A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Thursday, December 31, 2015

Swing Time (George Stevens, 1936)

The plot of a Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers is typically a thread on which the gems (the songs and dances) are strung, and Swing Time is no exception. The screenplay by Howard Lindsay and Allan Scott seems to exist largely to provide opportunities for Astaire and Rogers to open their mouths, the better to sing with, or to find places to dance. For those who care, it's the one in which Astaire plays a gambler named Lucky Garnett, who is late for his wedding to Margaret Watson (Betty Furness), so her father calls it off and says that if Lucky can make $25,000, he can come back to claim her hand. So off he goes to New York, accompanied by his friend Pop Cardetti (Victor Moore), where he falls for Penny Carroll (Rogers), a dance teacher. And so on.... That anything this silly remains watchable 80 years later is the consequence of the unsurpassed artistry of Astaire and Rogers, the dance direction of Hermes Pan, the comic support of Moore, Helen Broderick, and Eric Blore, and six songs by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields. Rogers does more than her usual share of the singing in this one, taking the lead on both "Pick Yourself Up" and "A Fine Romance," but as usual it's Astaire's peerless phrasing that carries the songs, especially the Oscar-winning "The Way You Look Tonight," which is wittily staged when Rogers enters the room having lathered her hair with shampoo but not yet rinsed it out. The dance highlight is probably "Never Gonna Dance," the climactic number when Lucky and Penny each think they're doomed to marry someone else, but Astaire's solo, "Bojangles of Harlem," a tribute to the great Bill Robinson, is also superb -- as long as you're not offended by the fact that Astaire does it in blackface. (To my mind, the reverence paid to Robinson outweighs the minstrelsy, but only slightly.) Astaire always insisted that dance sequences be done in long takes, which led to 47 reprises of "Never Gonna Dance" during the filming before a take that completely satisfied Astaire was achieved -- at the expense, it is said, of Rogers's feet, which began to bleed. This was the only film role of any consequence for Furness, whose chief claim to fame was that she opened countless refrigerator doors as the TV commercial spokesperson for Westinghouse in the 1950s.

Wednesday, December 30, 2015

Summer With Monika (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

This early Bergman film, coming before the trifecta of Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), The Seventh Seal (1957), and Wild Strawberries (1957) established his reputation as a director, got its first exposure in the United States in 1955 when an enterprising distributor purchased the rights, cut it by a third, and released it as Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl, with a publicity campaign centered on Harriet Andersson's nude scene. As the original poster at left suggests, the Swedish distributors were not above exploiting Andersson either, but Bergman's adaptation with Per Anders Fogelström of Fogelström's novel, is anything but a naughty sexcapade. It's a film about disaffected youth: Monika and Harry (Lars Ekborg) are in their late teens and trapped in boring jobs. Monika works at a produce store where she is sexually harassed by the male employees, and Harry, a packer and delivery boy in a store that deals in pottery and glassware, is constantly being scolded for being late and lazy. Harry wants to study to be an engineer, but he has to look after his father, who is an invalid. His mother died when he was 8, and he tells Monika that he has always felt alone. Monika is anything but alone: Her father is abusive and her mother barely tends to Monika's noisy young siblings. So when Harry's father goes into a hospital, Monika persuades Harry to run away with her. They steal his father's boat and sail away from Stockholm to the countryside, beautifully filmed by Gunnar Fischer. Their idyll is eventually cut short by their lack of money and Monika's pregnancy. The problem with the film is that a rather puritanical tone eventually seeps in, making Monika the focus of a moral condescension that Bergman would outgrow as his career progressed.

| Promotional posters for the 1955 American release of Summer With Monika |

Mon Oncle Antoine (Claude Jutra, 1971)

The title of Claude Jutra's richly textured film seems to promise a coming-of-age story, which is what, eventually, it delivers. But first the film acquaints us with a Quebec asbestos mining town in the 1940s. The first event we witness is a fight between a miner, Jos Poulin (Lionel Villeneuve), and his boss (Georges Alexander), which is hardly a fight at all because the boss speaks English and Jos doesn't, which easily allows him to ignore what the boss is saying and do what he wants to do: quit the mine and go look for work elsewhere. Our first look at Antoine (Jean Duceppe) is when he's doing his work as the town's undertaker: a comically macabre scene in which the corpse is denuded of the "suit" he was wearing for the viewing, which turns out to be a false front quickly plucked off the naked body and saved for another corpse, and the rosary is untwined from his stiffening fingers. Antoine is the owner, with his wife, Cecile (Olivette Thibault), of the town's general store, which employs his teenage nephew, Benoit (Jacques Gagnon); a teen girl, Carmen (Lyne Champagne), who lives at the store because her skinflint father (Benoit Marcoux), who pockets her earnings, doesn't want to pay for her upkeep; and Fernand (Jutra), who clerks at the store. It's Christmas time, though there's not much sentiment in the film's treatment of the holiday. One of the best scenes in the movie comes when the mine boss rides through the town in a little two-wheeled cart, tossing cheap gifts to the children as the grownups frown at his stinginess and comment that he hasn't given out any raises or bonuses. Benoit and a friend throw snowballs at the horse, causing the boss to beat a hasty retreat. One of the most celebrated of Canadian films, Mon Oncle Antoine benefits from Jutra's adaptation with Clément Perron of Perron's story, and from Michel Brault's cinematography, but most of all from the great credibility of its cast.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

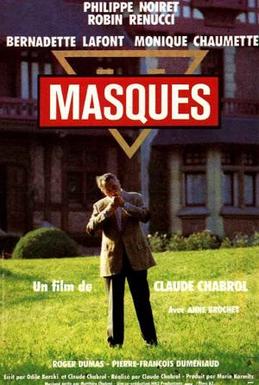

Masques (Claude Chabrol, 1987)

Masques shares the style (and the one-word title) of those 1960s romantic thrillers like Charade (Stanley Donen, 1963), Arabesque (Stanley Donen, 1966), and Kaleidoscope (Jack Smight, 1966) that inevitably got called "Hitchcockian." So it's not surprising that Chabrol, who recognized Hitchcock's genius when Hollywood still thought of him as just a popular entertainer, should cast an hommage to the director in their manner. Roland Wolf (Robin Renucci) is writing a biography of Christian Legagneur (Philippe Noiret), who hosts a cheesy TV talent/game show featuring senior citizens, so he comes to spend a week at Legagneur's estate near Paris. There he's introduced to a houseful of eccentrics: Legagneur's mute chauffeur/cook, Max (Pierre-François Dumeniaud); his secretary, Colette (Monique Chaumette); and a couple, Manu (Roger Dumas), a wine connoisseur who is helping stock Legagneur's cellar, and his wife (or perhaps mistress), who is a masseuse and reads tarot cards (Bernadette Lafont). (Lafont gets third billing after Noiret and Renucci, though hers is decided a secondary role, perhaps because she appeared in Chabrol's first film, Le Beau Serge, in 1958, and worked with him again several times during their long careers.) But most intriguing of all to Wolf is Legagneur's pretty young goddaughter, Catherine (Anne Brochet), who Wolf is told is recovering from a serious illness and is quite fragile. It's clear to the audience from Catherine's erratic behavior that she's drugged -- whether as part of her therapy or not is the question raised in Wolf's mind. For no one in this household is exactly what they seem, least of all Wolf, who, when he's alone in his room, removes a gun from his shaving kit and hides it on a shelf. On the shelf he finds a lipstick and with it, murmuring "Madeleine," he writes a large "M" on a mirror, then rubs it out. Madeleine, we will learn, is Wolf's sister, who is said to have quarreled with Catherine and then left on a trip to the Seychelles, which Wolf seriously doubts. Madeleine is also, of course, the name of the character played by Kim Novak in Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958), one of several "Easter eggs" for Hitchcockians left by Chabrol in the film. Legagneur's TV show, for another example, uses as theme music Gounod's "Funeral March for a Marionette," which was the theme music for Hitchcock's own TV show. Masques failed to find an American distributor when it was first released, but is now available on video. It's definitely minor Chabrol, but Noiret is terrific as the affably sinister Legagneur.

