A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Sunday, January 31, 2016

Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Oscar-bashing is an easy game to play, but sometimes it's a necessary one. Double Indemnity was nominated for seven Academy Awards: best picture, best director (Billy Wilder), best actress (Barbara Stanwyck), best screenplay (Wilder and Raymond Chandler), best black-and-white cinematography (John F. Seitz), best scoring (Miklós Rózsa), and best sound recording. It won none of them. The most egregious losses were to the sugary Going My Way, which was named best picture; Leo McCarey won for direction, and Frank Butler and Frank Cavett won for a screenplay that seems impossibly pious and sentimental today. Almost no one watches Going My Way today, whereas Double Indemnity is on a lot of people's lists of favorite films. The reason often cited for Double Indemnity's losses is that it was produced by Paramount, which also produced Going My Way, and that the studio instructed its employees to vote for the latter film. But the Academy always felt uncomfortable with film noir, of which Double Indemnity, a film deeply cynical about human nature, is a prime example. Wilder and Chandler completely reworked James M. Cain's story in their screenplay, and while they were hardly cheerful co-workers (Wilder claimed that he based the alcoholic writer in his 1945 film The Lost Weekend on Chandler), the result was a fine blend of Wilder's bitter wit and Chandler's insight into the twisted nature of the protagonists, Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck) and Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray). And as long as we're on the subject of Oscars, there are the glaring absences of MacMurray and Edward G. Robinson from the nominations -- and not only for this year: Neither actor was ever nominated by the Academy. MacMurray's departure from his usual good-guy roles to play the sleazy, murderous Neff should have been the kind of career about-face the Academy often applauds. And Robinson's dogged, dyspeptic insurance investigator, Barton Keyes, is one of the great character performances in a career notable for them. (The supporting actor Oscar that he should have won went to Barry Fitzgerald's twinkly priest in Going My Way, a part for which Fitzgerald had been, owing to a glitch in the Academy's rules, nominated in both leading and supporting actor categories.)

Saturday, January 30, 2016

Star Wars: Episode VII -- The Force Awakens (J.J. Abrams, 2015)

I don't see movies in theaters anymore: Before yesterday I think the last one I went to was The Avengers (Joss Whedon, 2012) which was kind of a family outing. And I hadn't seen one in 3-D since the last time the process was in vogue, back in the 1950s. But I had to see this one not to be culturally retrograde, and I'm glad I did. To sidetrack to 3-D, I'm not sold on its necessity, partly because the process itself is distracting: I'm always conscious of the screen itself as a kind of frame that cuts things off as they are whizzing into and out of it. In regular old 2-D the frame works to contain the action so you can concentrate on it. I found myself distracted whenever anyone walked into the frame because I was momentarily unsure whether they were part of the film or just someone entering the theater after getting some more popcorn. I think that's why it's a process particularly suited for fast-paced action but not much else. But the movie gave me everything else I wanted, including the warm fuzzy feeling of being reunited with Han (Harrison Ford) and Leia (Carrie Fisher), whose grizzled maturity gave a gravitas to the film. It recaptured the feeling I had back in 1977 at the NorthPark theater in Dallas when John Williams's music struck up and the introductory crawl stretched away into space. Episode VII is essentially a remake of Episode IV, if we must call them that, with the young hero on a desert planet, the droid found in the junkyard, the gathering of a team to fight the black-clad villain, and the ultimate destruction of a giant weaponized space station. It's nice that the hero this time is a woman (Daisy Ridley) and that her cohort includes a black man (John Boyega), both of whom are great in their roles. Oscar Isaac shows once again that he's something of a shapeshifter as an actor: I knew he was in the movie, but I almost didn't recognize him at his first entrance, after having seen him recently as the thwarted Yonkers mayor on HBO's Show Me a Hero (Paul Haggis, 2015). He has the ability to play callow and boyish as well as bitter and brooding, as in Inside Llewyn Davis (Ethan Coen and Joel Coen, 2013). I look forward to seeing the movie again, but this time in the comfort of my home and on a smaller 2-D screen. I think it will play just as well there, thanks more to the smart screenplay by Lawrence Kasdan, J.J. Abrams, and Michael Arndt, and to the well-directed actors, including Adam Driver's Kylo Ren, than to the technological whiz-bang.

Friday, January 29, 2016

Mission: Impossible -- Ghost Protocol (Brad Bird, 2011)

I recently commented here that I didn't respond particularly well to Gregory Peck because, unlike stars such as Cary Grant and Bette Davis, he never surprised me with a line reading or a facial expression. I think the same is true of Tom Cruise, whose range seems to be limited to intensity: He never seems to unclench. That becomes apparent in this fourth installment of the Mission: Impossible series when he shares the screen with a much more versatile star, Jeremy Renner, who can be both intense and casually self-deprecating. I'm not saying Cruise is a bad actor: I thought his performance in Rain Man (Barry Levinson, 1988) was superior to Dustin Hoffman's Oscar-winning one. All Hoffman had to do was find a shtick and stay with it; Cruise was the one who had to grow and change over the course of the movie. It's just that he built his career on muscular action and a captivating grin that grew into a rictus as his career thrived. This Mission film is, I think, superior to the first three because it doesn't take on more than it can handle. It turns its heroes -- Cruise, Renner, Simon Pegg, Paula Patton -- into fallible beings who screw up but manage to get on the right course at the last minute. It's all familiar super-action stuff, of the kind we've seen and marveled at ever since James Bond hit the screen. Renner and Pegg especially are instrumental in saving the movie from tedium, especially in their interplay in the sequence when Renner is called on to reprise the famous drop to within an inch of danger that Cruise did in the first Mission film back in 1996. This time, Renner has to do it with no restraint, free-falling until a magnet repels his magnetized suit, and both Renner and Pegg play it for laughs, something that director Brad Bird is skilled at providing. The screenplay (by Josh Appelbaum and André Nemec) tries to build some suspense around a secret that Renner's character, Brandt, is hiding from Cruise's Ethan Hunt, but that's just filler between action sequences.

Thursday, January 28, 2016

Only Angels Have Wings (Howard Hawks, 1939)

|

| Cary Grant and Jean Arthur in Only Angels Have Wings |

Bonnie Lee: Jean Arthur

Bat McPherson: Richard Barthelmess

Judy McPherson: Rita Hayworth

Kid Dabb: Thomas Mitchell

Lee Peters: Allyn Joslyn

Dutchy: Sig Ruman

Director: Howard Hawks

Screenplay: Jules Furthman

Cinematography: Joseph Walker

Art direction: Lionel Banks

Film editing: Viola Lawrence

Music: Dimitri Tiomkin

Thomas Mitchell had begun his acting career on stage, making his Broadway debut in 1916. It would be 20 years before he decided to leave the stage for Hollywood, and three years after settling there he found himself performing in no fewer than five of 1939's top movies: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (William Dieterle), Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra), Stagecoach (John Ford), and Only Angels Have Wings. He won an Oscar for Stagecoach, and four of the five films in which he appeared were nominated for the best picture Oscar. As it happens, the one film that didn't get nominated, Only Angels Have Wings, is my favorite of the bunch. That it wasn't nominated may have had something to do with its director, Howard Hawks, who refused to be tied down to any one of the major studios, feeling that he had been burned by a dispute with production head Irving Thalberg at MGM. For the rest of his career he made the rounds of the studios, producing and directing (and often writing without credit) some of the most enjoyable movies ever made. But he was nominated for the best director Oscar only once, for Sergeant York (1941), which has its Hawksian touches -- fast-paced dialogue and deft use of character players like Walter Brennan, Margaret Wycherly, Ward Bond, and Noah Beery Jr. -- but is more sentimental than typical Hawks films. In fact, Hawks must hold some kind of record for classic films that received no Oscar nominations at all, including the great gangster film Scarface (1930) and the dizziest of screwball comedies -- Twentieth Century (1934), Bringing Up Baby (1938), and His Girl Friday (1940) -- as well as the definitive Marilyn Monroe vehicle, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and the films that stand as landmarks in the careers of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, To Have and Have Not (1944) and The Big Sleep (1946). He finally got an honorary Oscar in 1975, after having been discovered by the French critics of Cahiers du Cinéma and American auteurist critics like Andrew Sarris. Only Angels is prime Hawks, with a sterling cast that includes not only Mitchell, as the aging pilot known as "Kid," but also Cary Grant and Jean Arthur. They bring a touch of the screwball comedy at which they excelled to what is essentially a serious story about the grace under pressure shown by fliers in a small South American port town who have to battle the weather to fly the mail across the Andes. Hawks and screenwriter Jules Furthman take the familiar "you can't send the kid up in a crate like that" premise and turn into something both funny and moving. The key is that that they refuse, like the pilots in their movie, to take anything really seriously, so the light touch keeps the peril and loss from bogging the film down. There is a startling moment near the end when we see tears in Grant's eyes, but the movie swiftly moves to a lighter-hearted conclusion. There is some corny artifice in the settings and flying sequences, and perhaps a little too much about the relationship between the characters played by Rita Hayworth (pushed on Hawks by Columbia studio head Harry Cohn) and Richard Barthelmess. Some see Only Angels as a kind of rough draft for To Have and Have Not, and Jean Arthur, who clashed with Hawks about her character, said she didn't understand what he wanted until he saw that later film. But Only Angels Have Wings stands on its own.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (Preston Sturges, 1947)

