A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Wednesday, August 31, 2016

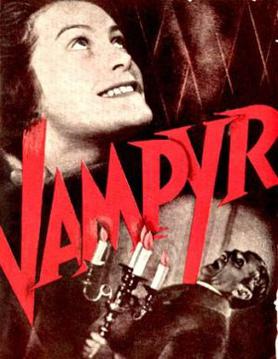

Vampyr (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932)

In the catalog of vampire movies, Vampyr is probably the second scariest after Nosferatu (F.W. Murnau, 1922). Which is odd, because its narrative, based by Dreyer and co-writer Christian Jul on a story be Sheridan Le Fanu, is fractured and almost incoherent and its characterization scattered. But you get the feeling that Dreyer himself really believed in the malevolent creatures he put on film, not surprising since most of Dreyer's films were in one way or another about faith. One story has it that the look of the film came about accidentally: Cinematographer Rudolph Maté shot an early sequence slightly out of focus, and when he apologetically showed it to Dreyer, the director insisted that was exactly how he wanted the film to look. Maté consequently shot many sequences through gauze. Accident also dictated some of the story: Dreyer insisted on location shooting, and in scouting for places to shoot, discovered the flour mill, giving him the idea for the scene in which the doctor meets his rather gruesome end. The lead character, Allen Grey, was played by a non-professional, Nicolas de Gunzburg, under the pseudonym Julian West -- Gunzburg was also the principal financial backer of the film. Most of the rest of the cast were non-professionals as well, and the sense that Vampyr is the result of serendipitous filmmaking has given the film a certain cachet over the years, especially with filmmakers and critics struggling with the restrictions that the corporate bottom line places on their art. To my mind, Vampyr is a collection of fascinating, disturbing images -- the man with the scythe crossing the river, the play of eerie shadows, the unusually successful double exposure that gives us Allen Grey's out-of-body experience, the sequence in which Grey sees himself in a coffin, and so on. But it seems to me to be brilliant parts in search of a satisfying whole.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945)

|

| Celia Johnson in Brief Encounter |

Dr. Alec Harvey: Trevor Howard

Albert Godby: Stanley Holloway

Myrtle Bagot: Joyce Carey

Fred Jesson: Cyril Raymond

Dolly Messiter: Everley Gregg

Mary Norton: Marjorie Mars

Beryl Walters: Margaret Barton

Stephen Lynn: Valentine Dyall

Director: David Lean

Screenplay: Anthony Havelock-Allan, David Lean, Ronald Neame

Based on a play by Noël Coward

Cinematography: Robert Krasker

Art direction: Lawrence P. Williams

Film editing: Jack Harris

Music: Percival Mackey, Muir Mathieson

It had never occurred to me until I started reading essays about Brief Encounter that the movie is a period film: It's set in 1938, which explains why there is no visual evidence of or reference to World War II, which was still going on when it was made. This also helps explain some of the film's jitteriness or reticence about sex. Why, given the facility with which Laura Jesson lies about her relationship with Alec Harvey, don't they just go ahead and have sex? The film is a portrait of prewar middle-class morality, something the war helped break down, especially with the arrival of American troops, proverbially "oversexed and over here," in Britain. When it gained great popularity after the war ended, it was possible to debate whether Brief Encounter was a validation or an indictment of this morality. Is it really healthy for Laura to spend the rest of her life with her pleasantly stuffy husband, dreaming of what might have been? Is it necessary for Alec to uproot his family and emigrate to South Africa just because of sexual frustration? The resolution to their dilemma seems easier to us: We wish Laura and Alec could unbend, the way the working class characters Albert and Myrtle seem to do. (For all her pretense at refinement, it's easy to see that Myrtle has a healthy off-duty sex life.) But then we get glimpses of the social milieu in which Laura and Alec move: He has to contend with the catty nudge-nudge-wink-wink of Stephen Lynn, the friend whose apartment almost becomes a venue for the consummation of their passion; she is surrounded by friends whose only pleasure in life seems to be to talk. There is a real brilliance in the way which Lean, greatly aided by Robert Krasker's noir-expressionist black-and-white cinematography, suggests the entrapment of the lovers in a world they are afraid to break out of. Celia Johnson is magnificent, of course, and it was a stroke of genius to cast Trevor Howard opposite her. For all his kindness and attentiveness, there is something faintly menacing about him, a hint of danger and possibility that can only attract but also subtly frighten a woman whose life consists of helping her husband with the crossword and spending Thursdays in town returning her library book and shopping for an ugly desk tchotchke for his birthday. Everything in this movie is so well judged and efficiently presented that it only makes me regret that Lean turned from such intimate stories and entered on his epic phase.

Monday, August 29, 2016

Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, 2012)

Frances Ha succeeds at what I think it sets out to be: an affectionately amusing look at what an earlier generation called Yuppies -- except that Yuppies seemed to have a much easier time of integrating themselves into adulthood than the Gen Y or Millennial characters in this film. Greta Gerwig, who co-wrote the screenplay with Noah Baumbach, is charmingly awkward as Frances -- whose last name doesn't come from the frequently ironic interjection of "ha ha" in her conversations but from the truncation of her full surname, Halladay, that's revealed at the film's end. Frances is a would-be modern dancer trying to make it in New York even though her talent is, well, marginal. As a result, she's dependent on a collection of friends, including her fellow Vassar alum, Sophie (Mickey Sumner). But when Sophie and others in her life start finding their way in the world, clumsy, agreeable Frances starts to fall behind. If some of this reminds you of the HBO series Girls, and not because both the film and the series feature Adam Driver in a key role, it's not surprising. It's the same set: young middle-class white people in downward mobility when compared with their parents. We meet Frances's parents -- played by Greta Gerwig's own parents, Christine and Gordon Gerwig-- when she goes home to Sacramento for Christmas, a sequence probably designed to remind us why Frances prefers to struggle in New York than to settle for security in a less competitive milieu. Too much of this sort of generational comedy can wear out its welcome, but Frances Ha is so unpretentious -- except perhaps for Baumbach's decision to film it in black and white as an hommage to Woody Allen's Manhattan -- and Gerwig so skillful at creating Frances, that you can't help liking it.

Sunday, August 28, 2016

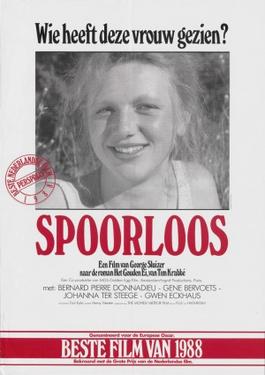

The Vanishing (George Sluizer, 1988)

Nightmarish without being in the least surreal, The Vanishing frightened me more than any horror movie ever has. It's a film about the dangers of curiosity and commitment -- double-edged virtues. A Dutch couple, Rex Hofman (Gene Bervoets) and Saskia Wagter (Johanna ter Steege) are vacationing in France, bickering a bit as couples do. When they run out of gas in the middle of a mountain tunnel, a precarious situation, Rex sets out to get some more, leaving a protesting Saskia behind. When he returns with a can of gas, she's not with the car, but this turns out to be only a temporary "vanishing" -- she's waiting at the side of the road when he emerges from the tunnel. They agree that they both overreacted to the situation -- in fact, the quarrel seems to have made their bond stronger. They reach a rest stop where Rex fills up the tank as well as the emergency canister and Saskia goes to buy drinks -- and never returns. Three years later, Rex is still obsessed with finding Saskia, to the dismay of his new girlfriend, Lieneke (Gwen Eckhaus). Meanwhile, we meet the man responsible for Saskia's disappearance, Raymond Lemorne (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), and watch as Raymond sets a trap into which Rex is lured by his own desire to know what happened to Saskia. (The French title, L'Homme qui voulait savoir -- The Man Who Wanted to Know -- is particularly on point where the crux of the movie is concerned.) The film works by setting up the conventions of the mystery thriller, then subverting them by revealing the identity of the kidnapper and the mechanisms by which he accomplishes his crime. Only the final horror of what Raymond has done with Saskia is withheld until the very end. The performances of Donnadieu and Bervoets go a long way to making the film credible, but it is chiefly the ingenuity of Sluizer's adaptation of the novel by Tim Krabbé that lifts it out of the ordinary. It is a cold-hearted movie that never spares the audience.