Monday, December 28, 2015

La Cérémonie (Claude Chabrol, 1995)

|

| Valentin Merlet, Jacqueline Bisset, Virginie Ledoyen, and Jean-Pierre Cassel in La Cérémonie |

Sophie: Sandrine Bonnaire

Georges Lelièvre: Jean-Pierre Cassel

Catherine Lelièvre: Jacqueline Bisset

Melinda: Virginie Ledoyen

Gilles: Valentine Merlet

Jérémie: Julien Rochefort

Mme. Lantier: Dominique Frot

Priest: Jean-François Perrier

Director: Claude Chabrol

Screenplay: Claude Chabrol, Caroline Eliacheff

Based on a novel by Ruth Rendell

Cinematography: Bernard Zitzerman

Production design: Daniel Mercier

Film editing: Monique Fardoulis

Music: Matthieu Chabrol

Claude Chabrol's La Cérémonie begins with a long tracking shot through the window of a café, picking up Sophie as she walks toward her appointment with Catherine Lelièvre. Catherine is as chic as Sophie, boyishly dressed with her hair cut in too-short bangs, is drab. The Lelièvres need a housekeeper, Catherine tells her, and Sophie presents the letter of reference from her most recent employer. The interview is slightly awkward, partly because Sophie is oddly oblique in her answers. But Catherine has a large house in a remote location and she needs a housekeeper right away. When Catherine drives Sophie to the house, a young woman named Jeanne appears and hitches a ride to the village near the Lelièvres house; Jeanne, who is as brashly forward as Sophie is reserved, works in the village post office. At the house, Sophie meets Catherine's husband, Georges, a rather blustery businessman, and her son from a previous marriage, the teenage Gilles, and stepdaughter, a university student named Melinda. Sophie proves to be an excellent cook and a reliable maid-of-all-work, but we soon discover that she has a secret or two. One is that she's illiterate, the result of a profound dyslexia. She doesn't drive, being unable to pass a driving test, and pretends that she needs glasses. When Georges insists on taking her to an optometrist, she ducks out of the appointment and buys a cheap pair of drugstore glasses -- though even then she is unable to give the sales clerk the exact change. Waiting for Georges, she meets Jeanne again, and the two women strike up a friendship. Jeanne, it turns out, knows another secret of Sophie's, which is that she was accused of setting fire to her house, killing her disabled father. Jeanne herself was accused of abusing her daughter, born out of wedlock, and causing her death, but both women were acquitted for lack of evidence. And so the stage is set for a story of folie à deux that Chabrol and Caroline Eliacheff adapted from a novel, A Judgment in Stone, by Ruth Rendell. Bonnaire and Huppert are extraordinary in their contrasting styles: Bonnaire passive, almost autistic in manner, Huppert bold and outgoing. The climax, in which a frenzied Jeanne releases Sophie's pent-up hostility, is shattering.

Story of Women (Claude Chabrol, 1988)

"Women's business," according to the subtitle, is what Marie Latour (Isabelle Huppert) tells her husband (François Cluzet) is going on behind closed doors in their apartment. The business is abortion, which Marie provides for prostitutes and other women who are finding childbirth to be a burden during the German occupation of France. But "Women's Business" might also be an apt translation of the original title of Chabrol's film, Une Affaire de Femmes. Based on the true story of Marie-Louise Giraud, who went to the guillotine in 1943 for the abortions she had induced, Story of Women is a deeply feminist film, though never a preachy one. Huppert, as usual, gives an extraordinary performance, emphasizing not only her character's determination to do what she thinks is right for the women she knows, but also her profoundly fatal naïveté about the politics of the era in which she is living. "Women's business" is to survive the ignorance and brutality of men, by any means necessary, but it betrays Marie into some choices that a woman with more knowledge of the way the world works might avoid. She loses sight of the fact that she became an abortionist to survive the deprivation that threatens her life and that of her children, and becomes fixated on their greatly improved standard of living and the possibility that she might earn enough to fulfill her dream of becoming a professional singer. (A distant dream, as her performance of a song in an audition for a music teacher suggests.) In the end, she goes to a guillotine that is not the toweringly glamorous instrument of death we've grown accustomed to from films about the French Revolution, but a grim and shabby little affair cobbled together from plywood and sheet metal -- a fitting image for the shabbiness of the Vichy régime and its treatment of those it saw as a threat.

Sunday, December 27, 2015

Le Beau Serge (Claude Chabrol, 1958)

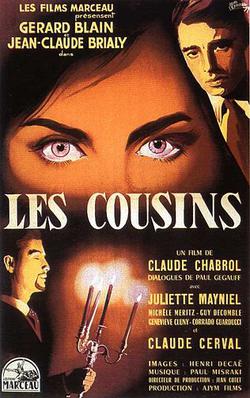

Le Beau Serge has been called the first film of the French New Wave because it was made before the first features by Claude Chabrol's fellow Cahiers du Cinéma critics, François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (1960). The two later films were bigger successes internationally, but the influence of Chabrol's debut on the look, the narrative, and the technique of film continued to be felt, and his next movie, Les Cousins (1959), established Chabrol's reputation. Like Truffaut and Godard, who made international stars of Jean-Pierre Léaud and Jean-Paul Belmondo with their features, Chabrol launched the careers of Gérard Blain and Jean-Claude Brialy, who appeared in his first two films. In Le Beau Serge, Blain plays the title role, a young man who, by staying in his provincial village (Chabrol's own home town of Sardent), becomes an alcoholic layabout, trapped in an unhappy marriage. Brialy plays François, an old friend of Serge's, who left Sardent and became a success, but now returns home after a long absence to recuperate from a lung ailment. The roles are striking in both the similarity to and the differences from the ones Blain and Brialy play in Les Cousins, which takes place in Paris, where Blain is the strait-laced provincial and Brialy is his dissipated cousin. Le Beau Serge follows François's somewhat misguided attempt to help Serge clean up his life, which is complicated when François begins an affair with Serge's sister-in-law, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). In the climax of the film, Serge's wife, Yvonne (Michèle Méritz), goes into labor with the child everyone in the village expects to be deformed or stillborn, as their first child was. In a howling snowstorm, François takes it on himself to go in search of the village's doctor, and then looks for Serge, who is sleeping off a drunk in a chicken coop. The concluding scene, of Serge convulsed in hysterical laughter, is profoundly ambiguous. Chabrol's use of the actual village of Sardent, including many of its townspeople as actors, is brilliantly done, greatly aided by Henri Decaë's cinematography. Les Cousins is a more sophisticated and satisfying film, but it really has to be seen in tandem with Le Beau Serge. Both actors are terrific, but Blain attracted more attention because of his supposed resemblance in both looks and style to James Dean, though to my mind he recalls Montgomery Clift more than Dean.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959)

Chekhov's gun plays a major role in Les Cousins, heightening the suspense about who will use it on whom. But the film isn't a suspense thriller, despite Chabrol's admiration for Hitchcock, so much as it is a deliciously perverse adaption of some classic fables: the country mouse and the city mouse, and the ant and the grasshopper. It also resonates ironically with Balzac's Lost Illusions, the novel that a bookseller (Guy Decomble) allows Charles (Gérard Blain) to "steal" from his shop. In the Balzac novel, a young man from the provinces goes to Paris to seek fame, fortune, and love, and his misadventures wreak havoc on himself and the people he loves. In Les Cousins, country mouse/ant Charles goes to Paris to share an apartment with his cousin, Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy), the city mouse/grasshopper, while both study law. Paul is a somewhat decadent hedonist, who tries to introduce the straiter-laced Charles, who is very much dedicated to his mother back home, to the delights of the city. One of these delights is the promiscuous Florence (Juliette Mayniel), with whom Charles falls in love, only to have things end badly when she chooses to live with Paul instead. Chabrol fills the movie with quirky, somewhat sinister characters, though never turns the film into a clear-cut tale of good vs. evil. Innocence doesn't triumph over cynicism here, though cynicism pays a price, which is what makes Chabrol's film such a grandly satisfying one to watch and to think about afterward. Blain and Brialy (in a suitably Mephistophelean mustache and beard) are brilliant, and the cinematographer, Henri Decaë, gives us a grand evocation of Paris in the 1950s.

