A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Search This Blog

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Singin' in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952)

Egotism is accounted a sin, or at best a character flaw, but what would art, at least since the Renaissance, be without it? Imagine the history of motion pictures without the egotism of John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, or Orson Welles, not to mention countless movie stars. So it comes as a bit of a shock to find David Thomson, in his essay on Singin' in the Rain in Have You Seen ...?, making reference to "[Gene] Kelly's rather frantic ego." I do know what he means: I've always found the "Broadway Melody/Broadway Rhythm" number overlong and overdone, suggesting Kelly's attempt at being regarded as "serious" dancer, especially in the pas de quatre with Cyd Charisse, her train, and a wind machine. And its ending, with the zoom-in-close of Kelly's face, does seem a bit de trop. Thomson also hints that producer Arthur Freed may have been indulging his ego by loading the film with his and Nacio Herb Brown's catalog of songs, instead of those of better songwriters. Freed, as the head of the legendary "Freed Unit" at MGM, had won a best picture Oscar for another Gene Kelly musical based on a songwriter's catalog, An American in Paris (Vincente Minnelli, 1951), which was wall-to-wall George Gershwin. And even though Singin' in the Rain is a better movie, it might have been nicer if it had songs by Harold Arlen or Cole Porter or Rodgers and Hart. Porter at least gets plagiarized in Donald O'Connor's "Make 'em Laugh" number, the tune for which is virtually identical to that of "Be a Clown," which Porter wrote for the Freed-produced The Pirate (Vincente Minnelli, 1948). That said, the Freed-Brown songs are entirely appropriate to the era depicted: They date from such 1929 MGM musicals as The Broadway Melody (Harry Beaumont) and The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (Charles Reisner), exactly the ones parodied in Singin' in the Rain's montage of early movie musicals. My point is that egos are not enough to spoil the wonder that is Singin' in the Rain, widely regarded as one of the greatest movie musicals, and in my opinion just plain one of the great movies. Much credit goes to the expert comedy writing of Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and to Harold Rosson's cinematography. Kelly and Stanley Donen wisely did what directors of movie musicals so often fail to do: rely on long takes and full-body shots during dance numbers. As for the performers, no one in the film, and that includes Kelly and O'Connor, ever reached this peak again. Debbie Reynolds was too often betrayed into perkiness, but she is human and appealing here. Jean Hagen stole scenes from everyone and received one of the movie's two Oscar nominations -- the other was to Lennie Hayton for scoring -- but her movie career stalled and she wound up doing TV guest appearances. As for egotism, it pains me to remember that Singin' in the Rain was not nominated for the best picture Oscar winner for 1952. The winner was The Greatest Show on Earth, directed by one of the great egotists, Cecil B. DeMille. Some egotists are geniuses; others are hacks.

Friday, April 29, 2016

Body and Soul (Robert Rossen, 1947)