Saturday, August 27, 2016

Mission: Impossible -- Rogue Nation (Christopher McQuarrie, 2015)

One of the things that make me think Tom Cruise is smarter than his involvement with Scientology suggests is that lately he has been willing to surround himself in his films with actors who are more appealing than he is. In the case of Rogue Nation, they include Jeremy Renner, Simon Pegg, Ving Rhames, and Rebecca Ferguson. He has also shed the tendency to flash the famous toothy grin on any occasion, though his Ethan Hunt in this film doesn't have much to grin about. As the movie begins, the Impossible Missions Force is about to be disbanded and its members labeled "shoot to kill" by CIA director Alan Hunley (Alec Baldwin). It's a good premise for a thriller, if perhaps an over-familiar one: Make your good guys the target not only of the bad guys but also the other good guys. So off we go on a round of stunts that don't bear summarizing, but McQuarrie's script and direction keep the gee-whiz response pumping for an enjoyable couple of hours. Some critics thought the chief villain, a rogue MI6 agent named Solomon Lane (Sean Harris), wasn't villainous enough, but I have liked Harris's work since I first noticed him as Cesare Borgia's gay henchman Micheletto on the Showtime series The Borgias (2011-2013). He underplays in Rogue Nation, and the decision to dye his hair blond was probably a mistake, but I thought his subtlety was an effective contrast to Cruise's usual tendency to overplay. It has to be said that, at 55, Cruise is just beginning to be a bit implausible in his action sequences, especially the one at the film's beginning that has him leaping onto the wing of a cargo plane and clinging to it as it takes off, Perhaps it's true that he still does his own stunts, but in this golden age of camera tricks and CGI, that seems unnecessary: Audience are going to think it's faked anyway. There may in fact be a nod or two in the movie to Cruise's aging: After the extended underwater swim, Hunt has to be resuscitated, and there are a few moments, played mostly for comic relief by Pegg, when Hunt's disoriented state becomes a matter for concern. A sixth M:I film is evidently in the works. It will be interesting to see whether age plays more of a factor in it.

Friday, August 26, 2016

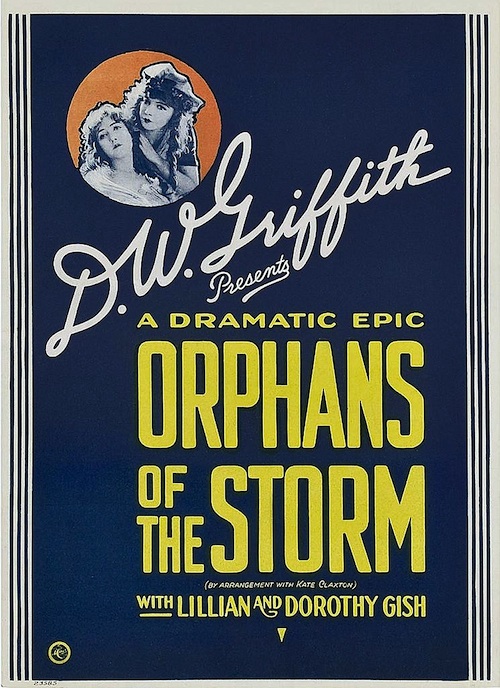

Orphans of the Storm (D.W. Griffith, 1921)

Who knew that one of the chief causes of the French Revolution's Reign of Terror was "Bolshevism"? Or that Danton, who helped send Louis XVI to the guillotine, was "the Abraham Lincoln of France," as one of the title cards for Orphans of the Storm proclaims? D.W. Griffith's gift for pseudo-historical hokum stood him in good stead in making this often preposterous classic, but it worked even better for Lillian and Dorothy Gish, whose performances as the titular orphans are superb. I think Dorothy may give the better performance as Louise, the foundling who is left blind by the "plague" that killed her adoptive parents, but that may be because I've seen Lillian's winsome tricks more often than Dorothy's. Lillian certainly flings herself into the role of Henriette, who became Louise's sister after her parents took in the girl as an infant, and her caretaker after she became blind. The girls go to Paris in search of a cure for Louise's blindness, and there Henriette is abducted by a lecherous aristocrat but saved by the virtuous Chevalier de Vaudrey (a surprisingly handsome young Joseph Schildkraut). Separated from Henriette, Louise falls into the clutches of the conniving Mother Frochard (Lucille La Verne), who puts the blind girl to work begging on the streets. (La Verne sports a monstrous wen and a mustache, reminding us that she was the voice of the wicked queen and the witch in the 1937 Disney Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.) And then comes the Revolution, in which Henriette almost loses her head to the guillotine, thanks to the evil Robespierre (Sidney Herbert), before being rescued by, of all people, Danton (Monte Blue). (An end title informs us that the Reign of Terror ceased when Robespierre was beheaded, but conveniently ignores the similar fate of Danton.) In the end, Henriette and de Vaudrey are to be married, and Louise not only regains her sight but also learns that she was the daughter of the Countess de Linieres (Katherine Emmet) from a previous marriage to a commoner that was suppressed by the countess's family. This delicious stuff, which Griffith's screenplay took from a play by Adolphe d'Ennery and Eugène Cormon along with liberal borrowings from Dumas, Dickens, and Victor Hugo, is kept furiously a-boil by Griffith's superb gift for pacing and cutting. He never lets the action flag, even for the necessary exposition.

Thursday, August 25, 2016

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu, 2007)

|

| Vlad Ivanov, Anamaria Marinca, and Laura Vasiliu in 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days |

Gabita: Laura Vasiliu

Mr. Bebe: Vlad Ivanov

Adi: Alexandru Potocean

Adi's Mother: Luminita Gheorghiu

Adi's Father: Adi Carauleanu

Director: Cristian Mungiu

Screenplay: Cristian Mungiu

Cinematography: Oleg Mutu

A harrowing, brilliant film, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days is set in 1987 Romania, during the final years of the Ceausescu regime. Gabita, a student, wants an abortion, illegal in Romania, so she prevails on her roommate in a university dormitory, Otilia, to help her. But Gabita is so deeply sunk in denial that she's incapable of doing much more than ask for help: It's up to Otilia to do most of the planning and strategy after Gabita has telephoned the abortionist, a Mr. Bebe, to make the initial arrangements. Otilia even borrows money from her boyfriend, Adi, to help Gabita, and when the day arrives, she has been persuaded by Gabita to meet with Bebe and to go to the hotel room Gabita has supposedly reserved. Otilia has to bear the brunt of Bebe's scorn and bullying when he finds he is dealing with an intermediary. The hotel has no record of Gabita's reservation, and Otilia is forced to find a room in another hotel, every time encountering resistance and hostility, plus additional charges, from the hotels. Director Cristian Mungiu, who also wrote the screenplay, finds a tone halfway between Dickens and Kafka in his portrayal of bureaucratic indifference. Moreover, when Gabita finally arrives for the abortion, having characteristically forgotten the plastic sheet she was supposed to bring, we find that her capacity for denial extends to how far advanced her pregnancy really is: She had told Otilia that it has been three months since her period, but Bebe forces her to admit that it has been almost five -- hence the film's title. He demands more money, and when the women are unable to come up with it, he agrees to proceed if they will have sex with him. Mungiu uses long takes, carefully framed without camera movement or cuts, to set up this sordid tale, and the performances by Marinca, Vasilu, and Ivanov are equal to the demands of what amounts almost to filmed theater. After Bebe has performed the procedure and left, while Gabita is waiting to expel the fetus, Otilia leaves for a while, having agreed to attend a birthday dinner for Adi's mother. Once again, Mungiu uses a long take at the dinner table, where the guests, friends of Adi's parents, chatter on inconsequentially as Otilia sits there virtually silent, though obviously anxious about Gabita's plight, as well as feeling guilty about having sex with Bebe. It's to Mungiu's great credit -- not to mention Marinca's -- that he does nothing to communicate this subtext to the scene, other than allow the banality of the dinner table talk to make us focus on Marinca's face and to project our own uneasiness about the situation onto her. Mungiu also contrasts his long, still takes with long tracking shots filmed with a handheld camera as, later, Otilia hurries through the nighttime streets looking for a place to dispose of the fetus. It's undeniably an unpleasant story, but it's also a haunting one, given great resonance by the skillful characterization of the script and its performers and the superb cinematic technique of its director. In the recent BBC poll of film critics to name the best film of the 21st century, 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days came in at No. 15. I might have placed it higher.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

Black Mass (Scott Cooper, 2015)

Having long ago effaced the stigma of being a teen heartthrob on the TV series 21 Jump Street (1987-90), and having earned three Oscar nominations, Johnny Depp no longer has to prove himself as an actor. But his recent career has been marked by disastrous flops -- Alice Through the Looking Glass (James Bobin, 2016), Mortdecai (David Koepp, 2015), The Lone Ranger (Gore Verbinski, 2013) -- and too much reliance on the Pirates of the Caribbean series. Black Mass is a partial redemption for those failings, mostly because Depp becomes the best reason for seeing it. Apart from Depp's cruel and icy portrayal of Boston mobster James "Whitey" Bulger, there's not enough heft and momentum to Scott Cooper's film. It takes a fascinating story of the interrelationships between Bulger's mob, the FBI, and the government of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and reduces it to a routine and often derivative gangster movie. Cooper and screenwriters Mark Mallouk and Jez Butterworth borrow shamelessly from GoodFellas (Martin Scorsese, 1990) in a scene in which Bulger playfully terrorizes a colleague in the same way Joe Pesci's character -- "What do you mean, I'm funny?" -- frightens Ray Liotta's Henry Hill. The film often seems overloaded with good actors -- Joel Edgerton, Benedict Cumberbatch, Kevin Bacon, Peter Sarsgaard, Jesse Plemons, Adam Scott, Julianne Nicholson -- in parts that don't give them enough to do. And while it was filmed in Boston, it misses the opportunity to capture the Boston neighborhood milieu in which Whitey, his politician brother Billy (Cumberbatch), and FBI agent John Connolly (Edgerton) grew up, something that was done to much better effect in films like Mystic River (Clint Eastwood, 2003), Gone Baby Gone (Ben Affleck, 2007), and even Good Will Hunting (Gus Van Sant, 1997). Still, the cold menace projected by Depp's Bulger is haunting, enhanced by the decision to provide the actor with ice-blue contact lenses that pierce through the shadows and give him an air of otherworldly surveillance.