Friday, December 25, 2015

Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957)

What do Sweet Smell of Success, His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940), Sullivan's Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941), and The Searchers (John Ford, 1956) have in common? They are all among the critically acclaimed films that, among other honors, have been selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. And none of them received a single nomination in any category for the Academy Awards. Sweet Smell is, of course, a wickedly cynical film about two of the most egregious anti-heroes, New York newspaper columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster) and press agent Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), ever to appear in a film. They make the gangsters of Francis Ford Coppola's and Martin Scorsese's films look like Boy Scouts. So given the inclination of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to stay on the good side of columnists and publicists, we might expect it to shy away from honoring the film with Oscars. But consider the categories in which it might have been nominated. The best picture Oscar for 1957 went to The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean), a respectable choice, and Sidney Lumet's tensely entertaining 12 Angry Men certainly deserved the nomination it received. But in what ways are the other nominees -- Peyton Place (Mark Robson), Sayonara (Joshua Logan), and Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder) -- superior to Sweet Smell? The best actor Oscar winner was Alec Guinness for The Bridge on the River Kwai, another plausible choice. But Tony Curtis gave the performance of his career as Sidney Falco, overcoming his "pretty boy" image -- in fact, the film makes fun of it: One character refers to him as "Eyelashes" -- by digging deep into his roots growing up in The Bronx. Burt Lancaster would win an Oscar three years later for Elmer Gantry (Richard Brooks), a more showy but less controlled performance than the one he gives here. Either or both of them would have been better nominees than Marlon Brando was for his lazy turn in Sayonara, Anthony Franciosa in A Hatful of Rain (Fred Zinnemann), Charles Laughton in Witness for the Prosecution, and Anthony Quinn in Wild Is the Wind (George Cukor). The dialogue provided by Clifford Odets and Ernest Lehman for the film crackles and stings -- there is probably no more quotable, or stolen from, screenplay, yet it went unnominated. So did James Wong Howe's eloquent black-and-white cinematography, showing off the neon-lighted Broadway in a sinister fashion, and Elmer Bernstein's atmospheric score mixed well with the jazz sequences featuring the Chico Hamilton Quintet. Even the performers in the film who probably didn't merit nominations make solid contributions: Martin Milner is miscast as the jazz musician who falls for Hunsecker's sister (Susan Harrison), but he hasn't yet fallen into the blandness of his famous TV roles on Route 66 and Adam-12, and Barbara Nichols, who had a long career playing floozies in movies and on TV, is surprisingly touching as Rita, one of the pawns Sidney uses to get ahead. As a director, Alexander Mackendrick is best known for the comedies he did at Britain's Ealing Studios with Alec Guinness, The Man in the White Suit (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955). His work on Sweet Smell was complicated by clashes with Lancaster, who was one of the film's executive producers, and after making a few more films he accepted a position as dean of the film school at the California Institute of the Arts in 1967, where he spent the rest of his career as an instructor after resigning his administrative position. Sweet Smell currently has a 98% favorable rating on Rotten Tomatoes's Tomatometer and an 8.2 rating on the IMDb.

Niagara (Henry Hathaway, 1953)

Niagara was one of three movies starring Marilyn Monroe that were released in 1953. The other two, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks) and How to Marry a Millionaire (Jean Negulesco), were hits, confirming what we now know: that Monroe was a peerless comedian, not, as Niagara wants her to be, a film noir siren. She had done earlier turns in legitimate film noir, a small role in The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950), larger ones in Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952) and Don't Bother to Knock (Roy Ward Baker, 1952), so this time 20th Century-Fox decided to go all out in exploiting her as a femme fatale. There are many things wrong with Niagara, one thing being that it can't quite decide whether it's a noir thriller or a Technicolor travelogue about the eponymous falls and their various tourist attractions. But what's most wrong about it is its misuse of Monroe, who is not even the real lead character in the film: Her role is decidedly secondary to that of Jean Peters. And she is grotesquely exploited in her part as Rose Loomis, unhappily married to a mentally unstable man (Joseph Cotten) and plotting to have her lover (Richard Allan) bump him off. The studio can't resist dressing her in skin-tight clothes, with high heels that make it impossible for her to walk without bumps and grinds, and flaming red lipstick that's obviously freshly put on even when she's supposed to be waking up in the morning. A producer less under the control of the studio than Charles Brackett (who also wrote the clunky screenplay with Walter Reisch and Richard L. Breen) might have made Rose into a credible character, but here she's only an adolescent boy's fantasy. But even a misused Marilyn is better than no Marilyn at all, as we find out two-thirds of the way through the movie when the focus shifts to the character played by Peters and her grinning ass of a husband (Max Showalter), and we have nothing to marvel at but the Falls. If the screenplay had fallen into the hands of a Hitchcock, Niagara might have been a success, but Henry Hathaway directs as if he's bored by the whole thing.

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

|

| Diane Keaton and Woody Allen in Annie Hall |

Annie Hall: Diane Keaton

Rob: Tony Roberts

Allison: Carol Kane

Tony Lacey: Paul Simon

Pam: Shelley Duvall

Robin: Janet Margolin

Mom Hall: Colleen Dewhurst

Duane Hall: Christopher Walken

Director: Woody Allen

Screenplay: Woody Allen, Marshall Brickman

Cinematography: Gordon Willis

Costume design: Ruth Morley

Annie Hall is generally recognized as the movie that took Woody Allen from being a mere maker of comedy films like Bananas (1971) and Sleeper (1973) that were extensions of his persona as a stand-up comedian and into his current status as a full-fledged auteur, with a record-setting 16 Oscar nominations as screenwriter, along with seven nominations as director (the same number as Steven Spielberg, and only one less than Martin Scorsese). It is one of the few outright funny movies to have won the best picture, and also won for Diane Keaton's performance and Allen's direction and screenplay. Watching it today, in the light of his later work, I still find it fresh and original and frankly more satisfying than most of his later films. Marshall Brickman shared the screenwriting Oscar for Annie Hall and was also nominated along with Allen for the screenplay of Manhattan (1979), as was Douglas McGrath for Bullets Over Broadway (1995), one of his most entertaining later movies. Is it possible that Allen should have worked with a collaborator more often? Would that have curbed his tendency to overload his movies with existentialist conundrums and his increasingly creepy fascination with much younger women -- viz., Emma Stone in Irrational Man (2015) and Magic in the Moonlight (2014), Evan Rachel Wood in Whatever Works (2009), and Scarlett Johansson in Scoop (2006) and Match Point (2005)? But it does Allen's achievement in Annie Hall a disservice to view the film in light of his later career (and his private life). He made a step, not a leap, forward from the goofy early comedies by playing on his stand-up persona -- the film opens and ends with Alvy Singer (Allen) cracking jokes and includes scenes in which Alvy does stand-up at a rally for Adlai Stevenson and at the University of Wisconsin. What makes the movie different from the "early, funny ones" -- as a rueful running gag line goes in Stardust Memories (1980) -- is his willingness and ability to turn Alvy into a real person who just happens to be very funny. Keaton's glorious performance also succeeds in giving dimension to what could have been just a caricature. Annie Hall may not have deserved the best picture Oscar in a year that also saw the debut of Star Wars, Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Luis Buñuel's That Obscure Object of Desire, but it's easy to make a case for it.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003)

|

| Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson in Lost in Translation |

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Twenty-Four Eyes (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1954)

