloned fingers, his implacable stiff-legged gait, and his posture suggestive of someone who has been crammed for a long time into a coffin, Max Schreck's Count Orlok (the name has been changed to protect the studio, which it didn't) is decidedly non-human. He's a mutant, perhaps, or an alien. He is also not sexy, which is something of a paradox because vampirism, with its night prowling and exchange of fluids, is all about sex -- or the fear of it. And yet this is probably the greatest film version of Dracula, even allowing for the fact that it's a ripoff, designed to allow the producers Enrico Dieckmann and Albin Grau to avoid having to pay the Stoker estate for the rights. They were sued, and according to the terms of the settlement all prints of the film were supposed to be destroyed. The studio went out of business, but Nosferatu was undead -- enough copies survived that it could be pieced together for posterity. Undead, but not undated: Some of the opening scenes involving Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim), the novel's Harker, are a bit laughable given the actor's puppyish grin, and the character of Knock (Alexander Granach), the novel's Renfield, is wildly over-the-top. But Murnau knew how to create atmosphere, and he keeps the action grounded in plausibility by using real locations and natural settings. The scene in which a long procession of coffins filled with plague victims moves down a street (actually in Lübeck) is haunting. But most of all, it's Schreck's uncanny performance that makes Nosferatu still able to stalk through dreams after more than 90 years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)