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

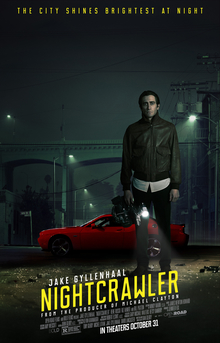

Nightcrawler (Dan Gilroy, 2014)

That an actor as good as Jake Gyllenhaal, still in his 30s, should have to resort to transformative tricks to get a noticeable role is regrettable. Ever since the Brits learned to do American accents that don't sound like they're talking through their noses while chewing gum, young American actors have had it hard. Why should producers take a chance on a Yank when they can hire a Hiddleston or a Cumberbatch or one of the Dominics (Cooper or West)? So you're doing a TV series about a Russian spy pretending to be an American? Naturally you hire Matthew Rhys, a Welshman. Want a fresh face? Check out RADA or that young guy who just got raves playing Hamlet in Bristol. What's an American actor got to do to get a break? If you're Matthew McConaughey trying to avoid getting cast in another rom-com, you lose 47 pounds and win an Oscar. Or if you're Gyllenhaal, you lose all the muscle you built for the turkey Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (Mike Newell, 2010), let your hair go long and greasy, turn yourself into one of the more fascinatingly repellent characters in recent films and get the best reviews you've had since Brokeback Mountain (Ang Lee, 2005). Nightcrawler is a solid drama with a satiric edge, in which Gyllenhaal plays Louis Bloom, a sociopath who roams the streets of Los Angeles at night, listening to a police scanner for reports of shootings, fires, car crashes -- anything that comes under the TV news rubric, "If it bleeds, it leads." He films whatever gore he can worm his way past police lines to witness, then sells it to a local TV news outlet. There are semi-legitimate, better-equipped outfits doing this sort of thing, but they have some scruples. Bloom has none; his amorality is hair-raising. This was the first film as a director for Dan Gilroy, who also wrote the screenplay, and it has a terrific cast supporting Gyllenhaal. Rene Russo plays a TV news producer whose ethical standards are only a shade higher than Bloom's. She makes Faye Dunaway's Diana Christensen in Network (Sidney Lumet, 1976) look almost namby-pamby. Riz Ahmed plays Rick, a homeless kid whom Bloom hires as an assistant and abuses and profoundly exploits. After his turn in HBO's miniseries The Night Of (2016), Ahmed is in danger of getting typed as a wide-eyed patsy. Bill Paxton, one of those actors whose presence always helps make a film better, plays an older and more experienced TV news freelancer who shows Bloom the ropes and winds up getting sabotaged for his efforts.

Links:

Bill Paxton,

Dan Gilroy,

Jake Gyllenhaal,

Nightcrawler,

Rene Russo,

Riz Ahmed

Monday, August 22, 2016

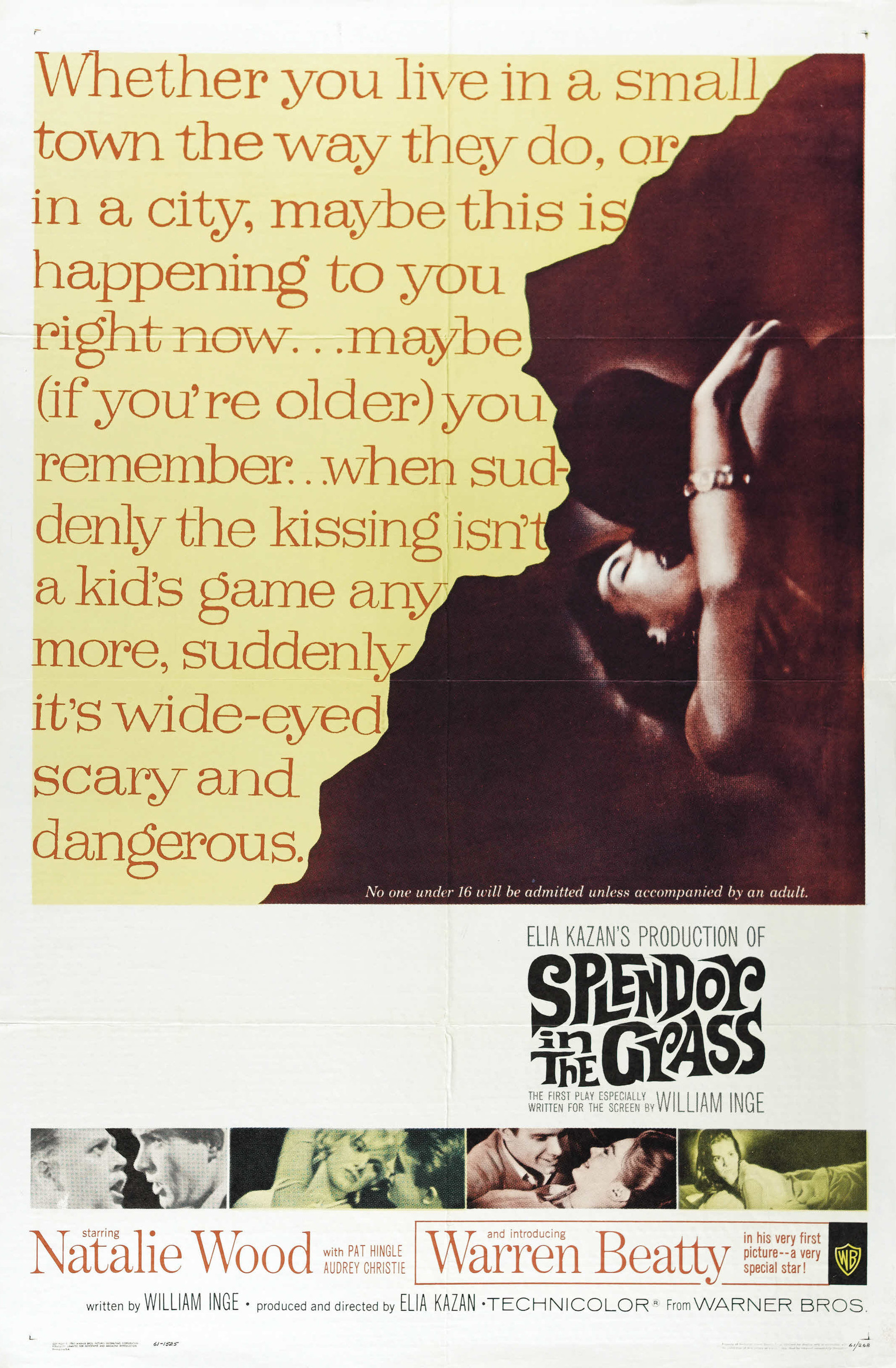

Splendor in the Grass (Elia Kazan, 1961)

This overheated melodrama, released the year after the introduction of the Pill, could almost be a valedictory to the 1950s. Deanie Loomis (Natalie Wood) and Bud Stamper (Warren Beatty) are two hormone-drenched Kansas teenagers in 1928 -- though the attitudes toward sex were still prevalent thirty years later -- unable to find an outlet for the passions they are told they should repress. He is under the sway of a bullying, motormouthed father (Pat Hingle in an over-the-top performance that's alternately frightening and ludicrous), while she has a frigid, convention-ridden mother (Audrey Christie). She goes mad and is sent to a mental hospital. He goes to Yale and flunks out. Such are the consequences of not having sex. The truth is, Splendor in the Grass is not quite as silly as this summary makes it sound. Kazan's direction is, as so often, actor-centered rather than cinematic: The performances of the four actors mentioned give it a lot of energy that at least momentarily overrides any reservations I have about the psychological plausibility of William Inge's screenplay, which won an Oscar. There's also Barbara Loden as Bud's wild flapper sister, and Zohra Lampert as the earthy Italian woman Bud winds up marrying. In the end, the movie becomes almost a documentary of a moment in American filmmaking, when censorship was beginning to lose ground, and things previously unmentionable, like abortion, became at least marginally acceptable. The film itself could almost serve as an indictment of the attitudes that produced the Production Code, which hamstrung American movies from 1934 to 1968. What distinction the movie has other than as a showcase for performances comes from Boris Kaufman's cinematography, Richard Sylbert's production design, and Gene Milford's editing.