One of the most unabashedly sentimental movies you'll ever see, Twenty-Four Eyes may also be one of the most effective anti-war movies, without presenting bloody scenes of people being killed and maimed. Hideko Takamine plays Oishi, a young teacher who begins her career in 1928 on Shodo Island in the Inland Sea of Japan, teaching a first-grade class of 12 -- six boys and six girls -- the 24 eyes of the film's title. We follow her life, and through her point of view the lives (and some deaths) of her first pupils, for the next 18 years, as the world and the war encroach upon a peaceful, pastoral setting. Where Kinoshita's Morning for the Osone Family (1946) was claustrophobic in its presentation of life during wartime, Twenty-Four Eyes shows how the entrapment of people by war can occur in a place where there are no visible signs of the conflict. The natural setting remains undisturbed. No planes fly overhead, no bombs are dropped on the village, but the menace of war threatens the minds and hearts of the most vulnerable: the children Oishi teaches. The most chilling scenes are the ones in which young men are sent off to the war, as flag-waving crowds sing bloodthirsty tributes to the glory of dying in battle for their country. Kinoshita and cinematographer Hiroshi Kusuda reinforce the bitter irony by their restraint. They don't darken the atmosphere: It's the same lovely natural setting. Only the human beings in it have changed. I have to admit to feeling the movie is overlong, and that Kinoshita ladles on the pathos a bit too heavily. The cast weeps floods of tears, and the soundtrack features not only the Japanese folk songs that the children learn but also some old-fashioned Western parlor songs: "Annie Laurie," "The Last Rose of Summer," "Home, Sweet Home," "Auld Lang Syne," and, most curiously, "What a Friend We Have in Jesus." But repress the cynic or the realist, and you may find it moving, too.

Morning for the Osone Family (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1946)

|

| Haruko Sugimura, Mitsuko Miura, and Eitaro Ozawa in Morning for the Osone Family |

Ichiro Osone: Toshinosuke Nagao

Taiji Osone: Shin Tokudaiji

Yuko Osone: Mitsuko Miura

Takashi Osone: Shiro Osaka

Issei Osone: Eitaro Ozawa

Sachiko Osone: Natsuko Kahara

Akira Minari: Junji Masuda

Heibei Tanji: Kinji Fujiwa

Ippei Yamaki: Eijiro Tono

Director: Keisuke Kinoshita

Screenplay: Eijiro Hisaita

Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda

Art direction: Mikio Mori

Film editing: Yoshi Sugihara

Music: Takaaki Asai

One of the myths of war is that the enemy moves in lockstep, from the commander-in-chief down to the lowliest citizen. So those of us who are (just barely) old enough to remember something about living through World War II, the myth of Japan as a monolithic force lingers, even though 70 years of peace with the Japanese and a wholesale assimilation by the West of their culture, from sushi to anime, has effaced old hostilities. Morning for the Osone Family gives us a valuable sense of the way things were -- or at least may have been. Made in the year after the surrender of Japan, after ideological censorship had ceased (though the American occupation imposed its own censorship, which is why you'll find no mention of the atomic bomb in Japanese movies made just after the war), Morning for the Osone Family gives us a portrait of what a dissenting family went through during the war. How accurate the portrait may be is up to question -- just as we could question the accuracy of the "home front" movies made in the United States during and after the war. But Kinoshita and screenwriter Eijiro Hisaita give us a plausible account of what might have happened to a widow, Fusako, and her three sons, her daughter, and her brother-in-law in the waning years of the war. One son is imprisoned for writing against the war; the daughter is forced to break off her engagement to a young man because of the political implications of what her brother did; another son, a pacifist who wants to be an artist, is drafted and dies of pneumonia in a hospital; the youngest son, embracing the militarist propaganda, enlists and is killed. And then there is the domineering presence of the brother-in-law, a colonel who despises the way Fusako has raised her children to doubt the glory of the Japanese military. When his house is destroyed by bombing, he moves in with the Osone family and takes over the household. Devastated by the surrender, he begins to stockpile food in their house, even as starvation spreads across the land. The film takes place on a single set, which only emphasizes the sense of a world closing in on the family.

Monday, December 21, 2015

Bardelys the Magnificent (King Vidor, 1926)

This entertaining swashbuckler was long thought to be lost, apparently because of a contractual agreement between MGM and Rafael Sabatini, author of the novel on which it was based. When the studio failed to renew the rights to the novel in 1936, it destroyed the negative and all the prints it could get its hands on. Fortunately, 70 years later a print surfaced in France, missing only one reel that the restorers pieced together with production stills and footage from the original trailer. It was a good save, especially for the legacy of its director, King Vidor, and its star, John Gilbert. Vidor stages several lively swordfights and a memorable love scene in which Bardelys (Gilbert) woos Roxalanne de Lavedan (Eleanor Boardman) in a boat as it passes through the overhanging branches of a willow tree. But the film's highlight is a spectacular escape from the gallows, in which Gilbert (almost certainly with the help of his stunt double) outdoes Douglas Fairbanks in swinging from ropes and curtains, climbing walls, and fencing with pursuers. The story is romantic nonsense in which Bardelys, a womanizing marquis at the court of Louis XIII, makes a wager that he can win the hand of Roxalanne, who has spurned the advances of the very hissable villain, Châtellerault (Roy D'Arcy). To win the bet, Bardelys finds himself assuming the identity of a man he finds dead, Lesperon (played by Theodore von Eltz in the missing reel), an enemy of the king. Sure enough, he and Roxalanne fall in love under the willows, but his imposture not only turns her against him when she finds proof that Lesperon is engaged to someone else, but also puts him in danger of being hanged for treason, especially after Châtellerault turns up and refuses to disclose that Lesperon is really Bardelys. Dorothy Farnum adapted the novel, and the cinematography is by William H. Daniels. The cast supposedly includes the 19-year-old John Wayne as a guard, in only his second film appearance, but good luck spotting him. I didn't.

Sunday, December 20, 2015

In a Lonely Place (Nicholas Ray, 1950)

The "lonely place" is Hollywood, where Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart) is a screenwriter with a barely held-in-check violent streak. This celebrated movie contains one of Bogart's best performances, though it looks and feels like the low-budget production it was. Bogart's own company, Santana, produced it for release through Columbia, instead of Bogart's employer, Warner Bros., which may explain why, apart from Bogart and Gloria Grahame, the supporting cast is so unfamiliar: The best-known face among them is Frank Lovejoy, who plays Bogart's old army buddy, now a police detective. In a Lonely Place seems to be set in a different Hollywood from the one seen in the year's other great noir melodrama, Billy Wilder's Sunset Blvd. There are no movie star cameos and glitzy settings in the Bogart film. What this one has going for it, however, is a haunting, off-beat quality, along with some surprising heat generated between Bogart and Grahame, who plays Laurel Gray, a would-be movie actress with an intriguing, only partly glimpsed past. She has, for example, a rather bullying masseuse (Ruth Gillette), who seems to be a figure out of this past. In fact, the whole film is made up of enigmatic figures, including Steele's closest friends, his agent, Mel Lippman (Art Smith), and an aging alcoholic actor, Charlie Waterman (Robert Warwick). Both of them stick with Steele despite his tendency to fly off the handle: He insults and at one point even slugs the agent, while at another he defends the actor with his fists against an insult. Though the central plot has to do with Steele's being suspected of murdering a hat-check girl (Martha Stewart) he brought to his apartment to tell him the plot of a novel he's supposed to adapt, the film is less a murder mystery than a study of a damaged man and his inability to overcome whatever made him that way. And despite the usual tendency of Hollywood films to end with a resolution by tying up loose ends, In a Lonely Place leaves its characters as tensely enigmatic as they were at the start -- perhaps even more so. The screenplay by Andrew Solt reworked Edmund H. North's adaptation of a novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, with much help from director Ray.