Body and Soul is a well-made boxing picture, but it has a historical significance as the nexus of some major careers damaged by the anti-communist hysteria that gripped the United States in the years that followed its release. After its director, Robert Rossen, pleaded the fifth amendment at his hearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951, he was blacklisted in Hollywood. The same fate befell screenwriter Abraham Polonsky after his refusal to testify before HUAC. The star, John Garfield, testified that he knew nothing about communist activity in Hollywood, but studios refused to hire him; he made his last film in 1951 and died of a heart attack the following year, only 39. Cast members Anne Revere, Lloyd Gough, Canada Lee, and Art Smith were also victims of the blacklist. The film stands as an example of the folly of HUAC witch-hunting: With all the reds and pinkos involved in its production, you might expect it to be pure propaganda, but the only leftist message it communicates is about the danger of greed. Today the only viewers who may find Body and Soul subversively anti-capitalist are those who subscribe to the "greed is good" credo enunciated by Michael Douglas's Gordon Gekko in Wall Street (Oliver Stone, 1987). Garfield plays an ambitious young boxer named Charley* Davis who falls prey to racketeers who manipulate his career, despite the warnings of his mother (Revere), his best friend, Shorty (Joseph Pevney), and his girlfriend, Peg (Lilli Palmer). The fight sequences, shot by James Wong Howe and edited by Francis Lyon and Robert Parrish, were groundbreaking in their realistic violence, winning Oscars for Lyon and Parrish. Howe, who is said to have worn rollerskates and used a hand-held camera to film the fights, was curiously unnominated, but nominations also went to Garfield and Polonsky. Palmer, unable to conceal her German accent or to eliminate traces of the sophisticated roles she usually played, is miscast as Charley's artist girlfriend. The script makes a half-hearted attempt to explain away the accent but mostly ignores it. One thing of note: The black boxer played by Lee calls Garfield's character by his first name, Charley, in their scenes together. The usual racial protocol was for African-American characters to call white ones "Mr." -- "Mr. Charley" or "Mr. Davis" -- the way Dooley Wilson's Sam always refers to Bogart's character as "Mr. Rick" in Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943). It's the earliest example of an assumed equality that I can recall in a Hollywood movie.

*A nitpicky note: The filmmakers never decided whether it was spelled "Charley" or "Charlie." It appears both ways on the posters advertising his fights, but it's "Charlie" in the inscription on a gift he gives Peg and in her letter addressed to him. I'm going with the way IMDb lists it.

*A nitpicky note: The filmmakers never decided whether it was spelled "Charley" or "Charlie." It appears both ways on the posters advertising his fights, but it's "Charlie" in the inscription on a gift he gives Peg and in her letter addressed to him. I'm going with the way IMDb lists it.

Thursday, April 28, 2016

Key Largo (John Huston, 1948)

This was the fourth and last of the films that Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, but the movie was stolen by Claire Trevor, who won a supporting actress Oscar, and by Bogart's old partner in Warner Bros. gangster movies, Edward G. Robinson. It's a little too talky and stagy, partly because it was based on a 1939 Broadway play by Maxwell Anderson, a once-admired playwright whose specialty was blank-verse dramas. Huston and co-screenwriter Richard Brooks took great liberties with the play, changing the characters and the ending, and updating the action to the postwar era, but occasionally you can hear a bit of Anderson's iambic pentameter in the dialogue. Bogart's Frank McCloud was originally called King McCloud and was a deserter from the Spanish Civil War; in the movie he's a World War II veteran, something of a hero, who comes to Key Largo to visit the father (Lionel Barrymore) and the widow (Bacall) of an army buddy who was killed in Italy. He finds them being held in the hotel they own by a group of gangsters, headed by Johnny Rocco (Robinson), a Prohibition-era mobster who is trying to sneak back into the States after being deported. As so often -- cf. Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1943) and To Have and Have Not (Howard Hawks, 1944) -- the Bogart character is called on to make a choice between taking the kind of action he has renounced and remaining neutral. Bacall's role is somewhat underwritten, and what few sparks she and Bogart strike seem to be the residue of their previous films together, especially To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep (Hawks, 1946). Having to play opposite that scene-stealing old ham Barrymore doesn't help much, either. But Trevor fully deserved her award as Rocco's moll, an alcoholic club singer known as Gaye Dawn. She has a big moment when she's forced by Rocco to sing "Moanin' Low" on the promise that he'll let her have a drink -- which he then sadistically refuses her. As usual, Robinson is terrific, and also as usual, he failed to receive the Oscar nomination he deserved and was never granted. Karl Freund's cinematography helps overcome the studio's decision not to film on location.