Sunday, August 21, 2016

Steamboat Bill Jr. (Charles Reisner, 1928)

Saturday, August 20, 2016

City of God (Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund, 2002)

City of God is an exceptionally involving docudrama that employs non-professional actors to stunning effect. The only experienced professional in the cast was Matheus Nachtergaele, who played the drug dealer known as "Carrot." The rest were mostly recruited from the streets and slums of Rio, and put through several months of training, largely under the supervision of Lund, who also worked with the cast during filming and is billed as "co-director." Lund had become familiar with Rio's slum-dwellers through her work on music videos and documentary films. The shape of the film, including its flashback structure and use of quick cutting and hand-held camera, is largely that of Meirelles, whose most recent work includes coverage of the opening ceremony of the 2016 Olympics in Rio. And that reliance on flashy camerawork and narrative tricks is, I think, the greatest flaw of City of God. It detracts from some of our involvement in the lives of its characters, turning away from documentary-like reality into sheer "movie-making." Nevertheless, the film successfully immerses us in the violent lives of the people of the favelas. It was a significant critical and even commercial hit, earning four Oscar nominations, a rare feat for a foreign-language film. It wasn't submitted by Brazil for the foreign-language Oscar, but instead was nominated for best director, best adapted screenplay (Bráulio Mantovani from the novel by Paulo Lins), cinematography (César Charlone), and film editing (Daniel Rezende). Some controversy arose when only Meirelles was cited in the directing nomination, but the Academy has strict eligibility rules, and Lund's credit of "co-director" was judged to be a disqualifier. Given my reservations about Meirelles's use of the camera, I think maybe Lund deserved the nomination more than he did.

Friday, August 19, 2016

Veronika Voss (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1982)

Thursday, August 18, 2016

High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952)

|

| Gary Cooper and Grace Kelly in High Noon |

Amy Fowler Kane: Grace Kelly

Harvey Pell: Lloyd Bridges

Helen Ramirez: Katy Jurado

Jonas Henderson: Thomas Mitchell

Percy Mettrick: Otto Kruger

Martin Howe: Lon Chaney Jr.

Sam Fuller: Harry Morgan

Frank Miller: Ian MacDonald

Jack Colby: Lee Van Cleef

Mildred Fuller: Eve McVeagh

Dr. Mahin: Morgan Farley

Jim Pierce: Robert J. Wilkie

Ben Miller: Sheb Wooley

Director: Fred Zinnemann

Screenplay: Carl Foreman

Based on a story by John W. Cunningham

Cinematography: Floyd Crosby

Production design: Rudolph Sternad

Film editing: Elmo Williams, Harry Gerstad

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

High Noon, as has often been noted, is a movie of almost classical simplicity, adhering to the unities of place (the town of Hadleyville) and time (virtually, with perhaps only a little fudging, the runtime of the film). There are no flashbacks -- the only expository moment involves a shot of an empty chair -- and no preliminaries or codas: It begins with the wedding of Will Kane and Amy Fowler, and ends with a shot of them riding out of town. It's what makes the movie enduringly satisfying, but also what once seemed to make people want to superadd a layer of significance by interpreting it as a parable about blacklisting. That would have been inevitable anyway, since screenwriter Carl Foreman had been called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and left the country before the film was released. But it strains the tight confines of the film's narrative. Not surprisingly, High Noon took some hits from critics on the right like John Wayne, but it was also stigmatized for a long time as "pretentious." Andrew Sarris called it an "anti-populist anti-Western," but that, too, seems to me to burden the film with too much message. (Anyway, aren't Westerns, with their emphasis on wandering loners, essentially "anti-populist"?) Sixty-five years later, it's possible to view High Noon as nothing more than a neat and tidy narrative about simple heroism, which is not at all "anti-Western," a phrase that suggests far more psychological complexity than the movie possesses. Will Kane is still the good guy and Frank Miller and his gang are black-hearted baddies. If you want moral complexity, go watch The Searchers (John Ford, 1956) or The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969). It's true that High Noon was overpraised at the time, winning four Oscars -- for Cooper, film editors Elmo Williams and Harry Gerstad, composer Dimitri Tiomkin for the score and, with lyricist Ned Washington, the song "High Noon (Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin')" -- and nominations for best picture, director, and screenplay. But that the Academy should even have acknowledged the virtues of a Western, a genre it typically looked down upon, is significant -- even though it reverted to its usual indifference to the genre a few years later, when it entirely ignored The Searchers.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

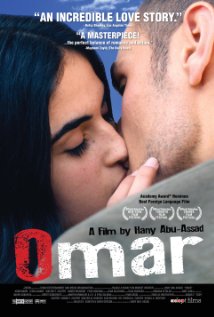

Omar (Hany Abu-Assad, 2013)

Omar is an involving thriller that earned an Oscar nomination for best foreign language film, and currently has a 90 percent "fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes. But a few critics think it goes too far in depicting its Palestinian characters as good guys and the Israelis as villains -- the word "agitprop" has been used. Which goes to show once again that art and politics are uneasy, if necessary, companions. The film was made with Palestinian money, and the country submitting it for the Oscar was Palestine (whose designation as a country itself stirs controversy), but it was filmed in the Israeli city of Nazareth as well as in the West Bank city of Nablus. Omar (Adam Bakri) is a young man who, after being tormented by Israeli soldiers, joins with his friends Tarek (Eyad Hourani) and Amjad (Samer Bisharat) in retaliation. They sneak up on an Israeli encampment and Amjad (though reluctantly) shoots one of the soldiers. When Omar is captured and tortured, he is tricked by an Israeli officer, Rami (Waleed Zuaiter), posing as a Palestinian, into saying "I will never confess," which the military courts recognize as tantamount to a confession. But Rami persuades Omar to take a deal: He can go free if he will work to lead them to Tarek, whom they identify as the leader of the group. What follows is a complex story of betrayal and retribution, complicated by Omar's love for Tarek's sister Nadia (Leem Lubany). Omar stays just shy of sinking into pure melodrama, thanks to director Abu-Assad's screenplay, his well-handled action sequences of the pursuit of Omar through the narrow streets and across the rooftops of Nazareth, and some effective performances by attractive young actors like Bakri and Lubany. The glimpses of a culture too often seen through the lens of geopolitics also strengthen the film. The film may be politically biased, but it's also a tale of the strong vs. the weak, which may be why so many of us can ignore the complexities of the actuality underlying it.

Tuesday, August 16, 2016

Broken Blossoms (D.W. Griffith, 1919)

The raw pathos of Broken Blossoms has probably never been equaled on film, thanks to three extraordinary performers. Lillian Gish is a known quantity, of course, but it's startling to see Donald Crisp as one of the most odious villains in film history. Crisp, whose film-acting career spanned more than fifty years, from the earliest silent shorts through his final performance in Spencer's Mountain (Delmer Daves, 1963), is best known today for fatherly and grandfatherly roles in How Green Was My Valley (John Ford, 1941), Lassie Come Home (Fred M. Wilcox, 1943), and National Velvet (Clarence Brown, 1944), but his performance as Battling Burrows is simply terrifying. As the cockney fighter, he displays a macho strut that might have influenced James Cagney. Richard Barthelmess is no less impressive as Cheng Huan, known in the film mostly as The Yellow Man. We have to make allowances for the stereotyping and the "yellowface" performance today, but Barthelmess (and Griffith) deserve some credit for ennobling the character, running counter to the widespread anti-Asian sentiments and fear of miscegenation in the era. Barthelmess, who became a matinee idol, makes The Yellow Man simultaneously creepy and sympathetic. And then there's Gish, who as usual throws herself (almost literally) into the role of the waif, Lucy. It's an astonishing performance that virtually defined film acting for at least the next decade, until sound came in and actors could rely on something other than their faces and bodies to communicate. True, some of her gestures lent themselves to parody, as when Buster Keaton steals Lucy's trick of pushing up the corners of her mouth to force a smile in Go West (1925), but parody is often the sincerest form of flattery.