The sad finale of two great Hollywood careers: Harold Lloyd's and Preston Sturges's. One of the great silent comedians, Lloyd had been making movies since 1913, but like so many stars of silent films he failed to make an impression in talkies and retired from movies in 1938. Sturges, who was starting up a new studio, California Pictures, with Howard Hughes, persuaded Lloyd to come out of retirement as a producer and director for the studio, but as so often happened when Hughes had a hand in things, nothing worked out right for either Sturges or Lloyd. Sturges had had a run as writer-director of seven comedies, from The Great McGinty in 1940 through Hail the Conquering Hero in 1944, that are some of the greatest ever made in Hollywood, but his attempt at a serious movie, The Great Moment (1944), was a major flop that led to his departure from Paramount and into his partnership with Hughes. Unfortunately, tensions with both Hughes and Lloyd over The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, which Lloyd had been led to believe he would direct, contributed to the poor marketing and release of the movie. Its failure at the box office caused Hughes to pull it and to re-edit it into a shorter film renamed Mad Wednesday, which also failed. Lloyd never acted in another movie, and although Sturges wrote and directed three more, only Unfaithfully Yours (1948) has the comic finesse of his great 1940-44 films. It, too, was a box office flop, though it is now regarded by many as a late masterpiece. The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, unfortunately, is no masterpiece, though it has some good moments. Many of Sturges's great company of character players are in the film, including Jimmy Conlin, Raymond Walburn, Rudy Vallee, Franklin Pangborn, and Robert Dudley, and the scenes in which they appear are invariably the best. It's perhaps unfortunate that Sturges chose to open the film with an excerpt from Lloyd's silent classic, The Freshman (Fred C. Newmeyer and Sam Taylor, 1925), because the slapstick sequences that follow in Sturges's part of the film pale in comparison. The central knockabout comedy scene in the film involves Lloyd, Conlin, and a lion stuck precariously on the ledge of a building; it recalls the classic skyscraper sequence in Lloyd's Safety Last! (Newmeyer and Taylor, 1923), but the gag becomes overextended and glaringly improbable in this version.

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Sullivan's Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941)

Let us now praise Joel McCrea, who never became an icon like Cooper or Gable or Grant or Stewart, but could always be relied on for a fine performance when the others weren't available. He starred in two of Sturges's best, the other one being The Palm Beach Story (1942), and gave solid and sometimes memorable performances for William Wyler (Dead End, 1937), Cecil B. DeMille (Union Pacific, 1939), Alfred Hitchcock (Foreign Correspondent, 1940), and George Stevens (The More the Merrier, 1943) before becoming a durable fixture in Westerns. His performance in the title role of Sullivan's Travels is just what the movie needed: an actor who could do slapstick comedy but turn serious when necessary, a task that among major stars of the era perhaps only Cary Grant and Henry Fonda -- the Fonda of Sturges's own The Lady Eve (1941) -- were also really good at. The genius of Sullivan's Travels is that its serious parts jibe so well with its goofy ones. As Sturges has characters warn Sullivan at the beginning of his scheme to pose as a hobo to get material for his turn as a "serious" director, poor people don't like to be condescended to. The pivotal scene of the film is the one in which the convicts go to a black church to watch a movie. It could have been an embarrassing display of the era's racial stereotypes, but Sturges handles it with tact and sensitivity, so that it becomes emotionally effective and brings home the dual points about charity and the need for humor without excessive sentimentality and preachiness. Sturges's usual gang of brilliant character players -- including William Demarest, Franklin Pangborn, Porter Hall, Eric Blore, and Jimmy Conlin -- are on hand. Sturges and McCrea found working with Veronica Lake a pain, but fortunately it doesn't show.

Monday, January 25, 2016

The End of Summer (Yasujiro Ozu, 1961)

I would call Ozu the most "Chekhovian" of filmmakers because his movies really do remind me of Chekhov's plays. But the adjective has been so overused to the point that all it seems to mean is "a melancholy character study with a little humor, no action, and not much plot." That is, of course, true of The End of Summer, but it doesn't come close to capturing the effect of the film, the sense of having spent privileged moments with people as they go through the universal experiences of living: love, disappointment, death, reconciliation, coping with the past, and so on. It's about the Kohayagawa family, who run a small sake brewery that's in financial difficulties, partly because the patriarch, Manbei (Ganjiro Nakamura), has lost interest in the company. In his old age, he has rediscovered a former mistress, Sasaki (Chieko Naniwa), whose 21-year-old daughter, Yuriko (Reiko Dan), may be his own child. She's a flighty young thing who has a couple of American boyfriends and really hopes only to get a mink stole out of Manbei. Meanwhile, his own family struggles to figure out what to do with the business and how to keep track of Manbei, sometimes sending out employees to follow him on his excursions to see Sasaki. Manbei has two daughters, Fumiko (Michiyo Aratama) and Noriko (Yoko Tsukasa), as well as a daughter-in-law, Akiko (Setsuko Hara), his son's widow. Fumiko is married, and Manbei wants to get Noriko and Akiko married off before he dies, so he asks his brother-in-law, Kitagawa (Daisuke Kato), to find husbands for them. Neither woman is particularly interested in Kitagawa's picks, but they go through the motions to please Manbei. Like I said, not much plot, but Ozu and co-screenwriter Kogo Noda make the most of the characters, particularly Manbei himself, whom Nakamura turns into an endearing scamp. As often in Ozu's films, there are peripheral characters who serve as a kind of chorus: In this case, it's a couple of farmers (Chishu Ryu, who appeared in almost all of Ozu's films, and Yuko Mochizuki) who watch the funeral procession at the film's end and provide the appropriate comment about the "cycle of life."

Sunday, January 24, 2016

Equinox Flower (Yasujiro Ozu, 1958)

Equinox Flower is Ozu's first color film. Once again he lagged behind film industry trends -- the first color film in Japan was made in 1951 -- and managed to anger the Japanese film industry by using the German-made Agfa color process instead of Fuji film because he thought the reds in Agfa film were truer. American viewers may be struck by how the movie often seems to be a Japanese translation of the American family comedy: think Father of the Bride (Vincente Minnelli, 1950). It centers on Wataru Hirayama (Shin Saburi), who finds his wife and daughters scheming against him when he insists on arranging the marriage of his elder daughter, Setsuko (Ineko Arima). When a young man he has never met before, Masahiko Taniguchi (Keiji Sada), comes to his office one day to ask for Setsuko's hand, Hirayama is furious, and not only forbids the marriage but also insists that Setsuko, who has met Taniguchi at the place where she works, be confined to home. Eventually, things work out for the young couple, but not before Hirayama has learned a lesson about the way the roles of the sexes have changed in Japan. In fact, when we first see Hirayama, he is giving a speech at a wedding, indicating his preference for parental approval and noting that even though their own marriage had been arranged, he and his wife, Kiyoko (Kinuyo Tanaka), who is sitting silently beside him, made a go of it. We will soon learn that Kiyoko is not quite so submissive as she seems. The bite that underlies this quite charming comedy lies in its portrayal of the post-war Japanese male, the warrior turned salaryman, most effectively seen in an episode in which Hirayama, after reluctantly attending the wedding of Setsuko and Taniguchi, goes to a reunion of his old classmates, who sing songs about the glory of the Japanese warrior though their own lives consist of office work and golf. The screenplay by Ozu and Kogo Noda was based on a novel by Ton Satomi. The cinematographer was Yuharu Atsuta.