Saturday, December 19, 2015

Romeo and Juliet (Franco Zeffirelli, 1968)

|

| Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey in Romeo and Juliet |

Come, gentle night, come, loving black-brow'd night,And when Juliet is preparing to drink the potion that will simulate death, we get none of her terrors of being sealed in the Capulet tomb. Zeffirelli's version is a safe compromise between the too-reverent George Cukor production for MGM in 1936, and Luhrmann's souped up modern version, but Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey are preferable to the aging Norma Shearer and Leslie Howard, and they handle the verse better than Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes did in Luhrmann's film. One thing the Zeffirelli film also has going for it is Nino Rota's score, which grew over-familiar when it became a best-selling LP but is still evocative today. And there are some good actors in the cast, including Michael York's Tybalt, Pat Heywood's Nurse, and Milo O'Shea's Friar Lawrence, not to mention Laurence Olivier's uncredited narrator. (Olivier also supplied the voice for the Italian actor playing Montague.) But I still want to see Renato Castellani's 1954 film version again -- it's been so long since I saw it that I had forgotten it was in color, and I may in fact have only seen it on a black-and-white TV -- before pronouncing Zeffirelli's film the best movie version.

Give me my Romeo, and, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

Friday, December 18, 2015

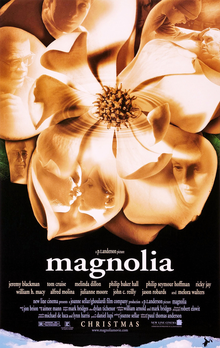

Magnolia (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1999)

I remembered only two things about Magnolia from the first time I saw it: the rain of frogs and Tom Cruise's performance. Now it occurs to me that perhaps I should watch some of Anderson's other films again, especially There Will Be Blood (2007), about which I remember mainly the "milkshake" scene, because there is so much more good stuff going on in Magnolia than I remembered. It has that loose, semi-improvised quality that I have come to admire in Godard, while still lavishing all the resources that the backing of New Line Cinema could afford. On the other hand, I think that the abundance of resources may have undermined the film, because it made possible the two things I did remember, the special-effects frogs and the A-list presence of Cruise, at the expense of the detail work that comes to the fore in my rewatching. I'm talking especially about Philip Seymour Hoffman's touching performance as Jason Robards's nurse, John C. Reilly's naive cop, Melora Walters's scattered druggie, Philip Baker Hall's disintegrating game show host, and Julianne Moore's descent into hysteria. That said, I still appreciate both the frogs and Cruise, who lets out the madness that we had only glimpsed before in his work. The performance earned him an Oscar nomination, as over-the-top and supposedly out-of-character performances tend to do. (We would later, in the Katie Hughes era and as his commitment to Scientology came to the fore, come to wonder how out of character this manic Cruise really was.) I think the movie is too long (it runs 188 minutes), and that perhaps some of its segments exist only because of Anderson's commitment to the actors who made Boogie Nights (1997). I'm thinking here of William H. Macy's character, which seems to me like a dangling thread in the fabric of the film -- though it does result in a wonderful scene in which Macy and Henry Gibson compete for the attention of a hunky bartender (Craig Kvinsland). As for the frogs, I refuse to speculate on their "meaning," preferring the reaction of Stanley (Jeremy Blackman): "This happens. This is something that happens."

Thursday, December 17, 2015

Meet John Doe (Frank Capra, 1941)

|

| Walter Brennan, Gary Cooper, Irving Bacon, Barbara Stanwyck, and James Gleason in Meet John Doe |

Ann Mitchell: Barbara Stanwyck

D.B. Norton: Edward Arnold

The "Colonel": Walter Brennan

Mrs. Mitchell: Spring Byington

Henry Connell: James Gleason

Mayor Lovett: Gene Lockhart

Ted Sheldon: Rod LaRocque

Beany: Irving Bacon

Bert: Regis Toomey

Director: Frank Capra

Screenplay: Robert Riskin

Based on a story by Richard Connell and Robert Presnell Sr.

Cinematography: George Barnes

Art direction: Stephen Goosson

Film editing: Daniel Mandell

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Meet John Doe opens with reporters and editors at a newspaper being fired because the owner wants it to be, as the paper's new slogan says, "streamlined ... for a streamlined age." And the plot involves a very wealthy man who uses a phony populist approach to try to get himself elected president. Who says a 74-year-old movie isn't relevant today? But the movie eventually falls apart because Frank Capra can't get his story to make sense. I never watch a Capra film without wanting to throw something at the screen, and that includes the beloved It's a Wonderful Life (1946), which makes me faintly nauseated. Meet John Doe has a few wonderful things going for it, principally the opportunity to see Barbara Stanwyck and Gary Cooper at their starry prime. (Though they were much better in a movie they made together in the same year, Howard Hawks's Ball of Fire.) Experience tells, and by 1941 Stanwyck had been making movies for more than a decade, and Cooper had been in films since the mid-1920s. They had the kind of easy, spontaneous, natural manner on screen that could steady even the most wobbly vehicle. Meet John Doe starts to wobble about halfway through, when it becomes apparent that there is no easy way Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin can resolve the director's muddled populist sentiments: Capra always wants to celebrate the "common man" in his movies, but it was clear to anyone on the brink of the entry of the United States into World War II that the common man was a dangerous force to work with. So what we have in the film is an odd mix of sentimentality and cynicism. Stanwyck's character, Ann Mitchell, starts as a cynic, concocting a sob story about a "John Doe" who threatens to commit suicide because he's fed up with a corrupt society. She does it to save her job at the newspaper, and the equally cynical managing editor Henry Connell decides to run with it. That's when they find a homeless man (Cooper) to pretend to be the real John Doe. When he turns out to be an inspiration to the "common man" of Capra's fantasies, bringing about peace and harmony across the land, the sentimentality takes over, converting Ann and Connell, but also playing into the hands of the paper's owner, D.B. Norton, who tries to use John Doe's followers for political gain. And when John Doe is exposed as a fake, the adoring millions suddenly turn into a raging mob. If Capra weren't so invested in making things turn out all right, he could have created a powerful satire, but he couldn't find an ending to the film that would satisfy both his Hollywood-nurtured sentimentality and the logic of the plot.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

Cape Fear (Martin Scorsese, 1991)

I don't think I've ever seen J. Lee Thompson's 1962 version of this film, but nothing about Scorsese's version shows me why a director of his skill and stature thought it necessary to remake it. I'm even more puzzled to learn that Steven Spielberg originally planned to film it, but when he decided it wasn't exactly his thing, he traded with Scorsese for the rights to make Schindler's List (1993). (Which in turn makes me wonder what Scorsese's version of List would have been like: Would Robert De Niro have played Oskar Schindler or Amon Goeth?) It's also puzzling that anyone really needed to remake this specific material (James R. Webb's screenplay based on a novel by John D. MacDonald, revised here by Wesley Strick) when the premise of the film, an ex-con takes revenge on the man he blames for sending him to prison, is such a staple of melodrama. The only real twist to the premise is that the object of revenge is not the prosecuting attorney or the judge who sentenced Max Cady (De Niro), but his defense attorney, Sam Bowden (Nick Nolte), who was so revolted by Cady's rape and battery of a young woman that he suppressed evidence of the woman's promiscuity, which he might have used at least to get a lighter sentence for Cady, who learned about the suppressed evidence when he studied law in prison. The Scorsese version is certainly watchable -- Scorsese has yet to make a film that isn't -- but it is what it is: a melodrama ratcheted up to the heights. Scorsese's direction is literally in your face: He has Freddie Francis film some dialogue scenes in closeups, with the camera slowly pulling in even closer on faces as the characters talk. The one time Scorsese decides not to do this is actually the best scene in the film: when Cady talks with Bowden's daughter, Danielle (Juliette Lewis) on the stage of her high school's theater. Here the distance the camera keeps from them at first allows for a tension that grows in intensity, until finally the camera draws nearer. De Niro pulls out all the stops in a performance that earned him an Oscar nomination, but at times verges on self-parody, especially the Southern (?) accent that he adopts (and occasionally drops). Nolte and Jessica Lange (as Leigh, Bowden's wife) are fine, as one expects them to be, but the best performance is given by Lewis, who was 18 and makes Danielle a credible 15-year-old, her rebellious streak reinforcing her attraction to Cady at the same time that she knows to be wary of him. It earned her an Oscar nomination and launched her career. The casting of Robert Mitchum and Gregory Peck, the Cady and Bowden of the first film, in cameo roles is just a gimmick, and not an especially effective one.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

Man Hunt (Fritz Lang, 1941)