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2014)

I haven't read the Thomas Pynchon novel on which Anderson's film is based, but I've read enough Pynchon to know that his work is founded on a kind of literary playfulness for which there's no cinematic equivalent or even substitute. What Anderson gives us is a kind of loosey-goosey spoof of the private eye genre that works as well as it does because of brilliant casting. Joaquin Phoenix is perfect as Doc Sportello, the perpetually stoned P.I. who is trying to figure out what's going on with his ex-girlfriend Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston) while butting heads with a police detective, "Bigfoot" Bjornsen (Josh Brolin). The time is the 1970s, with Nixon as president and Reagan as California governor, and Anderson milks the period paranoia about drugs and law and order for all it's worth. The plot is as murky as a Raymond Chandler novel, which links the movie with two distinguished predecessors, The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946) and The Long Goodbye (Robert Altman, 1973), which really were based on Chandler novels. Inherent Vice isn't as good as either of those films: It's a little too long and a little too caught up in the cleverness of its spoofery. But there's always something or someone -- the cast includes Benicio Del Toro, Owen Wilson, Reese Witherspoon, and Martin Short, among others -- to watch. Brolin is a hoot as Bigfoot: With his crew cut and perpetually clenched jaw he looks for all the world like Dick Tracy -- or maybe Al Capp's parody of Dick Tracy, Fearless Fosdick.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Peppermint Frappé (Carlos Saura, 1967)

Peppermint Frappé sounds like it should be a teen beach party movie, at least until you see that it's directed by Carlos Saura and dedicated to Luis Buñuel. Then you know it's going to be a somewhat kinky story with darkly comic overtones. It opens with a middle-aged man cutting pictures of fashion models out of magazines. He's Julián (José Luis López Vázquez), a physician who runs a radiology clinic with the help of his nurse, Ana (Geraldine Chaplin), who is as quiet and conservative as he is. Then he's reunited with a boyhood friend, Pablo (Alfredo Mayo), whose life is virtually the antithesis of Julián's: Pablo has been living an adventurous life in Africa, he drives a Corvette, and he has just married the smashingly pretty and vivacious Elena, who is also played by Chaplin in a tour de force performance. Eventually, Julián's jealousy of Pablo and desire for Elena will take an increasingly predictable course, as his obsession leads to an attempt to remake Ana into Elena. Not that Saura's film is ever really predictable: As a director he has too many tricks up his sleeve, so that things always stay a little off-balance, especially when Julián invites Pablo and Elena to his weekend retreat in the country, which is next to an abandoned spa where Pablo and Julián used to play as children. Saura's use of setting is masterly in this sequence. The title refers to Pablo's favorite cocktail, a crème de menthe-based concoction served over crushed ice; it's a particularly venomous shade of green not found in nature. And yes, it plays a part in the denouement. López Vázquez and especially Chaplin give terrific performances, but the movie doesn't add up to much more than a showcase for them and Saura's skewed way of telling a story.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Death of a Cyclist (Juan Antonio Bardem, 1955)

Often cited as a landmark in Spanish cinema, Death of a Cyclist is notable for the way director Bardem (uncle of the actor Javier Bardem) manages to slip a satiric look at the Spanish upper classes past Franco's censors by tucking it into a suspense thriller. He often does this by startling jump cuts: The protagonist, Juan (Alberto Closas), looks down into the courtyard of a slum, but what we see are people attending a society wedding. The gossip Rafa (Carlos Casaravilla) angrily throws a bottle, but the window that breaks is miles away at the university where a student protest is taking place. The film is full of linkages like this, including the fact that Juan bears a striking resemblance to the man he is cuckolding, Miguel (Otello Toso). Sometimes, of course, Bardem and his co-scenarist Luis Fernando de Igoa make their satire more explicit, as when a society woman says she's supporting a charity "for poor children, or maybe for stupid children." Her distance from the objects of her charity is a comic twist on the distance that allows María (Lucia Bosé) to persuade Juan that they should leave the scene after they run down a cyclist on a lonely road at night: They are having an affair, and she doesn't want to get caught. Bardem doesn't show the actual accident or even the body of the cyclist (who is still alive after they leave the scene), leaving us to judge the couple as their guilt begins to mount -- even though they are never in any danger of being accused of the hit-and-run crime. The film continues to unfold as a saga of crime and self-punishment, made richer by Bardem's careful manipulation of point of view.