A Story of Floating Weeds (Yasujiro Ozu, 1934)

|

| Tomio Aoki in A Story of Floating Weeds |

Otsune: Choko Iida

Shinkichi: Koji Mitsui

Otaka: Rieko Yagumo

Otoki: Yoshiko Tsubouchi

Tomi-boh: Tomio Aoki

Tomibo's Father: Reiko Tani

Director: Yasujiro Ozu

Screenplay: Tadao Ikeda, Yasujiro Ozu

Cinematography: Hideo Shigehara

Art direction: Tatsuo Hamada

This is the first, silent version of a film that Ozu remade with sound and in color in 1959, when it was released as Floating Weeds. Yes, 1934 is late to be making silent films, but Ozu was following the lead of the Japanese film industry, which didn't switch to sound until 1931 -- and Ozu waited till 1936 to make a talkie. It's the story (written by Tadao Ikeda and Ozu himself under his pseudonym James Maki) of Kihachi Ichikawa, the head of a troupe of traveling players who find themselves in a village where Kihachi has a former mistress, Otsune, with whom he had a son, Shinkichi. The now almost-grown son has always known Kihachi as "Uncle," because Kihachi has kept his parentage secret, not wanting him to follow in his footsteps as an actor. But when Otaka, an actress in the troupe and Kihachi's most recent mistress, discovers the secret, she decides to take revenge by asking a younger actress, Otoki, to seduce Shinkichi. The revenge backfires when Otoki falls in love with the young man. As usual, Ozu's sympathetic view of human relationships carries the film, giving depth to the somewhat slight story. And the glimpses of the world of the traveling players is both fascinating and funny. The lovely cinematography is by Hideo Shigehara, who filmed and sometimes edited many of Ozu's pre-war movies.

Saturday, January 23, 2016

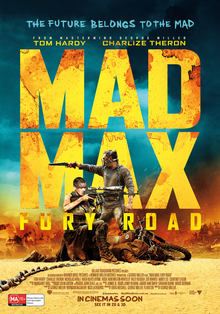

Mad Max: Fury Road (George Miller, 2015)

If only all action movies could be directed by George Miller and edited by Margaret Sixel. Then we might have fewer scenes shot in the dark with shakycam and patched together out of snippets of film so you can't really tell who's fighting whom. Or much less gratuitous use of CGI in scenes where actual hardware provides greater immediacy than software can ever do. Miller and Sixel are one of the movies' great husband-and-wife teams, and it's gratifying that they've both been nominated for Oscars for Mad Max: Fury Road. I've never been much of a fan of the Mad Max series, but this one, the fourth, seems to me to be the best and most coherent. It has the kind of visual storytelling that takes you back to the silent roots of the movies. It also features, in Charlize Theron's Furiosa, the best female action hero since Sigourney Weaver's Ripley in Aliens (James Cameron, 1986). I don't expect the movie to win the best picture Oscar: It's not the kind of film the Academy admires, preferring action movies that are wrapped in history, like Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962), or sanctified by religiosity, like Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959). Fury Road is sheer enjoyable nonsense, with an abundance of grotesque villains and some heroes who, with the exception of Tom Hardy's Max and Nicholas Hoult's Nux, happen to be women. But I hope it takes home Oscars for John Seale's cinematography, Jenny Beavan's costumes, and for production design and visual effects. And I wouldn't mind if Miller and Sixel won, too.

Friday, January 22, 2016

Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967)

Calling a film a landmark, as Bonnie and Clyde so often has been called, does it a disservice in that it prioritizes historical significance over the aesthetic ones. It makes it difficult to appreciate or criticize the movie without recalling what it was like to see and to talk about the first time you saw it -- if, like me, you saw it in a theater when it was first released. It's a landmark because its success showed the Hollywood studios, which were mere surviving remnants of the old movie factories of the '30s and '40s, that there was an audience for something other than the big musicals and epics that had dominated American movies during the 1960s. There was a young audience out there that had grown up with the French New Wave and the great Italian and Japanese films of that decade, and was resistant to piety and platitudes. Along with The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967), Bonnie and Clyde gave this audience something they were looking for, and fed the revolution in filmmaking that made the 1970s one of the most adventurous decades in film history. It's no surprise that the screenwriters, Robert Benton and David Newman, were so familiar with the New Wave that they wanted François Truffaut or Jean-Luc Godard to direct their movie. And even today Warren Beatty, in the opening scenes of Bonnie and Clyde, is bound to remind one of Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless (Godard, 1960). It was a movie that launched the careers of Faye Dunaway and Gene Hackman, not to mention giving Beatty a boost into superstardom. It also put an end to some careers, most notably that of Bosley Crowther, who had been the New York Times's film critic since 1940 but was undone by his vitriolic attack on Bonnie and Clyde, which he denounced not only in his initial review but also, after protests from the movie's admirers, in two subsequent articles. Crowther was replaced as the Times critic in 1968. On the other hand, Newsweek's critic, Joe Morgenstern, initially panned the film but, after being urged by readers to reconsider, recanted his original critique. So the question persists: Historical significance aside, is Bonnie and Clyde really any good? I'd have to say, after seeing it again for the first time in many years, that it holds up as entertainment. The acting is superb, and Burnett Guffey's cinematography, Dean Tavoularis's art direction, and Theadora van Runkle's costuming all provide a fine 1960s interpretation of 1930s style. Where it falls down for me is in substance: The screenplay, which was worked over by Robert Towne, is too preoccupied with Bonnie and Clyde as lovers with (especially Clyde) some psychosexual hangups. It only feints at demonstrating why the pair became cult figures in the Great Depression, most notably in a scene when Clyde refuses to take the money of a farmer who is in the bank they're robbing, and in a scene in which the wounded couple and C.W. Moss (endearingly played by Michael J. Pollard) stop for help at a bleak migrant camp. Only in scenes like these do we get a sense of the deep background of Depression-era misery, a fuller treatment of which might have elevated the film into greatness, the way Francis Ford Coppola's first two Godfather films (1972, 1974) turned Mario Puzo's popular novel into an American myth. Otherwise, the criticism that it glamorizes the outlaws by turning them into fashion-model beauties still has some merit.

Thursday, January 21, 2016

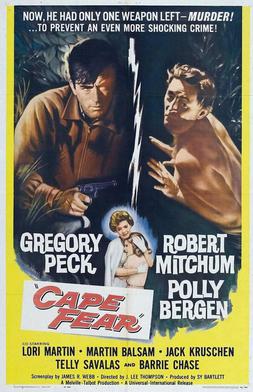

Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1962)

When I watched Martin Scorsese's 1991 remake of this movie, I commented that I hadn't seen Lee Thompson's 1962 version and didn't know why Scorsese would want to remake it. And now that I've seen it, I still don't know. This earlier version, with a screenplay by James R. Webb from the same John D. MacDonald novel, The Executioners, is a tense, well-cast movie with the same Bernard Herrmann soundtrack that Scorsese had Elmer Bernstein adapt for his version. What Scorsese's screenwriter, Wesley Strick, did was to add more complications to the characters in the later film. Gregory Peck's Sam Bowden is a straight arrow compared to Nick Nolte's, and both Jessica Lange and Juliette Lange bring greater depth to Bowden's wife and daughter than Polly Bergen and Lori Martin do in the earlier version. But given that the movie in both cases is essentially a suspense thriller, I'm not sure that this is necessarily an improvement: The earlier film's emphasis on the innocence of the Bowdens makes the threat posed by Robert Mitchum's Max Cady more intense than that posed by Robert De Niro to the more morally compromised Bowdens of the Scorsese film. So in short, I have to say I prefer the earlier version. No one is saying that Lee Thompson was a better director, or that the screenwriter and actors in his version are superior to Scorsese and company. But if the intent of the film is to shock and to have the audience on the edge of their seats, then the earlier version does the job better. I have never been a fan of Gregory Peck, who is an actor who never surprises me with a line delivery or facial expression, as Nolte has been known to do, and Bergen and Martin are decidedly inferior to Lange and Lewis as actors, but they make better victims, which is all that the movie asks of them. The one performance that seems to me superior is Mitchum's, perhaps because there is a brutishness in his very persona that is lacking in De Niro, who has many film personae. I think De Niro overacts feverishly to make his Cady menacing, at the expense of becoming ludicrous. Mitchum, on the other hand, has only to narrow his sleepy eyes to suggest the deep psychosis of his character, and his menacing of Bergen, in which Mitchum apparently improvised the device of breaking an egg and smearing her with it, is truly chilling. Although Lee Thompson's final sequence, in which Cady sneaks up on the Bowdens' houseboat, is somewhat botched -- we're never quite sure where Cady, Bowden, and the detective assigned to guard them are at any given moment -- I still think it's preferable to the special-effects-laden storm that destroys the houseboat in Scorsese's film. Lee Thompson, whose only other really memorable film was The Guns of Navarone (1961), was never the filmmaker that Scorsese is, but here I think he does a better job of keeping the audience on edge.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