Walter Pidgeon spent much of his movie career at MGM, playing prince consort to Greer Garson: He was Mr. Miniver, Mr. Parkington, and M. Curie -- they made nine films together, if you count their cameos as themselves in The Youngest Profession (Edward Buzzell, 1943). So it's interesting to see him on his own in a 20th Century-Fox film, playing an action hero, the big-game hunter Alan Thorndike, who nearly assassinates Hitler, is beaten by the Gestapo, is pushed off a cliff and survives, escapes to a seaport where he boards a freighter for England, eludes his relentless pursuers, goes to ground in a cave, survives by killing his chief antagonist, and at the film's end parachutes into Germany, presumably to start it all over again. In fact, Pidgeon is a little too starchy for the role, which was better suited to someone like Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power, and he's upstaged (as who wasn't?) by George Sanders as the villain. Joan Bennett gives a nice performance as Jerry Stokes, the cockney "seamstress" (read: prostitute) who helps Thorndike escape. There's an entertaining scene in which Jerry encounters Thorndike's snooty sister-in-law, Lady Riseborough (Heather Thatcher). Roddy McDowall makes his American film debut as the cabin boy Vaner. This was the first of four films Bennett made with Fritz Lang as director, and they remain probably the highlights of her long career. Although Lang's American films never reached the heights of the ones he made in Germany, such as M (1931) and Metropolis (1927), he had a sure hand with the kind of suspense on display in Man Hunt. Dudley Nichols did the screenplay based on Geoffrey Household's novel Rogue Male.

Monday, December 14, 2015

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

|

| Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver |

Sunday, December 13, 2015

Oliver Twist (David Lean, 1948)

After George Cukor's 1935 David Copperfield, I think this is my favorite adaptation of Dickens for film or TV, and god knows there have been plenty of them. What Lean does right is to treat the Dickens book as a fable, not a novel. A novel takes its characters seriously as human beings; a fable sees them as embodiments of good and evil. And there's plenty of evil on display in Oliver Twist, from the brute evil of Bill Sikes (Robert Newton) to the venal evil of Fagin (Alec Guinness) to the stupid evil of Mr. Bumble (Francis L. Sullivan) and Mrs. Corney (Mary Clare). Oliver (John Howard Davies) is innocently good, whereas Mr. Brownlow (Henry Stephenson) is a man of good will. Nancy (Kay Walsh) and, to a lesser extent, the Artful Dodger (Anthony Newley) are potentially good people who have been corrupted by evil. We need fables like this from time to time, just to keep ourselves from despair. The performers are all beautifully cast, especially Davies as Oliver: He's just real-looking enough in the role that he doesn't become saccharine, the way some prettier Olivers do. This is Lean in what I think of as his great period, when he was making beautifully filmed movies with just the right measure of sentiment: Brief Encounter (1945) and Great Expectations (1946) in addition to this one. But he would be bit by the epic bug while working on The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), and its success would betray him into bigger but not necessarily better movies: Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), and the rest of his later oeuvre would have the same attention to visual detail that make his early movies so rich, but they seem to me chilly in comparison. Here he benefits not only from a perfect cast, but also from Guy Green's photography of John Bryan's set designs. There are probably few more terrifying scenes in movies than Sikes's murder of Nancy, which sends Sikes's dog (one of the most impressive performances by an animal in movies) into a frenzy. Running it a close second is Sikes's death, seen from a vertiginous rooftop angle. We don't actually see the death, but only the swift tautening of the rope as he plunges, punctuated by a sudden snap. The film is not as well known in America as in Great Britain, where it engendered controversy: Guinness's portrayal of Fagin elicited charges of anti-Semitism, especially since the film appeared so soon after the world learned about the Holocaust. The truth is, Guinness doesn't play to Jewish stereotypes, but Fagin's absurdly exaggerated nose (which makeup artist Stuart Freeborn copied from George Cruikshank's illustrations for the novel) does evoke some of the caricatures in the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer. The film was edited to remove some of the shots of Fagin in profile, and was held from release in the United States until 1951.

Saturday, December 12, 2015

The Wipers Times (Andy De Emmony, 2013)

Friday, December 11, 2015

Hannah and Her Sisters (Woody Allen, 1986)

In the films in which he appears, Woody Allen has two personae: the nebbishy neurotic that was the mainstay of his early career as a standup comedian, and the witty, self-effacing charmer who can credibly win the hearts of such co-stars as Diane Keaton, Mia Farrow, and Dianne Wiest. He appears in both personae in Hannah and Her Sisters. As Mickey, he suffers from hypochondria and a fear of death so severe that when he discovers he doesn't have a brain tumor he goes through a desperate but hilarious search for God, even going so far as to try to convert to Catholicism. (The gag involving Wonder Bread and mayonnaise is, I think, a bit too forced.) He also plays the successful lover, winning Holly (Wiest) after an earlier misfired attempt. But Allen is not the only actor in the film who is playing the two "Woody Allen" personae: As Elliot, who is married to Mickey's ex-wife, Hannah (Farrow), Michael Caine also becomes both the neurotic and the charmer in his obsession with Hannah's sister, Lee (Barbara Hershey). So what we get is Elliot as Mickey's psychological doppelgänger. (Mickey was once married to Hannah and Holly is also her sister, reinforcing the duplication.) That all of this works as well as it does -- and sometimes it doesn't -- is why the film remains one of Allen's most successful. It was a critical and commercial hit, receiving seven Oscar nominations (including best picture) and winning three: for Caine and Wiest as supporting performers and for Allen as writer -- he was also nominated as director. It is certainly well-structured, given the intricacy of the various interrelationships of the three sisters and their husbands and lovers. I think the weakest part of the structure is Allen's own performance; unlike Caine, he never succeeds in integrating the two personae. Some of the problem is the way his role is written: The comedy of his hypochondria is too broad for a film that takes on some serious issues in the way people deal with infatuation and infidelity, and when Mickey recovers from his obsession with God and death, Allen borrows shamelessly from Preston Sturges's great Sullivan's Travels (1941) by having Mickey snap out of it while watching the Marx Brothers in Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933), just as Sullivan recovers from his own funk by watching a Disney cartoon. But there is a real sophistication in the way Allen ends his somewhat Chekhovian comedy by playing on our expectation of a happy ending. All of the characters in the film are far too morally compromised for a simple resolution, so Allen gives us what just appears to be one: a Thanksgiving party with all of the sisters and their husbands accounted for. At the very end, we find that Mickey and Holly are not only married now, but she's pregnant. Fade out, music and credits up. Perhaps only as we're walking out of the theater do we remember that it has earlier been well established that Mickey is infertile.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

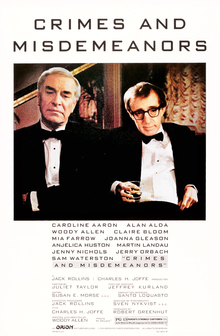

Crimes and Misdemeanors (Woody Allen, 1989)