Monday, August 15, 2016

A Most Violent Year (J.C. Chandor, 2014)

|

| Jessica Chastain and Oscar Isaac in A Most Violent Year |

Anna Morales: Jessica Chastain

Julian: Elyes Gabel

Andrew Walsh: Albert Brooks

D.A. Lawrence: David Oyelowo

Peter Forente: Alessandro Nivola

Director: J.C. Chandor

Screenplay: J.C. Chandor

Cinematography: Robert Levi, Bradford Young

In a movie that might have been called "Do the Most Right Thing," Oscar Isaac plays yet another ethically challenged protagonist. Abel Morales is not as cranky as Llewyn Davis or as politically savvy as Nick Wasicsko, the beleaguered Yonkers mayor of the 2015 HBO series Show Me a Hero, but he's another little guy who deserves better than the forces opposed to him will allow. He's no moral paragon: He couldn't have built a successful heating oil company in New York City without bending a few of the rules -- and without the help of his less-scrupulous wife, Anna. It's 1981, and Morales is on the brink of a big deal, purchasing property on the East River that will enable him to eliminate some of the middlemen in the business. But then everything starts going awry: His trucks are being hijacked and the district attorney has decided to make him a target in his exposé of corrupt practices in the heating oil business. It's a gritty urban tale, the kind that the movies haven't seen much of lately, demanding an audience that doesn't ask for a lot of glamour and knows how to wait patiently for things to unfold. As director and screenwriter, J.C. Chandor resists the temptation to reveal too much too swiftly, building a quiet tension as we begin to bring the story into focus. He also handles action well, as the title suggests, although much of the violence is latent. Best of all, he showcases some fine performances, not only from Isaac and Chastain and Oyelowo, but also from Albert Brooks as Morales's attorney, Elyes Gabel as one of the victimized truck drivers, and Alessandro Nivola as one of Morales's mobbed-up competitors. There are moments when the script's depiction of Morales's determination to go as straight as possible seems a little too much like forcing him into the good-guy role, and the climax is too melodramatic, but on the whole it's a solid movie.

Sunday, August 14, 2016

The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)

Preston Sturges, who was a screenwriter before he became a hyphenated writer-director, has a reputation for verbal wit. It's very much in evidence in The Lady Eve, with lines like "I need him like the ax needs the turkey." But what distinguishes Sturges from writers who just happen to fall into directing is his gift for pacing the dialogue, for knowing when to cut. What makes the first stateroom scene between Jean (Barbara Stanwyck) and Charles (Henry Fonda) so sexy is that much of it is a single take, relying on the actors' superb timing -- and perhaps on some splendid coaching from Sturges. But he also has a gift for sight gags like Mr. Pike (Eugene Pallette) clanging dish covers like cymbals to demand his breakfast. And his physical comedy is brilliantly timed, particularly in the repeated pratfalls and faceplants that Fonda undergoes when confronted with a Lady Eve who looks so much like Jean. Fonda is a near perfect foil for gags like those, his character's dazzled innocence reinforced by the actor's undeniable good looks. There's hardly any other star of the time who would make Charles Pike quite so credible: Cary Grant, for example, would have turned the pratfalls into acrobatic moves. The other major thing that Sturges had going for him is a gallery of character actors, the likes of which we will unfortunately never see again: Pallette, Charles Coburn, William Demarest (who made exasperation eloquent), Eric Blore, Melville Cooper, and numerous well-chosen bit players.

Saturday, August 13, 2016

Shaun the Sheep Movie (Mark Burton and Richard Starzak, 2015)

The look of Aardman Animations' stop-motion characters hasn't changed much in the years since the first Wallace and Gromit short in 1990, though the humanoid characters have become more diverse. We now see people of color, including a Muslim woman wearing a hijab, on the street. And the basic slapstick humor hasn't changed, either. It still has that essentially British overtone, even in Shaun the Sheep Movie, which has no intelligible dialogue. I doubt, for example, that Pixar, even though its films are perceptibly influenced by Aardman, would venture into the kind of fart jokes and the gags based on the anus of a pantomime horse that are on display in this movie. And all of that is to the good. For what the Aardman films do so well -- especially the ones by Nick Park, who created Shaun and his colleagues, and is listed as executive producer on this film -- is revive the fine art of Sennett and Chaplin and Keaton and Arbuckle, the masters of silent slapstick comedy. Aardman has the advantage that its actors are clay and not flesh, so they can undergo assaults that would obliterate even so resilient an actor as Buster Keaton, but it succeeds in making its characters believable by putting limits on the mayhem. We know that the actors are putty in the hands of the animators, and yet somehow we wince at their peril when they're trapped by the villain on the edge of what a sign describes as "Convenient Quarry." (One of the delights of the movie, which makes you want to watch it again, are the blink-and-you-miss-it gags on the fringe of the action, like that sign.) Shaun the Sheep Movie was nominated for the best animated feature Oscar, but lost to Pixar's brilliant Inside Out. These are grand times indeed for animation.

Friday, August 12, 2016

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

The technology used in it may have dated, but The Conversation seems more relevant than ever. When it was made, the film was very much of the moment: the Watergate moment, which was long before email and cell phones. Julian Assange was only 3 years old. What has kept Coppola's film alive is that he had the good sense to make it a thriller about the consequences of knowledge. The real victim of Harry Caul's snooping is Harry Caul himself, the professional whose delight in what he can do with his microphones and tape recorders begins to fade when he realizes that technology is not an end in itself. It is one of the great Gene Hackman performances from a career crowded with great and varied performances. Ironically, the film that The Conversation most reminds me of today is The Lives of Others, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's 2006 film about eavesdropping by the Stasi in East Germany, which was praised by conservatives like John Podhoretz and William F. Buckley and called one of "the best conservative movies of the last 25 years" by the National Review for its account of surveillance by a communist regime. But Harry Caul is a devout Roman Catholic and an entrepreneur, making his living with the same technology and the same techniques as the Stasi spy of Donnersmarck's film -- capitalism alive and well. The film is something of a technological marvel itself: The great sound designer and editor Walter Murch was responsible for completing it after Coppola was called away to work on The Godfather, Part II, and the texture of the film depends heavily on the way Murch was able to manipulate the complexities of sound that form the key scenes, especially the opening sequence in which Caul is conducting his surveillance of a couple in San Francisco's crowded and busy Union Square. It's true that Murch cheats a little at the ending, when the line, "He'd kill us if he got the chance," is repeated. Caul had extracted it from a distorted recording, and took it to mean that the couple (Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) were in danger from the man who commissioned the surveillance. But at the end, the line is heard again as "He'd kill us if he got the chance," an emphasis that reveals to Caul, too late, that they are the killers, not the victims. It's unfortunate that so much depends on the discrepancy between the way we originally hear the line and the later delivery of it. Still, I don't think it's a fatal flaw in a still vital and gripping movie.

Thursday, August 11, 2016

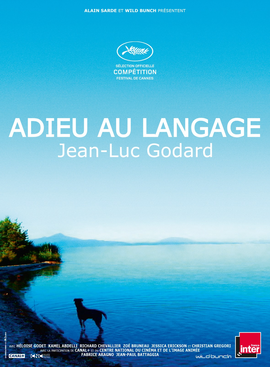

Goodbye to Language (Jean-Luc Godard, 2014)

Is Goodbye to Language the autumnal masterwork of a genius filmmaker? Or is it just an exercise in playing with old techniques -- montage, jump cuts, oblique and fragmented narrative -- in a new (at least to Godard) medium -- 3D? Not having seen the film in 3D, I'm not perhaps fully qualified to comment, but I have to say that it didn't open any new insights for me into the potential of film or the Godard oeuvre as a whole. That in the film Godard makes the wanderings of a dog more coherent and interesting than the conflicts of his human characters is telling: He is obviously more emotionally invested in the dog, played by his own pet, Roxy Miéville, than in the people, whose story can only be pieced together from the fragments of what they do and say to each other. Language, as the title suggests, is subordinate to direct sensation, in which the dog has an advantage over the incessantly chattering and analyzing humans. Godard suggests this through a barrage of quotations from philosophers and novelists, which keep tantalizing us away from simply absorbing the images that he also floods the film with -- the cinematographer, responsible for many of the novel 3D effects, is Fabrice Aragno. Even without 3D, Goodbye to Language is often quite beautiful, with its saturated colors, but I'm not convinced that it adds up to anything novel or revelatory.