Swamp Water (Jean Renoir, 1941)

Swamp Water has a few things working against it other than its title. For one, having a cast of familiar Hollywood stars pretending to be farmers, hunters, and trappers living on the edge of the Okefenokee swamp, and saying things like "I brung her" and "He got losted," makes for a certain lack of authenticity. And at 32, its leading man, Dana Andrews is about a decade too old to be playing the callow youth he's supposed to be in the movie. Add to that the director, Jean Renoir, is a wartime exile from France, making his first film in Hollywood, and you might expect the worst. Fortunately, it has a screenplay by a master, Dudley Nichols, and an eminently watchable cast that includes Walter Brennan, Walter Huston, Anne Baxter, John Carradine, Ward Bond, and Eugene Pallette, who while they may never quite convince us that they're Georgia swamp-folk, do their professional best. It turns out to be a thoroughly entertaining movie that, while it doesn't add any luster to Renoir's career, doesn't detract from it either. This was Andrews's second year in movies, and he gives the kind of energetic performance that mostly overcomes miscasting. Born in Mississippi and raised in Texas, he also seems to know the character he's called on to play, perhaps a little better than the city-bred Baxter, whose efforts at being the village outcast are a bit forced. Brennan as usual plays an old coot, but without overdoing the mannerisms -- it's a slyly engaging performance. Much of the footage was shot by cinematographer J. Peverell Marley and the uncredited Lucien Ballard in the actual swamp and environs near Waycross, Georgia. There is some obvious failure to match the location footage with that shot back in the 20th Century-Fox studio, but it's not terribly distracting.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Sadie Thompson (Raoul Walsh, 1928)

It's sad that most people know Gloria Swanson only as the gorgon Norma Desmond in Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1957). Or that Swanson's deft parody of silent movie acting in that film constitutes many people's impression of what it was like. The survival of Sadie Thompson, even though it's missing its last reel, which the restorers piece out with old stills and title cards, shows what a formidable force Swanson could be on screen, generating enough heat that it's surprising she didn't ignite the nitrate film stock. The story is the familiar one of the San Francisco prostitute who comes to Pago Pago, where she clashes with a bluenose reformer who threatens to return her to San Francisco and the hands of the police. The reformer is Alfred Davidson (Lionel Barrymore in full ham), who was a clergyman in Somerset Maugham's short story, "Miss Thompson," and the play, Rain, that was based on it, but becomes a layman here to please the Hays Office. Fortunately, Sadie has the support of a sturdy young Marine sergeant, Timothy O'Hara, played by director Raoul Walsh, who before turning director full-time had been an actor in the early days of silents; he played John Wilkes Booth in The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915). This brief return to acting was a one-shot: Walsh was planning to direct himself again in In Old Arizona (Irving Cummings, 1928), but lost his right eye in a freak auto accident while on location preparing to shoot the film; Warner Baxter took over the role and won an Oscar for it. Swanson was nominated for an Oscar for Sadie Thompson, as was cinematographer George Barnes, whose nomination included his work on two other films: The Devil Dancer (Fred Niblo, 1927) and The Magic Flame (Henry King, 1927). In fact, Barnes did only a week's worth of filming on Sadie Thompson before Samuel Goldwyn insisted he fulfill a contractual obligation to him; he was replaced by Robert Kurrle and Oliver T. Marsh.

Two Arabian Knights (Lewis Milestone, 1927)

The first ever Academy Awards, presented in 1929 for movies made in 1927 and 1928, included several categories that soon disappeared. There was one for "title writing," which the arrival of sound made obsolete, and the award for best picture was divided into two categories: "best production" and "unique and artistic production." The former was won by Wings (William A. Wellman, 1927), the latter by Sunrise (F.W. Murnau, 1927). The distinction between "best" and "unique and artistic" is opaque, so the Academy dropped the latter category the next year. But one category split that it might well have retained, given the Academy's blindness toward comedy over the years, was the distinction between "director, comedy picture," and "director, dramatic picture." Lewis Milestone became the sole winner of the former award, but he might have missed out on that opportunity if the Academy hadn't excluded Charles Chaplin from competition. Chaplin was instead given a special award as writer, director, producer, and star of The Circus (1928), probably because the Academy board knew that he would have swept the honors if allowed to compete for them. The trouble is, Two Arabian Knights is not terribly funny. It's a series of bits about two raffish American soldiers in World War I, who escape from a German prison camp and through a series of improbable circumstances wind up in "Arabia," where they rescue the daughter of an emir from marriage to a man she doesn't love. It's the stuff every Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Dorothy Lamour movie was made of, but without the talent and charisma. The soldiers are a high-born Philadelphian, W. Daingerfield Phelps III (William Boyd) and his sergeant, a New York cabbie named O'Gaffney (Louis Wolheim). The emir's daughter is played by Mary Astor, who has little to do besides roll her eyes over her veil. Milestone and Wolheim would be reunited, with much better results, in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Boyd was a popular leading man in silents and early talkies, but he fell on hard times before, in 1935, he landed a role in a Western as a character named Hopalong Cassidy. He played the part for the next two decades in scores of movies and a TV series. Two Arabian Knights also features Boris Karloff in a small role.

Monday, January 18, 2016

Her Night of Romance (Sidney Franklin, 1924)

They had faces then, as the saying goes. And they needed them because they didn't have voices. Constance Talmadge was not beautiful -- her heart-shaped face was too long, and the profile shots in Her Night of Romance reveal the beginnings of a double chin. It's suggestive that when we first see her in the movie, she is pretending to be ugly -- and succeeding in a hilarious way: When ordered by newspaper photographers to smile and show her teeth, she comes up with a grimace that looks like she's just bitten into a lemon. But she had huge eyes and knew how to act with them, showing what she was thinking -- and often what she was saying. The ugly duckling masquerade is prescribed by the plot, in which she is an American heiress arriving in England and trying to duck fortune-hunters. Naturally the first person who sees through her disguise is an impoverished lord (Ronald Colman), who has just put his mansion up for sale, so the plot (by Hanns Kräly) becomes a series of complications after her father (Albert Gran) buys the mansion. The rest is a series of mistaken identities and misunderstood motives common to romantic comedy. Colman was nearing the peak of the first phase of his career as a movie star, relying on his suave handsomeness and good comic timing. It was a career that lasted 40 years because, unlike many silent stars, he had a speaking voice that was as handsome as his face. Talmadge and her sister Norma, who was also a major silent star, were not so lucky: Neither had received vocal training that would have helped them lose their Brooklyn accents, so they left movies when sound arrived.