Crimes and Misdemeanors, a prime example of Woody Allen's mid-career films, has an impressive 8.0 rating on IMDb and a 93% favorable critics' rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Which surprises me, because I don't think it works. By this point, Allen had learned his lesson about trying to emulate Ingmar Bergman with such flops as Another Woman (1988) and September (1987), but he hadn't yet got Bergman out of his system. So what he does in Crimes and Misdemeanors is to try to make a "cinema of ideas" -- in the manner of Bergman or Robert Bresson or Roberto Rossellini's Europa '51 -- while at the same time mocking his own effort to do so. He tells the story of the ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal (Martin Landau), who hires a hit man to kill his mistress (Anjelica Huston), who is threatening to expose their affair to Judah's wife (Claire Bloom). At the same time, Allen also tells the story of Cliff Stern (Allen), a documentary film-maker who wants to deal with serious subject matter but instead is forced to make a movie about his brother-in-law, Lester (Alan Alda), a glib, womanizing TV producer. Both Judah and Cliff are wrestling with the existentialist dilemma: In the absence of God, how do we determine what is right? Judah suffers pangs of guilt for his crime, recalling the fear of God placed in him by his Jewish upbringing, but he gets away with the murder and has evidently smothered his guilt by intellectually justifying it. Cliff meets and falls in love with Lester's charming associate producer, Halley (Mia Farrow), who is enthusiastic about the project Cliff has been working on: a profile of a philosopher, Louis Levy (Martin Bergmann), who has experienced suffering and worked his way to an apparent affirmation of life. But Cliff is fired after submitting a scathing first cut of the film about Lester, in which the producer is portrayed as Mussolini and as Francis, the talking mule. Then the life-affirming philosopher commits suicide, putting an end to Cliff's "serious" project. Judah and Cliff come together at the wedding of the daughter of Cliff's other brother-in-law, a rabbi named Ben (Sam Waterston), who happens to be one of Judah's patients and has been going blind throughout the film, accepting it as God's will. After telling Cliff his "idea" for a film -- essentially his own story -- and discussing the moral implications, Judah walks off happily with his wife, leaving Cliff, who has just heard Lester announce his engagement to Halley, very much alone. Yes, the ironies are as thick and heavy as that. There are strong performances from all the principals, including Jerry Orbach as Judah's brother, who arranges the hit, and Landau received a well-deserved supporting actor Oscar nomination. Allen's nominations as director and screenwriter are more iffy: He seems to me more an animator of ideas and ironies than a creator of living human beings.

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

The World of Apu (Satyajit Ray, 1959)

|

| Soumitra Chatterjee in The World of Apu |

Aparna: Sharmila Tagore

Pulu: Swapan Mukherjee

Kajal: Alok Chakravarty

Sasinarayan: Dhiresh Majumdar

Landlord: Dhiren Ghosh

Director: Satyajit Ray

Screenplay: Satyajit Ray

Based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay

Cinematography: Subrata Mitra

Music: Ravi Shankar

The exquisite conclusion to Ray's trilogy takes Apu into manhood. He leaves school, unable to afford to continue into university, and begins to support himself by tutoring while trying to write a novel. When his friend Pulu persuades him to go along to the wedding of his cousin, Aparna, Apu finds himself marrying her: The intended bridegroom turns out to be insane, and when her father and the other villagers insist that the astrological signs indicate that Aparna must marry someone, Apu, the only available male, is persuaded, even though he regards the whole situation as nonsensical superstition, to take on the role of bridegroom. (It's a tribute to both the director and the actors that this plot turn makes complete sense in the context of the film.) After a wonderfully awkward scene in which Apu and Aparna meet for the first time, and another in which Aparna, who has been raised in comparative luxury, comes to terms with the reality of Apu's one-room apartment, the two fall deeply in love. But having returned to her family home for a visit, Aparna dies in childbirth. Apu refuses to see his son, Kajal, blaming him for Aparna's death and leaving him in the care of the boy's grandfather. He spends the next five years wandering, working for a while in a coal mine, until Pulu finds him and persuades him to see the child. As with Pather Panchali and Aparajito, The World of Apu (aka Apur Sansar) stands alone, its story complete in itself. But it also works beautifully as part of a trilogy. Apu's story often echoes that of his own father, whose desire to become a writer sometimes set him at odds with his family. When, in Pather Panchali, Apu's father returns from a long absence to find his daughter dead and his ancestral home in ruins, he burns the manuscripts of the plays he had tried to write. Apu, during his wanderings after Aparna's death, flings the manuscript of the novel he had been writing to the winds. And just as the railroad train figures as a symbol of the wider world in Pather Panchali, and as the means to escape into it in Aparajito, it plays a role in The World of Apu. Instead of being a remote entity, it's present in Apu's own backyard: His Calcutta apartment looks out onto the railyards of the city. Adjusting to life with Apu, Aparna at one point has to cover her ears at the whistle of a train. Apu's last sight of her is as she boards a train to visit her family. And when he reunites with his son, he tries to play with the boy and a model train engine. The glory of this film is that it has a "happy ending" that is, unlike most of them, completely earned and doesn't fall into false sentiment. I don't use the world "masterpiece" lightly, but The World of Apu, both alone and with its companion films, seems to me to merit it.

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

Aparajito (Satyajit Ray, 1956)

|

| Smaran Ghosal in Aparajito |

Apu as an adolescent: Smaran Ghosal

Harihar, Apu's father: Kanu Bannerjee

Sarbajaya, Apu's mother: Karuna Bannerjee

Bhabataran, Apu's great uncle: Ramani Sengupta

Nanda: Charuprakash Ghosh

Headmaster: Subodh Ganguli

Director: Satyajit Ray

Screenplay: Satayajit Ray, Kanaili Basu

Based on a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bannerjee

Cinematography: Subrata Mitra

Music: Ravi Shankar

As the middle film of a trilogy, Aparajito could have been merely transitional -- think for example of the middle film in The Lord of the Rings trilogy: The Two Towers (Peter Jackson, 2002), which lacks both the tension of a story forming and the release of one ending. But Ray's film stands by itself, as one of the great films about adolescence, that coming-together of a personality. The "Apu trilogy," like its source, the novels by Bibhutibhushan Bannerjee, is a Bildungsroman, a novel of ... well, the German Bildung can be translated as "education" or "development" or even "personal growth." In Aparajito, the boy Apu (Pinaki Sengupta) sprouts into the adolescent Apu (Smaran Ghosal), as his family moves from their Bengal village to the city of Benares (Varanasi), where Apu's father continues to work as a priest, while his mother supplements their income as a maid and cook in their apartment house. When his father dies, Apu and his mother move to the village Mansapota, where she works for her uncle and Apu begins to train to follow his father's profession of priest. But the ever-restless Apu persuades his mother to let him attend the village school, where he excels, eventually winning a scholarship to study in Calcutta. In Pather Panchali (1955), the distant train was a symbol for Apu and his sister, Durga, of a world outside; now Apu takes a train into that world, not without the painful but necessary break with his mother. Karuna Banerjee's portrayal of the mother's heartbreak as she releases her son into the world is unforgettable. Whereas Pather Panchali clung to a limited setting, the decaying home and village of Apu's childhood, the richness of Aparajito lies in its use of various settings: the steep stairs that Apu's father descends and ascends to practice his priestly duties on the Benares riverfront, the isolated village of Mansapota, and the crowded streets of Calcutta, all of them magnificently captured by Subrata Mitra's cinematogaphy.

Monday, December 7, 2015

Pather Panchali (Satyajit Ray, 1955)

When I first saw Pather Panchali I was in my early 20s and unprepared for anything so foreign to my experience either in life or in movies. And as is usual at that age, my response was to mock. So half a century passed, and when I saw it again a few months ago, both the world and I had changed. Now I've watched it again, because Turner Classic Movies scheduled it as part of a showing of the entire "Apu trilogy," and I wanted to see it in context with the other two films in the series, which I hadn't seen. It is, of course, a transformative experience -- even for one whom the years have transformed. What it shows us is both alien and familiar, and I wonder how I could have missed its resonance with the Southern poverty that I had witnessed in my own childhood: the significance of family, the problems consequent on adherence to a social code, the universal effect of wonder and fear of the unknown, the necessity of art, and so on. Central to it all is Ray's vision of the subject matter and the essential participation of Ravi Shankar's music and Subrata Mitra's cinematography. And of course the extraordinary performances: Kanu Bannerjee as the feckless, deluded father, clinging to a role no longer relevant in his world; Karuna Bannerjee as the long-suffering mother; Uma Das Gupta as Durga, the fated, slightly rebellious daughter; the fascinating Chunibala Devi as the aged "Auntie"; and 8-year-old Subir Banerjee as the wide-eyed Apu. It's still not an immediately accessible film, even for sophisticated Western viewers, but it will always be an essential one, not only as a landmark in the history of movie-making but also as an eye-opening human document of the sort that these fractious times need more than ever.