Wednesday, August 10, 2016

David Copperfield (George Cukor, 1935)

As long as there are novels and movies, there will be people trying to turn novels into movies. Which is a task usually doomed to some degree of failure, given that the two art forms have significantly different aims and techniques. Novels are interior: They reveal what people think and feel. Movies are exterior: Thoughts and feelings have to be depicted, not reported. Novels breed reflection; movies breed reaction. Novel-based movies usually succeed only when the genius of the filmmakers exceeds that of the novelist, as in the case, for example, of Alfred Hitchcock's transformation (1960) of Robert Bloch's Psycho, or Francis Ford Coppola's extrapolation (1972) from Mario Puzo's The Godfather. We mostly settle for, at best, a satisfying skim along the surface of the novel, which is what we get in Cukor's version of Dickens's novel. I'm not claiming, of course, that Cukor or the film's producer, David O. Selznick, was a greater genius than Dickens, but together -- and with the help of Hugh Walpole, who adapted the book, and Howard Estabrook, the credited screenwriter -- they produced something of a parallel masterpiece. They did so by sticking to the visuals of the novel, not just Dickens's descriptions but also the illustrations for the original edition by "Phiz," Hablot Knight Brown. The result is that it's hard to read the novel today without seeing and hearing W.C. Fields as Micawber, Edna May Oliver as Betsey Trotwood, or Roland Young as Uriah Heep. The weaknesses of the film are also the weaknesses of the book: women like David's mother (Elizabeth Allan) and Agnes Wickfield (Madge Evans) are pallid and angelic, and David himself becomes less interesting as he grows older, or in terms of the movie, as he ceases to be the engaging Freddie Bartholomew and becomes instead the vapid Frank Lawton. But as compensation we have the full employment of MGM's set design and costume departments, along with a tremendous storm at sea -- the special effects are credited to Slavko Vorkapich.

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

Room (Lenny Abrahamson, 2015)

|

| Jacob Tremblay and Brie Larson in Room |

Monday, August 8, 2016

The Wild Bunch (Sam Peckinpah, 1969)

"It ain't like it used to be, but it'll do." The last line of The Wild Bunch, spoken by Edmond O'Brien's Sykes, sums up the film's prevailing sense that something has been lost, namely, a kind of innocence. Myths of lost innocence are as old as the Garden of Eden, and the Western as genre has always played on that note of something unspoiled being swept away with the frontier, though seldom with such eloquent violence as Peckinpah's film. Notice, for example, how many children appear in the movie, often in harm's way, as if their innocence was under attack. The film begins with a group of children at play, but what they're playing with is a scorpion being tormented by a nest of ants. Finally, after the grownups have had a major shootout, endangering other innocents, including a mostly female prohibitionist group, the children set fire to their little game, creating a neat image of hell that sets the tone for the rest of the film. Children, Peckinpah seems to be saying, have only a veneer of innocence, one that's easily removed. So we have children not only under fire but also sometimes doing the firing. They treat the torture of Angel (Jaime Sánchez) as a game, running after the automobile that is dragging him around the village. Not many films use violence for such integral purpose, and not many films have been so wrong-headedly criticized for being violent. Before it was re-released in 1995, Warner Bros. submitted the newly extended cut of the film to the ratings board, which tried to have it labeled NC-17 -- usually a kiss of death because many newspapers refused to advertise movies with that rating. Ordinarily, I'd applaud any effort by the board to treat violence with the same strictness that it treats sex and language, but this decision only emphasizes the shallow, formulaic nature of the board's rulings. An appeal resulted in overturning the rating, so the film was released with an R. Film violence has escalated so much in recent years that if it weren't for the bare breasts in some scenes, The Wild Bunch might get a PG-13 today. I also think the real reason for the emphasis on violence in commentaries on The Wild Bunch is a puritanical one: The movie is too much fun for some people to take seriously. It has superbly staged action scenes, like the hijacking of the train and the demolition of the bridge. And it has entertaining, career-highlight performances by William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Warren Oates, Ben Johnson, and Robert Ryan. The cinematography by Lucien Ballard and the Oscar-nominated score by Jerry Fielding are exceptional. And it's "just a Western," so no high-toned viewers need take it seriously, though surprisingly the Academy did nominate Peckinpah, Walon Green, and Roy N. Sickner for the writing Oscar. They lost to William Goldman for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a movie that feels flimsier as every year goes by.

Sunday, August 7, 2016

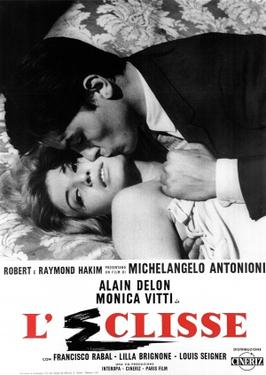

L'Eclisse (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1962)

I'm still an admirer of Pauline Kael's film criticism, but it has dated. She did a great service in her heyday, the 1970s, by cutting through the thickets of snobbery to advance the careers of American filmmakers like Robert Altman and Sam Peckinpah. But that often meant attacking "art house" filmmakers like Antonioni and Alain Resnais, poking at their supposed intellectual pretensions. Although I was never a "Paulette," my career as a professional film critic having been a matter of a few months reviewing for a city magazine, I think I qualified at least as a Kaelite: one who took her point of view as definitive. For a long time, I scoffed at films by Antonioni, Resnais, and others like Ingmar Bergman who got glowing notices from the high-toned critics but zingers from Kael. The bad thing is that I missed, or misinterpreted, a lot of great movies; the good thing is that I can spend my old age rediscovering them. And L'Eclisse is a great movie. One that, to be sure, Kael could dismiss as "cold" and mock for its director's use of Monica Vitti as a vehicle for his views on "alienation." I will grant that Vitti's limited expressive range can be something of a hindrance to full appreciation of the film. But it would have been a very different movie if a more vivid actress like Jeanne Moreau or Anna Karina or even Delphine Seyrig had played the role of Vittoria. Vitti's marmoreal beauty is very much the point of the film: She is irresistibly attractive and at the same time frozen. Alain Delon's lively Piero begins to become blocked and awkward in his attempts to rouse her passion. In the opening scene, in which Vittoria tells Riccardo (Francisco Rabal) that she's leaving him, the two behave in an almost robotic, mechanical way, unable to release anything that feels like a natural human emotion at the event. We see later that Vittoria is able to let herself go, but only when sex is not in the offing and when she is playing someone other than herself: i.e., when she blacks up and pretends to be an African dancer. But Marta (Mirella Ricciardi) puts a stop to this by saying "That's enough. Let's stop playing Negroes." Marta, a colonial racist who calls black people "monkeys," evokes the repressive side of European civilization, but L'Eclisse transcends any pat statements about "alienation" through its director's artistry, through the way in which Antonio plays on contrasts throughout. We move from the slow, paralyzed male-female relationships to the frenzy of the stock exchange scenes, from Vittoria's rejection of Piero's advances to scenes in which they are being silly and having fun. Nothing is stable in the film, no emotion or relationship is permanent. And the concluding montage of life going on around the construction site where Vittoria and Piero have seemingly failed to make their appointment is one of the most eloquent wordless sequences imaginable."Some like it cold. Michelangelo Antonioni on alienation, this time with Alain Delon and, of course, Monica Vitti. Even she looks as if she has given up in this one."--Pauline Kael, 5001 Nights at the Movies

Saturday, August 6, 2016

The Searchers (John Ford, 1956)

Every time I watch The Searchers I find myself asking, is this really a great movie? It took seventh place on the 2012 Sight and Sound poll that ranks the best movies of all time. For my part, I think Red River (Howard Hawks, 1948) a richer, more satisfying film -- and, incidentally, the one that taught John Ford that John Wayne could act. And among Ford films, I prefer Fort Apache (1948) and even Stagecoach (1939). The Searchers is riddled with too many stereotypes, from John Qualen's "by Yiminy" Swede to the "señorita" who clatters her castanets while Martin Pawley (Jeffery Hunter) is trying to eat his frijoles, but most egregiously the "squaw" (Beulah Archuletta) whom Martin accidentally buys as a wife. (Notably, the two most prominent Native American roles in the film are played by Archuletta, whose 31 IMDb credits are mostly as "Indian squaw," and Henry Brandon, who was born in Germany, as Scar.) There is too much not very funny horseplay in the film, a lot of it having to do with the humiliation of Martin by Ethan Edwards (Wayne). Martin also takes a drubbing from the woman who loves him, Laurie Jorgenson (Vera Miles). It's almost as if, dare I suggest, the 62-year-old Ford took a sadistic delight in beating up on handsome young men, since he does it again in the film with Patrick Wayne's callow young Lt. Greenhill. (Do I really need to explain the significance of the way Ward Bond's Reverend keeps belittling the lieutenant's sword as a "knife"?) And although Monument Valley, especially as photographed by Winton C. Hoch, is a spectacular setting, by the time of The Searchers Ford had used it so often as a stand-in for the entire American West that he has reduced it to the status of a prop. Yet by the time Ethan Edwards stands framed in the doorway, one of the great concluding images of American films, I'm resigned to the fact of the film's greatness. It consists in what the auteur critics most admired in directors: It is a very personal film, imbued in every frame with Ford's sensibility, rough-edged and wrong-headed as it may be. And Wayne's enigmatic Ethan Edwards is one of the great characters of American movies -- not to mention one of the great performances. We never find out what motivates his obsessive search for Debbie (Natalie Wood), leading some to speculate unnecessarily that she's really his daughter by Martha Edwards (Dorothy Jordan), his brother's wife. And his radical about-face when he finally lifts Debbie, a reprise of what he did with the child Debbie (Lana Wood) at the start of the film, and takes her home, after threatening to kill her throughout the film, is as enigmatic as the rest of his behavior. But it's a human enigma, and that's what matters. Ford's strength as a director always lay in his heart, not his head. In the end, The Searchers really tells us as much about John Ford as it does Ethan Edwards.