Sunday, January 17, 2016

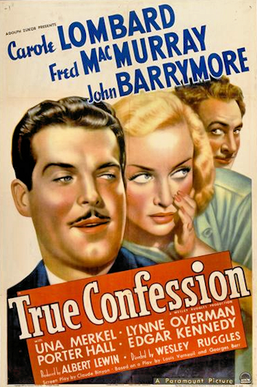

True Confession (Wesley Ruggles, 1937)

A somewhat too frantic screwball comedy, True Confession plays fast and loose not only with the legal profession but also to an extent with the careers of its stars. Fred MacMurray plays Kenneth Bartlett, a lawyer who insists on defending only those he thinks are really innocent, which gives him some trouble when his wife, Helen (Carole Lombard), goes on trial for murder. She's a would-be writer who can't always be trusted to tell the truth, so even though she didn't commit the crime, she winds up saying she did and pleading self-defense. Meanwhile, the trial is being watched by Charley Jasper (John Barrymore), an alcoholic loon who knows who really did the deed. None of these people make much sense, especially Barrymore, who seems at times to be reprising his earlier, far more successful performance as Oscar Jaffe opposite Lombard's Lily Garland (aka Mildred Plotka) in Twentieth Century (Howard Hawks, 1934). Alcohol had taken a serious toll on Barrymore, who was 55 when he made this film; he looks 70. Lombard was better, more controlled in her comic flights in Twentieth Century, too. Here she verges on grating at times. Comparisons are seldom fair, but it has to be said that the difference between the two films has to be that the earlier and better one was directed by Hawks from a screenplay by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, and True Confession was directed by Wesley Ruggles from a screenplay by Claude Binyon based on a French farce. Still, there's some fun to be had here, and the cast includes such stars from the golden age of character actors as Una Merkel being giddy, Porter Hall being irascible, Edgar Kennedy doing multiple face-palms, and Hattie McDaniel playing one of her always watchable (if regrettable) roles as the maid.

The River (Jean Renoir, 1951)

The near-hallucinatory vividness of Technicolor was seemingly made for Jean Renoir, the son of the Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, but this film was his first use of the process. It's the more remarkable because he was working with his nephew (and Pierre-Auguste's grandson), Claude Renoir, the cinematographer, and neither director nor photographer was particularly experienced in shooting landscape, especially in the country of India, which is the real star of the film. The River has a distinctly Western attitude toward the country, viewing it through the eyes of its British residents. It's based on the experiences of Rumer Godden, the English writer who spent her childhood in India. Her screenplay, co-written with Jean Renoir, is about the tensions between cultures, using the Ganges, the titular river, as a symbol of both the eternal and the mutable. Ravishingly beautiful as the film is, it suffers from some major weaknesses in casting. Its central character, the teenager Harriet, is played by Patricia Walters, a nonprofessional who made no subsequent films and never quite seems at ease before the camera. As Capt. John, the American recovering from the loss of a leg during the war, Thomas E. Breen doesn't have the kind of charisma that would seem to have Harriet, her older friend Valerie (Adrienne Corri), and her Eurasian neighbor (Radha Burnier) falling over themselves to attract his attention. (Breen, incidentally, was both a real amputee from a war wound and the son of the enforcer of the Production Code, Joseph I. Breen.) But for those willing to overlook its flaws, which also include a lack of narrative urgency, The River rewards sympathetic attention and, as a film by a Frenchman about the English in India, stands as a landmark in postwar international filmmaking.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

La Pointe Courte (Agnès Varda, 1955)

|

| Philippe Noiret in La Pointe Courte |

Elle: Silvia Monfort

Director: Agnès Varda

Screenplay: Agnès Varda

Cinematography: Louis Soulanes, Paul Soulignac, Louis Stein

Film editing: Alain Resnais

Music: Pierre Barbaud

"They talk too much to be happy," says one of the villagers about the Parisian couple (Philippe Noiret and Silvia Monfort) who are spending time in a small fishing community on the Mediterranean. He has been in the town, where he was born, for several weeks, and she arrives to tell him that she wants a separation after four years of marriage. So they wander around, endlessly analyzing their relationship, as life goes on in the village: The townspeople argue with the authorities about where they can fish and about the bacterial count that has been detected in the water; a small child dies; a young man courts a girl over the objections of her father; a festival that involves jousting from boats takes place, and so on. The sophisticated self-analysis of the couple soon begins to look petty against the backdrop of the village's real problems. At one point in their dialogue, a scene is stolen from them by one of the village's many cats, whose playing around on a woodpile behind the couple becomes far more interesting than what they have to say. Aside from Noiret and Monfort, the actors are all actual residents of the village. Varda began as a still photographer, and her sense of composition is notable throughout this film, her first. She had spent time in Sète, the town where La Pointe Courte was filmed, as a teenager, and was photographing it for a friend when the idea of the movie came to her. It's often cited as one of the first films of the French New Wave, of which she became a prominent member, though seven years passed before she made her second and better-known film, Cléo From 5 to 7 (1962). Alain Resnais, who became one of the leading New Wave directors, edited La Pointe Courte, and the striking score is by Pierre Barbaud.

Night and Fog (Alain Resnais, 1955)

Cynics used to say that the surest way to win an Oscar for best documentary was to make a film about the Holocaust. But when Alain Resnais's Night and Fog was released, it not only received no Oscar nominations, but it was confronted by protests. The German government wanted it to be withdrawn from exhibition at the Cannes Film Festival, and the French censors objected to a scene in which a French police officer was shown guarding one of the deportation centers run by the Vichy government during the war. The French censors also objected to a sequence showing bodies being bulldozed into a mass grave. But it's a testimony to the power of Resnais's editing and the narrative written by Jean Cayrol, a survivor of the Mauthausen-Gusen camp, and spoken by Michel Bouquet, that although such images have grown distressingly familiar over the past 60 years, they still have their power to shock the conscience. It sounds tediously moralizing to reiterate, but every time a politician today tries to dehumanize whatever group is currently out of favor, these images should come to mind.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

I remember the long dorm-room discussion after my friends and I saw this film for the first time, so I was surprised on returning to it after so many years how conventional the elements we talked about now seem. The extended use of documentary clips at the beginning of the film, with the voiceover by the lovers (Emmanuelle Riva and Eiji Okada) arguing about whether she had really seen anything in Hiroshima, seemed to us a bafflingly random way to start a movie. The jump cuts into and out of flashbacks confused us. What, we argued, did it signify that their entwined bodies, seemingly covered with ashes, then began to glow? (Today, I'm afraid some sarcastic voice will pipe up to say, "They've been glitter-bombed.") Why does she refer to her Japanese lover as "you" when she's actually talking about the German she loved during the war? Is the movie really about sleeping with the enemy? Doesn't it trivialize the horror of Hiroshima to bring it down to the level of the background for a love affair? Today, we'd regard those questions as naive, and I'm certain we wouldn't be confused by the film's structure, which is a way of saying that Resnais and his screenwriter, Marguerite Duras, really did succeed in revolutionizing movies. But if no one is startled by jump cuts or unconventional narrative devices today, there remains a raw immediacy about the film that no subsequent imitators have ever quite succeeded in equaling. Much credit also has to go to the score by Georges Delerue and Giovanni Fusco, and to the editing by Michio Takahashi and Sacha Vierny.

Far From the Madding Crowd (Thomas Vinterberg, 2015)

It's not really easy for me to comment on one version of the Thomas Hardy novel after just commenting on another without resorting to comparisons, so I won't even try to avoid them. One unavoidably obvious difference between the 2015 film and the 1967 John Schlesinger version is visual. In Schlesinger's film, despite the fine cinematography of Nicolas Roeg, the interiors seem impossibly overlighted for a period that resorted to candles and oil lamps for illumination. The change in film technology now makes it possible for us to see the way people once lived -- in a realm of darkness and shadows. (We can almost precisely date when this change in cinematography took place: in 1975, when director Stanley Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott worked with lenses specially designed for NASA to create accurately lighted interiors for Barry Lyndon. Since then, the digital revolution has only added to the arsenal of lighting effects available to filmmakers.) So cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen's adds an element of texture and mystery to Thomas Vinterberg's version that was technologically unavailable to Roeg, and not only in interiors but also in night scenes, such as the first encounter of Bathsheba (Carey Mulligan) and Sgt. Troy (Tom Sturridge), when he gets his spur caught in the hem of her dress. The scene is meant to take place by the light of the lamp she is carrying, which Christensen accomplishes more successfully than Roeg was able to. But the story's the thing, and David Nicholls's screenplay is much tighter than Frederic Raphael's 1967 version -- it's also about an hour shorter. Nicholls makes most of his cuts toward the end of the film, omitting for example the episode in which Troy becomes a circus performer, one of the more entertaining sections of the Schlesinger-Raphael version. I think Nicholls's screenplay sets up the early part of the stories of Bathsheba and Gabriel Oak (Matthias Schoenaerts) much better, though he has to resort to a brief voiceover by Mulligan at the beginning to make things clear. His account of the affair of Troy and the ill-fated Fanny Robbin (Juno Temple) is less dramatically detailed than Raphael's, but in neither film is their relationship dealt with clearly enough to make us understand Troy's character. On the whole, I think I prefer the new version, which is less star-driven than Schlesinger's, but I can't really say whether I would feel that way if I had seen the new one first.