Saturday, December 5, 2015

The White Sheik (Federico Fellini, 1952)

This antic comedy was Fellini's first solo feature, based on a story by, believe it or not, Michelangelo Antonioni, collaborating with Fellini and Tullio Pinelli. Ennio Flaiano joined Fellini and Pinelli to write the screenplay, which is about a young couple from the provinces honeymooning in Rome. The husband, Ivan Cavalli (Leopoldo Trieste), doesn't know that his new wife, Wanda (Brunella Bovo), is an ardent fan of a fotoromanzo (a magazine serial that tells a story in photographs). When Wanda finds out that the serial, The White Sheik, is produced just around the corner from the hotel where she and Ivan are staying, she sneaks out in hopes of meeting Fernando Rivoli (Alberto Sordi), the actor who stars in the series as the sheik. Meanwhile, Ivan has scheduled their stay in Rome, including an audience with the pope, down to the minute, so when his family gathers to join the newlyweds and Ivan discovers that she has disappeared, madness ensues. Wanda finds herself swept up by the company photographing the next installment of the series and being wooed by the lecherous Rivoli himself. Ivan indulges in frantic attempts to cover up his wife's absence. Eventually he meets up with the prostitute Cabiria (Giulietta Masina), whose story Fellini will tell five years later in Nights of Cabiria (1957). For a first feature on his own, The White Sheik is remarkable, though it was quickly overshadowed by his next one, I Vitelloni (1953), which also featured Trieste in its cast. The White Sheik was only the second film for Trieste, who had appeared in a small role in Shamed (Giovanni Paolucci, 1947), for which he wrote the screenplay. He proved to be such an impressive character actor that he had a long career, with roles in such movies as Cinema Paradiso (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988), The Name of the Rose (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1986), and The Godfather: Part II (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974).

Friday, December 4, 2015

Marie Antoinette (W.S. Van Dyke, 1938)

|

| Robert Morley and Norma Shearer in Marie Antoinette |

Count Axel de Fersen: Tyrone Power

King Louis XV: John Barrymore

King Louis XVI: Robert Morley

Princesse de Lamballe: Anita Louise

Duke d'Orléans; Joseph Schildkraut

Mme du Barry: Gladys George

Count de Mercey: Henry Stephenson

Director: W.S. Van Dyke

Screenplay: Claudine West, Donald Ogden Stewart, Ernest Vajda

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Art direction: Cedric Gibbons

Film editing: Robert Kern

Costume design: Adrian, Gile Steele

Music: Herbert Stothart

Hollywood historical hokum, W.S. Van Dyke's Marie Antoinette was a vehicle for Norma Shearer that had been planned for her by her husband, Irving G. Thalberg, who died in 1936. MGM stuck with it because as Thalberg's heir, Shearer had control of a large chunk of stock. It also gave her a part that ran the gamut from the fresh and bubbly teenage Austrian archduchess thrilled at the arranged marriage to the future Louis XVI, to the drab, worn figure riding in a tumbril to the guillotine. Considering that it takes place in one of the most interesting periods in history, it could have been a true epic if screenwriters Claudine West, Donald Ogden Stewart, and Ernest Vajda (with uncredited help from several other hands, including F. Scott Fitzgerald) hadn't been pressured to turn it into a love story between Marie and the Swedish Count Axel Fersen. But the portrayal of their affair was stifled by the Production Code's squeamishness about sex, and the long period in which Marie and Louis fail to consummate their marriage lurks unexplained in the background. MGM threw lots of money at the film to compensate: Shearer sashays around in Adrian gowns with panniers out to here, with wigs up to there, and on sets designed and decorated by Cedric Gibbons and Henry Grace that make the real Versailles look puny. The problem is that nothing like a genuine human emotion appears on the screen, and the perceived necessity of glamorizing the aristocrats turns the French Revolution on its head. The cast of thousands includes John Barrymore as Louis XV, Gladys George as Madame du Barry, and Joseph Schildkraut (with what looks like Jean Harlow's eyebrows and Joan Crawford's lipstick) as the foppish Duke of Orléans. The best performance in the movie comes from Morley, who took the role after the first choice, Charles Laughton, proved unavailable; Morley earned a supporting actor Oscar nomination for his film debut. With the exception of The Women (George Cukor, 1939), in which she is upstaged by her old rival Joan Crawford, this is Shearer's last film of consequence. When she turned 40 in 1942, she retired from the movies and lived in increasing seclusion until her death, 41 years later. It says something about Shearer's status in Hollywood that Greta Garbo, who retired at about the same time, and who also sought to be left alone, was the more legendary figure and was more ardently pursued by gossips and paparazzi.

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Duel in the Sun (King Vidor, 1946)

|

| Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones in Duel in the Sun |

Lewt McCanles: Gregory Peck

Jesse McCanles: Joseph Cotten

Senator Jackson McCanles: Lionel Barrymore

Scott Chavez: Herbert Marshall

Laura Belle McCanles: Lillian Gish

The Sinkiller: Walter Huston

Sam Pierce: Charles Bickford

Lem Smoot: Harry Carey

Mrs. Chavez: Tilly Losch

Vashti: Butterfly McQueen

Director: King Vidor

Screenplay: David O. Selznick, Oliver H.P. Garrett

Based on a novel by Niven Busch

Cinematography: Lee Garmes, Ray Rennahan, Harold Rosson

Production design: J. McMillan Johnson

Film editing: Hal C. Kern

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

This is a bad movie, but it's one distinguished in the annals of bad movies because it was made by David O. Selznick, who as the poster shouts at you was "The Producer Who Gave You 'GONE WITH THE WIND.'" Selznick made it to showcase Jennifer Jones, the actress who won an Oscar as the saintly Bernadette of Lourdes in The Song of Bernadette (Henry King, 1943). Selznick, who left his wife for Jones, wanted to demonstrate that she was capable of much more than the sweetly gentle piety of Bernadette, so he cast her as the sultry Pearl Chavez in this adaptation (credited to Selznick himself along with Oliver H.P. Garrett, with some uncredited help by Ben Hecht) of the novel by Niven Busch. Opposite Jones, Selznick cast Gregory Peck as the amoral cowboy Lewt McCanles, who shares a self-destructive passion with Pearl. Both actors are radically miscast. Jones does a lot of eye- and teeth-flashing as Pearl, while Peck's usual good-guy persona undermines his attempts to play rapaciously sexy. The plot is one of those familiar Western tropes: good brother Jesse against bad 'un Lewt, reflecting the ill-matched personalities of their parents, the tough old cattle baron Jackson McCanles and his gentle (and genteel) wife, Laura Belle. Pearl is an orphan, the improbable daughter of an improbable couple, the educated Scott Chavez and a sexy Indian woman, who angers him by fooling around with another man. Chavez kills both his wife and her lover and is hanged for it, so Pearl is sent to live with the McCanleses -- Laura Belle is Chavez's second cousin and old sweetheart -- on their Texas ranch. It's all pretentiously packaged by Selznick: not many other movies begin with both a "Prelude" and an "Overture," composed by Dimitri Tiomkin in the best overblown Hollywood style. It has Technicolor as lurid as its story, shot by three major cinematographers, Lee Garmes, Ray Rennahan, and Harold Rosson. But any attempt to generate real heat between Jones and Peck was quickly stifled by the Production Code, which even forced Selznick to introduce a voiceover at the beginning to explain that the character of the frontier preacher known as "The Sinkiller" (entertainingly played by Walter Huston) was not intended to be a representative clergyman. There are a few good moments, including an impressive tracking shot at the barbecue on the ranch in which various guests offer their opinions of Pearl, the McCanles brothers, and other things. Whether this scene can be credited to director King Vidor, who was certainly capable of it, is an open question, because Vidor found working with the obsessive Selznick so difficult that he quit the film. Selznick directed some scenes, as did Otto Brower, William Dieterle, Sidney Franklin, William Cameron Menzies, and Josef von Sternberg, all uncredited. The resulting melange is not unwatchable, thanks to a few good performances (Huston, Charles Bickford, Harry Carey), and perhaps also to some really terrible ones (Lionel Barrymore at his most florid and Butterfly McQueen repeating her fluttery air-headedness from GWTW).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)