Friday, August 5, 2016

The Conformist (Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

Of all the hyphenated Jeans, Jean-Louis Trintignant seems to me the most interesting. He doesn't have the lawless sex appeal of Jean-Paul Belmondo, and he didn't grow up on screen in Truffaut films like Jean-Pierre Léaud, but his career has been marked by exceptional performances of characters under great internal pressure. From the young husband cuckolded by Brigitte Bardot in And God Created Woman (Roger Vadim, 1956) and the mousy law student in whom Vittorio Gassman tries to instill some joie de vivre in Il Sorpasso (Dino Risi, 1962), through the dogged but eventually frustrated investigator in Z (Costa-Gavras, 1969) and the Catholic intellectual who spends a chaste night with a beautiful woman in My Night at Maud's (Eric Rohmer, 1969), to the guilt-ridden retired judge in Three Colors: Red (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1994) and the duty-bound caregiver to an aged wife in Amour (Michael Haneke, 2012), Trintignant has compiled more than 60 years of great performances. His most popular film, A Man and a Woman (Claude Lelouch, 1966), is probably his least characteristic role: a romantic lead as a race-car driver, opposite Anouk Aimée. His role in The Conformist, one of his best performances, is more typical: the severely repressed Fascist spy, Marcello Clerici, who is sent to assassinate his old anti-Fascist professor (Enzo Tarascio). Marcello's desire to be "normal" is rooted in his consciousness of having been born to wealth but to parents who have abused it to the point of decadence, with the result that he becomes a Fascist and marries a beautiful but vulgar bourgeoise (Stefania Sandrelli). Bertolucci's screenplay places a heavier emphasis on Marcello's repression of homosexual desire than does its source, a novel by Alberto Moravia. In both novel and film, the young Marcello is nearly raped by the chauffeur, Lino (Pierre Clémenti), whom Marcello shoots and then flees. But in the film, Lino survives to be discovered by Marcello years later on the streets the night of Mussolini's fall. Marcello, whose conformity does an about-face, sics the mob on Lino by pointing him out as a Fascist, and in the last scene we see him in the company of a young male prostitute. This equating of gayness with corruption is offensive and trite, but very much of its era. Even the sumptuous production -- cinematography by Vittorio Storaro, design by Ferdinando Scarfiotti, music by Georges Delerue -- doesn't overwhelm the presence of Trintignant's intensely repressed Marcello, with his stiff, abrupt movements and his tightly controlled stance and walk. If The Conformist is a great film, much of its greatness comes from Trintignant's performance.

Thursday, August 4, 2016

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

|

| Kirk Douglas and Adolphe Menjou in Paths of Glory |

Cpl. Philippe Paris: Ralph Meeker

Gen. George Broulard: Adolphe Menjou

Gen. Paul Mireau: George Macready

Lt. Roget: Wayne Morris

Maj. Saint-Auban: Richard Anderson

German Singer: Christiane Kubrick

Cafe Owner: Jerry Hausner

Chief Judge: Peter Capell

Father Dupree: Emile Meyer

Sgt. Boulanger: Bert Freed

Pvt. Lejeune: Kem Dibbs

Pvt. Maurice Ferol: Timothy Carey

Shell-Shocked Soldier: Fred Bell

Capt. Rousseau: John Stein

Capt. Nichols: Harold Benedict

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Calder Willingham, Jim Thompson

Based on a novel by Humphrey Cobb

Cinematography: Georg Krause

Art direction: Ludwig Reiber

Film editing: Eva Kroll

Music: Gerald Fried

Kirk Douglas gives an uncharacteristically restrained performance in Paths of Glory, but the real star of the film is director Stanley Kubrick, who gives the big battle scene a kind of choreographed intensity. Kubrick had begun his career as a photographer for Look magazine and had been his own cinematographer on his early short films and his features Fear and Desire (1953) and Killer's Kiss (1955). Although the cinematographer for Paths of Glory is Georg Krause, it's easy to sense Kubrick's direction as he anticipates the battle scene's relentless motion with long takes and tracking shots in the earlier parts of the film, when the camera observes Gen. Broulard persuading Gen. Mireau to commit his troops to the suicidal assault on the German-held "Ant Hill." We follow Broulard and Mireau as they move through the opulent French headquarters (actually the Schleissheim Palace in Bavaria), circling each other as Broulard plays on Mireau's ambition and overcomes his resistance, Then we move to the trenches, a sharp contrast in setting from the palace, where the camera tracks Mireau as he walks down the long narrow ditch, greeting soldiers in a stiff, formulaic way and berating one who is stupefied by shell shock as a coward. The tracking shot of Mireau's tour of the trenches is then repeated with Col. Dax in the moments before the suicidal assault on the Ant Hill, although this time the air is full of smoke and debris from the shelling. Then Dax goes over the top, blowing a shrill whistle to lead his troops, and we have long lateral tracks punctuated by explosions and falling men. Film editor Eva Kroll's work adds to the power of the sequence. If the acting and the screenplay (by Kubrick, Calder Willingham, and Jim Thompson) were as convincing as the camerawork, Paths of Glory might qualify as the masterpiece that some think it is. Douglas, Menjou, and Macready are fine, and Wayne Morris and Ralph Meeker have a good scene together as members of a scouting party on the night before the battle, in which the drunkenness and cowardice of Morris's character has fatal consequences. But the scenes in which the three soldiers court-martialed for the failure of the assault face the prospect of the firing squad go on much too long, and are marred by the overacting of Timothy Carey as the "socially undesirable" Private Ferol and the miscasting of Emile Meyer, who usually played heavies, as Father Dupree. (Carey was actually fired from the film, and a double was used for some scenes.) And the film ends with a mawkish and unconvincing scene in which a captured German girl (the director's wife-to-be, Christiane Kubrick) reduces the French troops to tears with a folk song. Paths of Glory has to be described as a flawed classic.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Ex Machina (Alex Garland, 2015)

Screenwriter Alex Garland's debut as director has a lot going for it: a tightly provocative and suspenseful Oscar-nominated screenplay (also by Garland), a superb trio of stars, and special effects that don't overwhelm the story. The effects won Oscars for Andrew Whitehurst, Paul Norris, Mark Williams Ardington, and Sara Bennett, overcoming competitors with far more flash and dazzle: Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller), The Martian (Ridley Scott), The Revenant (Alejandro González Iñárritu), and Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams). For once, special effects were kept on the human scale, largely to present Ava (Alicia Vikander) as the ambiguous cross between human being and robot on which the screenplay's exploration of the ethics of artificial intelligence depends. Ava (whose name is a variant spelling of "Eve") is the creation of Nathan (Oscar Isaac), a superwealthy tech genius who made his fortune with an Internet search engine not named Google, which he uses as the software for his experiment. He lures a young coder, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), to his isolated retreat on the pretext that he wants Caleb to apply the Turing test on Ava. Nathan's unstated aims are far more extensive, and Caleb sees through them quickly. But neither of them is quite as quick on the uptake as Ava. Gleeson is convincingly geeky as Caleb, and Isaac, in yet another performance that establishes him as one of our most chameleonic actors, evokes the self-absorption and questionable ethics of any number of tech billionaires. But it's Vikander who steals the honors with Ava's sly mixture of naïveté and nascent cunning. The only thing I can fault Ex Machina for is a conventional sci-fi ending that feels out of keeping with the intelligent questioning of the middle part of the script and seems too much like a setup for a sequel.

Tuesday, August 2, 2016

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

|

| Pam Grier and Robert Forster in Jackie Brown |

Monday, August 1, 2016

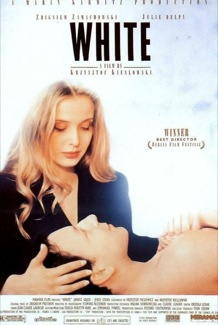

Three Colors (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1993, 1994)

I skipped a couple of days' postings because I wanted to watch all three films in Kieslowski's trilogy before writing about them. The trilogy was once a big deal, earning Kieslowski multiple awards, but I think its reputation has faded a bit. It's remarkably clever in its play on the three colors of the French flag, and its visual use of each one in the corresponding film, and in the way bits of action are used to link the three films, but I think the cleverness sometimes results in heavy-handedness.