Thursday, January 14, 2016

Far From the Madding Crowd (John Schlesinger, 1967)

People always complain about the way movies change the stories of their favorite novels, but screenwriter Frederic Raphael's adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel shows why such changes are necessary. Raphael remains faithful to the plot, with the result that characters become far more enigmatic than Hardy intended them to be. We need more of the backstories of Bathsheba Everdeen (Julie Christie), Gabriel Oak (Alan Bates), William Boldwood (Peter Finch), and Frank Troy (Terence Stamp) than the highly capable actors who play them can give us, even in a movie that runs for three hours -- including an overture, an intermission, and an "entr'acte." These trimmings are signs that the producers wanted a prestige blockbuster like Doctor Zhivago (David Lean, 1965), which had also starred Christie. But Hardy's works, with their characters dogged by fate and chance, don't much lend themselves to epic treatment. John Schlesinger, a director very much at home in the cynical milieus of London in Darling (1965) and Sunday Bloody Sunday (1971) and New York in Midnight Cowboy (1969), doesn't show much feeling for Hardy's rural, isolated Wessex, where the weight of tradition and the indifference of nature play substantial roles. What atmosphere the film has comes from cinematographer Nicolas Roeg's images of the Dorset and Wiltshire countryside and from Richard Rodney Bennett's score, which received the film's only Oscar nomination.

Wednesday, January 13, 2016

The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946)

It's one of the most memorable entrances in movies. Actually, her lipstick enters first, rolling across the floor toward him. She is Cora Smith and he is Frank Chambers, the man her husband has just hired to work in their roadside café/filling station. But more important, she is Lana Turner, one of the last of the products of the resources of the studio star factories: lighting, hair, makeup, wardrobe, and especially public relations. And he is John Garfield, one of the first of a new generation of Hollywood leading men, trained on the stage, and with an urban ethnicity about him: His vaguely presidential nom de théâtre thinly disguises his birth name, Jacob Julius Garfinkle. The pairing shouldn't work: She's a goddess, not an actress, whom the publicists had turned into "the Sweater Girl" while claiming that she had been discovered at a drugstore soda fountain. He was the child of Ukrainian-born Jews and grew up on the Lower East Side, trained as a boxer and studied acting with various disciples of Stanislavsky. But the chemistry is there from the moment Frank picks up Cora's lipstick and the camera surveys her from toe to head: white shoes, tan legs, white shorts, tan midriff, white halter top, blond hair, white turban. She reaches out her hand for the lipstick, but he doesn't move, so she comes over and gets it. It's one of the many power plays that will take place between them. The rest is one of the great film noirs, from a studio that didn't usually make them, MGM. In fact, the studio head, Louis B. Mayer, hated it, which is always a good recommendation: He hated Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950), too. (Mayer's tastes ran to Jeanette MacDonald-Nelson Eddy operettas and the Andy Hardy series.) It's the only really memorable movie directed by Tay Garnett, so I suspect a lot of credit goes to the screenwriters, Niven Busch and Harry Ruskin, and to their source, James M. Cain's overheated novel. Cain also wrote the novels that were the basis of two other famous noirs: Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944) and Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz, 1945), so the screenwriters and the director had some powerful examples to follow.

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

Things to Come (William Cameron Menzies, 1936)

Works of fiction that pretend to depict things as they will be in a specific place and year tend to look a little foolish when that year actually comes. The years 1984 and 2001 didn't turn out to be precisely as George Orwell and Arthur C. Clarke envisioned them. But neither Orwell nor Clarke expected them to: Both were extrapolating from what they saw about the times in which they were writing. Orwell was viewing with alarm the struggle for power in 1949, and Clarke was elaborating on thoughts he had about the relationship of man, technology, and nature -- for good or ill -- in a series of stories beginning with "The Sentinel" in 1948. It's significant that both of these writers were working from a post-World War II point of view. But Things to Come starts from a very different place: England just before the second World War. H.G. Wells's 1933 The Shape of Things to Come was a meditation on a utopia founded on science, replacing religions, and a world government, replacing nationalism. The adaptation of these ideas in Wells's screenplay involves a world on the brink of war at Christmas, 1936 -- less than three years before the world actually went to war. Wells didn't have to wait long to see the ideas in the film superseded by reality. In the film the conflict lasts 40 years, and is devastating to the old order of things. There arises a kind of technotopia, which then has to battle with (and triumph over) reactionary, anti-science forces. We no longer have the kind of faith in technology to solve all problems that Wells possessed -- in fact, if the atomic outcome of World War II is any indicator, technology presents as many problems as it solves for humankind. Things to Come is muddled but fascinating: It raises the right questions while providing unsatisfactory answers. The best things in the film are the ones closest to home. For example, Ralph Richardson's performance as the dictator known as "The Boss" -- a slangy translation of Il Duce. Richardson was one of the three greatest English actors of the mid-century, but unlike Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud he rarely got a chance to show his stuff in movies. Here, his eccentric manner is the key to the role, and he plays it to the hilt. Unfortunately, Menzies, a gifted designer, wasn't much of a director, and he surrounds Richardson with inferior performers: Margaretta Scott, who had a long career once she grew accustomed to film acting, here recites her lines as if reading them for the first time and assumes poses copied from silent film vamps. For contemporary viewers, the most interesting things about the film are the set designs by Vincent Korda and the fantasias about what people will be wearing in 2036 -- which in Wells's scheme of things is the year of the first voyage around the moon. The costumes are credited to John Armstrong, René Hubert, and the Marchioness of Queensberry. (Her given name was Cathleen Mann; a portrait painter and costumer, she was married to the 11th Marquess of Queensberry from 1926 to 1946.)

|

| H.G. Wells, Pearl Argyle, and Raymond Massey on the set of Things to Come |

Monday, January 11, 2016

Days of Wine and Roses (Blake Edwards, 1962)

This melodrama about alcoholic codependency threatens to fall into didacticism, becoming a latter-day temperance lecture, but is rescued by the fine performances of Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick as Joe and Kirsten Clay. He's a ladder-climbing public relations man and she's the secretary to one of his clients; they fall in love, get married, have a child, and turn into self-destructive lushes. Eventually, with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous, and after a couple of harrowing relapses, he climbs out of it, but she refuses to admit that she has a problem that can't be solved with "will power." The film is unexpectedly bleak for one made with a solid Hollywood budget and two big stars -- both of whom received Oscar nominations -- directed by a man more famous for the Pink Panther movies and for his marriage to (and films with) Julie Andrews than for a serious problem drama. Fortunately, the film has a point to make: that alcoholism is a disease that manifests itself differently in each person who suffers from it. Joe, being a sociable type whose job has always involved drinking with clients, is the kind of person who benefits from the sense of community that AA provides. Kirsten, on the other hand, is a loner: an only child with a doting father (Charles Bickford), who when we first see her doesn't drink at all and is given to taking long walks alone on San Francisco's Fisherman's Wharf. It's Joe who introduces her to alcohol, which softens the rough edges of life -- without it, she says, everything looks "dirty." She feels comfortable denying her problem, even when it affects her marriage and her child so severely: At one point, she sets fire to their apartment in an alcoholic haze. They love each other, but she's unable to express her love for Joe unless he drinks with her. The screenplay by JP Miller is a reworking of his TV drama that appeared on Playhouse 90 in 1958, starring Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie. There is a bit too much Hollywood gloss on the film, including an Oscar-winning title song by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer, but the thoughtful core of the narrative manages to surface because everyone resisted the tendency to paste an easy resolution of the Clays' problems on the end of the film.

Sunday, January 10, 2016

Fanny and Alexander (Ingmar Bergman, 1982)

Artists' reputations often take a severe hit as time passes: No one thinks Walter Scott was as great a novelist or poet as his contemporaries did; today, he's read only by specialists, and then often grudgingly. So it's not surprising to find people who think that the directors who revolutionized filmmaking in the 1950s and '60s, like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Akira Kurosawa, are mannered and overrated. Some of Bergman's early films, I think, are: Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) is better in its Stephen Sondheim musicalized version; Wild Strawberries (1957) is a meditation on aging by someone who hasn't aged; The Seventh Seal (1957) and The Virgin Spring (1960) strive for a mythic quality that the material and the medium won't bear. But in his later career, after he had ceased to be the darling of the "art houses," he made some intensely personal films that have the warmth and humanity that he could only feint at in the early ones. Critics tend to prefer his films about women, Persona (1966) and Cries & Whispers (1972), but I find him most genuine in his exploration of childhood, especially his elegant reworking of Mozart's The Magic Flute (1975), which sees the opera through childlike eyes, and Fanny and Alexander, which works with a kind of double-vision: We know what's going on in the various sexual combinations and permutations of the Ekdahl family and their lovers, but we also have the point of view of Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and especially Alexander (Bertil Guve) to elevate them from the merely physical and sometimes sordid into the realm of mystery. If seen from the point of view of the children, this is a kind of ghost story. Alexander will carry into adulthood the experience of seeing two ghosts: one benign, his real father (Allan Edwall), and one malign, his stepfather (Jan Malmsjö). It is also a fable about two kinds of imagination: the artistic and the religious. And we know which side Bergman comes down upon rather heavily.

Saturday, January 9, 2016

Star Trek Into Darkness (J.J. Abrams, 2013)

I'm not a Trekkie. I never watched TOS* when it was first on TV, and only got hooked on TNG* when it went into re-runs. I don't speak a word of Klingon. But I can do the "Live long and prosper" hand sign, so I guess I can pass among those who aren't really hardcore. In fact, when I learned that J.J. Abrams, the rebooter of moribund franchises, was going to make his first Star Trek film (2009), I was neither appalled nor intrigued, as a real Trekkie would be. Only one of the movies featuring the cast of TOS was really very good: Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (Leonard Nimoy, 1986), aka "the one with the whales." And even then, it was the script that made William Shatner in rug and corset trying to recapture the old Capt. Kirk swagger even plausible. Fortunately, it will take a few more years before the new cast -- Chris Pine, Zachary Quinto, Zoe Saldana, Karl Urban, Simon Pegg, John Cho, and Anton Yelchin -- need their own reboot. The great charm of Star Trek has always been its ensemble work. No one watching the series either on TV or in movies really cares that much about the story. It's the interplay of characters -- the bromance of Kirk and Spock (heightened to near-homoeroticism in the Pine-Quinto version), the grumpiness of Bones McCoy, the devotion of Scotty to his engines, and so on -- that makes the creaky old sci-fi clichés come to life. Throw in some in-jokes for longtime fans, such as the Tribble in this film, and you've got a surefire hit. The remarkable thing about the cast of the Abrams films is that they so far have transcended the paint-by-numbers quality of the plots and managed to make the CGI effects secondary to the humanity. Benedict Cumberbatch is a far more terrifying Khan than Ricardo Montalban with his rubber pecs ever was. And I admit that I teared up a bit seeing Leonard Nimoy in what turned out to be his farewell cameo. No, this is not a great movie, but there is great shrewdness in its casting.

*If you're reading this entry, I assume you don't have to be told that this is Trekkiese for Star Trek: The Original Series and Star Trek: The Next Generation. But if you're reading this footnote, I guess you do.

*If you're reading this entry, I assume you don't have to be told that this is Trekkiese for Star Trek: The Original Series and Star Trek: The Next Generation. But if you're reading this footnote, I guess you do.

Friday, January 8, 2016

The Bridge on the River Kwai (David Lean, 1957)

Alec Guinness and David Lean made six features together, starting with Guinness's film debut in Great Expectations (1946). The Bridge on the River Kwai won him his only Oscar, but he seems to have been as much a good-luck charm for Lean as vice versa, since Lean miscast him rather badly in two otherwise successful films: Lawrence of Arabia (1962), in which he is rather embarrassingly non-Arab as King Feisal, and A Passage to India (1984), in which he plays Prof. Godbole with an accent that sounds more like Apu on The Simpsons than any actual Brahmin scholar. The part of Col. Nicholson in Bridge is a bit underwritten: We never really learn what the character's motives are for his eventual collaboration with the Japanese in building the bridge, and his moment of self-awareness as he says, "What have I done?" when he realizes the bridge is about to be blown up, is not adequately prepared for. But Guinness was a consummate trouper, even though he often clashed with Lean about the character, whom he wanted to be less of a stiff-upper-lip type than the director did. The movie won seven Oscars, including one for screenplay that was presented to Pierre Boulle, the author of the novel on which it was based. In fact, Boulle spoke and wrote no English; the screenplay was by Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, who were blacklisted for supposed communist ties and were judged ineligible under Academy rules. Their Oscars and their screen credit were restored posthumously in 1984. Today, Bridge looks like a well-made entertainment with some major flaws: The moral dilemma that centers on Col. Nicholson, who wants to demonstrate the superiority of the British at the expense of actually serving the Japanese cause, feels artificially created -- surely some of the officers and enlisted men under Nicholson's command had something to say about the colonel's plans. Sessue Hayakawa deserved his supporting actor nomination as Col. Saito, though the part verges on stereotype. The role of the American, Shears (William Holden), who opposes Nicholson, seems to be cooked up to provide something for a major movie star to play: Note that Holden receives top billing, and that Guinness, even though he was nominated for and won a leading actor Oscar, is billed third. The trek through the jungle by Shears, Maj. Warden (Jack Hawkins), Lt. Joyce (Geoffrey Horne), and their attractively nubile team of female bearers takes up a lot of not very involving screen time. And the demolition of the bridge and the train crossing it seems oddly anticlimactic, owing to some complications in blowing up and filming an actual full-size bridge and train. Today, of course, miniatures and special effects would be used to make the scene more exciting, but even for an actual blowing up of a bridge and a train, a sequence that had to be got right the first time, the one in Bridge is actually less successful than the one done 30 years earlier by Buster Keaton in The General (1926).

Thursday, January 7, 2016

Manhattan (Woody Allen, 1979)

Woody Allen's admiration of Ingmar Bergman's films is so well known that it becomes a gag in Manhattan when, at their first meeting, Mary (Diane Keaton) gives Isaac (Allen) a list of artists she thinks are overrated, concluding, to his astonishment, with Bergman. But Manhattan reminds me less of Bergman's films than of those of the French New Wave. Maybe it's just because I've seen several of them recently, but it strikes me that, other things being equal, Manhattan could add a seventh to Eric Rohmer's Six Moral Tales. In Claire's Knee (1970), for example, the middle-aged Jerôme (Jean-Claude Brialy) is inspired to lust by the eponymous joint of the teenage Claire (Laurence de Monaghan). In My Night at Maud's (1969), the middle-aged Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant) marries the much younger Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), and 20-year-old Haydée (Haydée Politoff) is the object of desire for both Adrien (Patrick Bauchau) and Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle) in La Collectionneuse (1967). Allen carries the premise further in Manhattan by making 42-year-old Isaac and 17-year-old Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) lovers. Is it too much to say that Allen may have found license in Rohmer's films for their somewhat shocking relationship? But Manhattan also features a familiar triangle present in several New Wave films: two men in competition for a single woman. Isaac and his friend Yale (Michael Murphy) both get involved with Mary, just as Adrien and François were involved with Haydée, and more famously, Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre) fall in love with Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) in François Truffaut's Jules and Jim (1962). Similarly, both Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur) pursue Odile (Anna Karina) in Jean-Luc Godard's Bande à Part (1964), and Paul (Jean-Claude Brialy) and Charles (Gérard Blain) contend for the affections of Florence in Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1959). Allen's celebration of New York City also reminds me strongly of the way Godard pays homage to Paris in Breathless (1960) and Chabrol has Paul give Charles a tour of the city in Les Cousins. Of course, no New Wave film was filled with wisecracks and one-liners the way Manhattan is. (Not that any Bergman film is, either.) Yet I think it's not too far-fetched to think of Allen's movie as a kind of hommage to Rohmer, Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol, et al. And if it is an hommage, it is often a handsome one, thanks to Gordon Willis's magisterial black-and-white cinematography and the wall-to-wall Gershwin soundtrack. Allen's personal life has made us more queasy about Manhattan's May-December (or at least April-September) relationship, though I'm not sure audiences ever found Isaac and Tracy a normative couple.