Blue (1993)

The extraordinary cinematography of Slawomir Idziak and the performance by Juliette Binoche carry this first film in the trilogy, which takes liberté, the color signified by blue in the French tricolor, as its theme. Binoche plays Julie, who survives a car crash that kills her husband and daughter. Finding that she is unable to swallow the pills she obtains to commit suicide, she determines to live a completely detached life, doing nothing. Her husband, Patrice, was a famous composer, and Julie, also a composer, refuses to aid Olivier (Benoît Régent), her husband's sometime collaborator, in completing the concerto Patrice had been composing in celebration of the formation of the European Union. After sleeping with Olivier, Julie puts the estate she and her husband owned up for sale and tries to go into hiding, renting a small flat in Paris. But however much she tries to disengage herself from the world around her, Julie keeps being drawn back in. She refuses to sign a neighbor's petition to evict Lucille, a dancer in a strip club, thereby earning Lucille's gratitude. She is sought out by a boy who witnessed the fatal accident and wants to return a gold cross he found at the site and to tell her Patrice's last words -- the punch line to a joke he was telling when he lost control of the car. And she discovers that her husband had a mistress, who is carrying the child he didn't know he had conceived with her. All of this leads Julie to the realization that the liberty she had sought is illusory, that it can't be found in detachment but, to put it in terms of the tricolor, in conjunction with equality and fraternity -- treating Lucille as a equal, for example, and collaborating with Olivier to complete Patrice's concerto, which takes as text for its choral section the verses about love in 1 Corinthians. Visually beautiful with striking use of the titular color throughout, Blue has a romantic glossiness that takes away from the grit and urgency that it might have benefited from.

White (1994)

The middle film of the trilogy is a dark comedy about an exiled Polish hairdresser, Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), whose French wife, Dominique (Julie Delpy), divorces him because of his impotence. Still desperately in love with Dominique, Karol finds himself homeless, playing tunes on a comb and tissue paper to earn small change in the Métro. Another Pole hears Karol playing a Polish song and strikes up an acquaintance, eventually helping Karol smuggle himself back to Poland in a large suitcase, which is stolen before Karol can emerge from it. After being dumped in a landfill, Karol makes his way home to his brother's beauty parlor, and begins a long process of rehabilitation, in which he makes a fortune, and devises an elaborate plot that involves faking his own death, with which he eventually gets even with Dominique, though the revenge is bittersweet. The screenplay, written by Kieslowski with his usual collaborator, Krzysztof Piesewicz, is ingeniously put together, though the theme of égalité is not quite so central to White as the corresponding color themes are to Blue and Red. Zamachowski is impressive in his journey from victim to victor, but Delpy's role feels somewhat undeveloped. What could have attracted her to this schlub in the first place? As usual, there are some ingenious links between White and the other two films: Juliette Binoche's Julie can be glimpsed entering the courtroom where Karol and Dominique's divorce hearing is taking place, just as in Blue, we caught a glimpse of Delpy and Zamachowski from Julie's point of view in the same setting.

Red (1994)

Not only the last film in the trilogy, Red was also Kieslowski's final film before his death. He had announced his retirement after the release of the film, and died of complications from open-heart surgery in 1996. The film drew three Oscar nominations, for director, screenplay (Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesewicz), and cinematography (Piotr Sobocinski). It deserved one for Jean-Louis Trintignant's performance as Joseph Kern, a retired judge who spends his time electronically eavesdropping on his neighbors' phone calls. Irène Jacob plays Valentine, a model who encounters Kern when she accidentally hits his dog with her car. The two strike up an unusual friendship as the beautiful young woman draws the misanthropic judge out of his self-imposed exile, ironically by awakening his conscience and causing him to turn himself in to the authorities who convict him of invasion of privacy. In the tricolor scheme, red stands fraternité, and the film delivers on the theme with Kern's emerging empathy. Again, the film links with its predecessors, both of which included scenes in which an elderly person, bent with age, struggles to force a plastic bottle into an aperture in a recycling bin. In Blue, Julie ignored and perhaps didn't even see the person's difficulty; Karol in Red notices but does nothing to help. Only Valentine sees and goes to the person's aid. But I find the ending of Red a little forced, in which the survivors of a disaster at see include not only Valentine, but also Julie and Olivier from Blue, and Karol and Dominique, who have somehow reunited despite the ending of White.

Blue (1993)

The extraordinary cinematography of Slawomir Idziak and the performance by Juliette Binoche carry this first film in the trilogy, which takes liberté, the color signified by blue in the French tricolor, as its theme. Binoche plays Julie, who survives a car crash that kills her husband and daughter. Finding that she is unable to swallow the pills she obtains to commit suicide, she determines to live a completely detached life, doing nothing. Her husband, Patrice, was a famous composer, and Julie, also a composer, refuses to aid Olivier (Benoît Régent), her husband's sometime collaborator, in completing the concerto Patrice had been composing in celebration of the formation of the European Union. After sleeping with Olivier, Julie puts the estate she and her husband owned up for sale and tries to go into hiding, renting a small flat in Paris. But however much she tries to disengage herself from the world around her, Julie keeps being drawn back in. She refuses to sign a neighbor's petition to evict Lucille, a dancer in a strip club, thereby earning Lucille's gratitude. She is sought out by a boy who witnessed the fatal accident and wants to return a gold cross he found at the site and to tell her Patrice's last words -- the punch line to a joke he was telling when he lost control of the car. And she discovers that her husband had a mistress, who is carrying the child he didn't know he had conceived with her. All of this leads Julie to the realization that the liberty she had sought is illusory, that it can't be found in detachment but, to put it in terms of the tricolor, in conjunction with equality and fraternity -- treating Lucille as a equal, for example, and collaborating with Olivier to complete Patrice's concerto, which takes as text for its choral section the verses about love in 1 Corinthians. Visually beautiful with striking use of the titular color throughout, Blue has a romantic glossiness that takes away from the grit and urgency that it might have benefited from.

White (1994)

The middle film of the trilogy is a dark comedy about an exiled Polish hairdresser, Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski), whose French wife, Dominique (Julie Delpy), divorces him because of his impotence. Still desperately in love with Dominique, Karol finds himself homeless, playing tunes on a comb and tissue paper to earn small change in the Métro. Another Pole hears Karol playing a Polish song and strikes up an acquaintance, eventually helping Karol smuggle himself back to Poland in a large suitcase, which is stolen before Karol can emerge from it. After being dumped in a landfill, Karol makes his way home to his brother's beauty parlor, and begins a long process of rehabilitation, in which he makes a fortune, and devises an elaborate plot that involves faking his own death, with which he eventually gets even with Dominique, though the revenge is bittersweet. The screenplay, written by Kieslowski with his usual collaborator, Krzysztof Piesewicz, is ingeniously put together, though the theme of égalité is not quite so central to White as the corresponding color themes are to Blue and Red. Zamachowski is impressive in his journey from victim to victor, but Delpy's role feels somewhat undeveloped. What could have attracted her to this schlub in the first place? As usual, there are some ingenious links between White and the other two films: Juliette Binoche's Julie can be glimpsed entering the courtroom where Karol and Dominique's divorce hearing is taking place, just as in Blue, we caught a glimpse of Delpy and Zamachowski from Julie's point of view in the same setting.

Red (1994)

Not only the last film in the trilogy, Red was also Kieslowski's final film before his death. He had announced his retirement after the release of the film, and died of complications from open-heart surgery in 1996. The film drew three Oscar nominations, for director, screenplay (Kieslowski and Krzysztof Piesewicz), and cinematography (Piotr Sobocinski). It deserved one for Jean-Louis Trintignant's performance as Joseph Kern, a retired judge who spends his time electronically eavesdropping on his neighbors' phone calls. Irène Jacob plays Valentine, a model who encounters Kern when she accidentally hits his dog with her car. The two strike up an unusual friendship as the beautiful young woman draws the misanthropic judge out of his self-imposed exile, ironically by awakening his conscience and causing him to turn himself in to the authorities who convict him of invasion of privacy. In the tricolor scheme, red stands fraternité, and the film delivers on the theme with Kern's emerging empathy. Again, the film links with its predecessors, both of which included scenes in which an elderly person, bent with age, struggles to force a plastic bottle into an aperture in a recycling bin. In Blue, Julie ignored and perhaps didn't even see the person's difficulty; Karol in Red notices but does nothing to help. Only Valentine sees and goes to the person's aid. But I find the ending of Red a little forced, in which the survivors of a disaster at see include not only Valentine, but also Julie and Olivier from Blue, and Karol and Dominique, who have somehow reunited despite the ending of White.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_poster.jpg)

_poster.jpg)