Wednesday, January 6, 2016

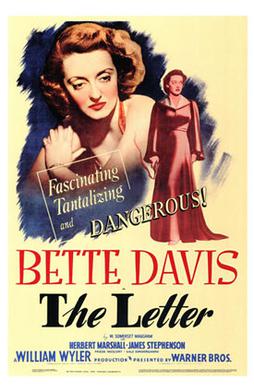

The Letter (William Wyler, 1940)

As Tony Gaudio's camera travels across the Malayan rubber plantation we hear shots being fired, and as we track closer we see Leslie Crosbie (Bette Davis), coming down her front steps with a grimly determined look on her face, firing the remaining bullets from her revolver into a man on the ground. And we sit back and relax and think, "Oh, yeah, Bette's here. This is gonna be good." Davis is one of the few stars who can almost always make us feel this way -- maybe Cary Grant or Barbara Stanwyck for me -- who else for you? And it is good, perhaps the best of the three films Davis made with William Wyler. For me, Jezebel (1938) is too steeped in the Hollywood Old South myth, and The Little Foxes (1941) too hamstrung by Lillian Hellman's dramaturgy. This one has a very fine screenplay by Howard Koch that deftly steps on and around the restrictions placed on it by the Production Code. For one thing, Leslie has to be punished for her crime, which involves not only murder but also, with the help of her lawyer, Howard Joyce (James Stephenson), suborning justice. (Joyce somehow gets off scot-free, though with an embittered conscience.) Wyler got a bad rap from the auteur critics like Andrew Sarris, who found his technical skills insufficiently personal. But we see something of Wyler's daring early in the film as Leslie is recounting her version of why she shot Geoffrey Hammond to her lawyer, her husband (Herbert Marshall), and a government official (Bruce Lester) who has been called to the scene. Wyler chooses to shoot a long segment of Leslie's story with the backs of Leslie and the three men to the camera: We don't see their faces, but only the room where the initial shooting took place. The effect, relying heavily on Davis's voice acting and Koch's script, is to place Leslie's narrative -- which as others comment rarely varies by a word -- in our minds instead of the truth. It is, for Davis, a splendidly icy and controlled performance. The major fault in the film today is in the condescension toward Asian characters typical of Hollywood in the era, though it's not as bad perhaps in 1940 as it would be after Pearl Harbor a year later. We learn that Hammond had a Eurasian wife (the Code-enforced substitute for the Chinese mistress of W. Somerset Maugham's 1927 play), and in 1940s Hollywood "Eurasian" invariable meant "sinister," especially when she's played by Gale Sondergaard. The other Asians in the film are treated as subordinates, including Joyce's Chinese law clerk, Ong Chi Seng (Victor Sen Yung), who is all smiles and passive aggressiveness. That we are expected to share in this colonialist order of things is especially apparent when Leslie is forced to deliver the payment for the incriminating letter to Mrs. Hammond, who lords it over Leslie, making her remove her shawl to bare her head and to place the money in her hands; then Mrs. Hammond drops the letter on the floor, making Leslie pick it up. If today we cheer at Mrs. Hammond's abasement of Leslie, who after all killed her husband, you can bet that 1940s audiences didn't.

Tuesday, January 5, 2016

Mission: Impossible III (J.J. Abrams, 2006)

I gave up on the Mission: Impossible series after the first two installments (Brian De Palma, 1996; John Woo, 2000) partly because they featured the world's most annoying major movie star, but also because they lacked some of the things that made the old TV series so entertaining. One of those things is intelligence, by which I mean not just spycraft but also the application of thought, rather than muscle and firepower, to problem-solving. Another is that the TV show was an ensemble affair, with Peter Graves, Martin Landau, Barbara Bain, Greg Morris, and Peter Lupus (and various successors) working together to thwart the bad guys. The films, on the other hand, were very much about Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) as a James Bond-style one-man band -- no surprise, since Cruise is the producer of the M:I movies. The other members of the Impossible Missions Force were expendable, with the exception of Ving Rhames, who has been the only other constant in the film series. I was persuaded to take another look at the series after I found myself enjoying Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Liman, 2014), which made me think that Cruise still had some valid claim to his stardom. And since J.J. Abrams has become maybe the world's most successful producer-writer-director, it also behooved me to check out the first film he directed. Abrams made a laudable effort to restore some of the ensemble work of the TV series, bringing on a team including Rhames, Billy Crudup, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Maggie Q, Simon Pegg, and Laurence Fishburne to flesh out the IMF. It doesn't quite work because Cruise still hogs the film, but there are some good bits from all of the supporting actors, and a nice contribution to IMF lore: the souped-up 3-D printer that churns out one of the famous masks the agents wind up wearing. This time it's a mask of the film's villain, Owen Davian (Philip Seymour Hoffman), and one of the best scenes in the film involves Hoffman playing Cruise playing Hoffman. But there are simply too many climaxes to the movie. I wish some of them had been cut to expand on the film's most enjoyable section, in which the team infiltrates the Vatican to kidnap Davian. I would have liked to see the planning -- the intelligence, if you will -- that went into the scheme. But I liked M:I III more than I expected. I'm told that Mission: Impossible -- Ghost Protocol (Brad Bird, 2011) and Mission: Impossible -- Rogue Nation (Christopher McQuarrie, 2015) are better, so maybe I'll eventually get around to checking them out.

Monday, January 4, 2016

Mr. & Mrs. Smith (Alfred Hitchcock, 1941)

If Hitchcock's name were not attached to this movie, would we remember it at all today? Perhaps as one of the last films of Carole Lombard -- it was the last released before her death in January 1942, though the posthumously released To Be or Not to Be (Ernst Lubitsch, 1942) was the last one she completed filming. Or perhaps as one of the lesser examples of the romantic/screwball comedy genre that flourished in the 1930s and '40s. But even hardcore Hitchcockians find it difficult to fit it into the director's canon. Hitchcock had said he wanted to work with Lombard, and when Lombard liked Norman Krasna's story and screenplay, the teaming was put into play. Lombard and Robert Montgomery play Ann and David Smith, who discover that their three-year-old marriage is invalid, owing to a legal technicality. Complications ensue, especially when David doesn't rush into remarriage as quickly as Ann likes. She kicks him out of the apartment, and then his law partner, Jeff Custer (Gene Raymond), makes a play for her affections. Lombard is very much at home in this kind of comedy, but Montgomery is surprisingly good at it too. The weak link is Raymond, who has the kind of role, the "other man" patsy, at which actors like Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth (Leo McCarey, 1937) and His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940) and John Howard in The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940) excelled. Raymond plays his part with a pinched, rather prissy manner that hardly sits well with the fact that he's supposed to have been the best fullback at the University of Alabama. In fact, the character seems to have been coded as latently gay: Witness Lombard's reaction when Ann learns that he decorated his own very tasteful apartment. Much of the film skirts around matters forbidden by the Production Code, including whether the now-unmarried Smiths should sleep together, which a director like Lubitsch or Hawks would have treated with more wit and finesse than Hitchcock does. This was only his third film made in Hollywood, and it was his first with a completely American setting; the first two, Rebecca (1940) and Foreign Correspondent (1940), were set in Europe and England. His unfamiliarity with American idiom shows up particularly in his treatment of Jeff and his parents (Philip Merivale and Lucile Watson), proper Southerners who are shocked at the suggestion that Ann has been sleeping with David. But whenever Hitchcock is working with Lombard and Montgomery, especially using Lombard's great gift for uninhibited physical comedy, the movie comes to fitful life.

Sunday, January 3, 2016

La Collectionneuse (Éric Rohmer, 1967)