Sunday, April 24, 2016

To Have and Have Not (Howard Hawks, 1944)

Beatrice and Benedick. Rosalind and Orlando. Viola and Orsino. "Slim" and "Steve"? Is it just the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death that made me think of To Have and Have Not in terms of Shakespearean romance? Or is it that this most enjoyable of movies has a lot in common with those grand predecessors? Actually, it's all Howard Hawks's doing, with a little bit of help from screenwriters Jules Furthman and William Faulkner. Hawks had done this sort of romance before, in his comic masterpieces Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940), but leave it to Hawks to see World War II (and Ernest Hemingway's "grace under pressure" fiction) through the lens of screwball comedy. And to do it with the movies' most famous tough guy, Humphrey Bogart, and an unknown 19-year-old actress who had her name changed from Betty Perske to Lauren Bacall. And to treat it all as a semi-musical, with Hoagy Carmichael at the piano. Blood is shed and causes are espoused, but nobody takes it terribly seriously. Instead, Bogart and Bacall surf through the film on some of the best dialogue ever written, working out their fine romance as deftly as Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers ever did on the dance floor. Walter Brennan adds another memorable figure to his impressive gallery of old coots, and Marcel Dalio brings the kind of charm that might threaten to upstage lesser performers than these stars. It's certainly not a perfect film: Dolores Moran (clambering from shore to ship in heels) and Walter Szurovy are rather tediously noble as the de Bursacs. (Watch the bit when Mme. de Bursac faints and spills the chloroform and Bacall's Slim, sensing a rival for her Steve's affections, casts a stinkeye on the fallen form and intentionally fans some of the fumes in her direction.) As the Vichy police captain, Dan Seymour seems to be trying to do a Sydney Greenstreet impersonation with the worst of all French accents. And does anybody really believe that the odd company that sails off at the end to rescue a Resistance fighter from Devil's Island is going to succeed? But no matter. It's all the stuff of which legends are made.

Saturday, April 23, 2016

Queen Christina (Rouben Mamoulian, 1933)

|

| Greta Garbo and John Gilbert in Queen Christina |

Antonio: John Gilbert

Magnus: Ian Keith

Oxenstierna: Lewis Stone

Ebba: Elizabeth Young

Aage: C. Aubrey Smith

Charles: Reginald Owen

French Ambassador: Georges Renavent

Archbishop: David Torrence

General: Gustav von Seyffertitz

Innkeeper: Ferdinand Meunier

Director: Rouben Mamoulian

Screenplay: H.M. Harwood, Salka Viertel, Margaret P. Levino, S.N. Behrman

Cinematography: William H. Daniels

Production design: Edgar G. Ulmer

Film editing: Blanche Sewell

Costume design: Adrian

Music: Herbert Stothart

A year later, with the Production Code in full enforcement, this would have been a very different movie, though probably not a better one. It certainly wouldn't have shown Christina and Antonio sharing a room, not to mention a bed, in an inn. It probably wouldn't have suggested so strongly that before Antonio became her lover, Christina had a thing going with Countess Ebba, and almost certainly wouldn't have had Christina kiss Ebba on the mouth. Unfortunately, those little touches of mild naughtiness are pretty much all Queen Christina has going for it, especially if you're looking for some faint resemblance to historical fact. But maybe Garbo is enough. She certainly gives this pseudo-historical melodrama more commitment than it deserves. It was her fourth film with Gilbert, their only talkie, and their last. At least it dispels the myth that Gilbert failed to make the move into sound films because of his voice, which is perfectly fine -- the real reason was alcoholism, which made him unemployable and destroyed his health. The number of uncredited hands that worked on the screenplay, including Ben Hecht, Ernest Vajda, Claudine West, and director Rouben Mamoulian, suggests that it became a problem no one ever quite solved. Today, it is mostly remembered for the final shot of Garbo alone at the prow of a ship that is taking her away from Sweden. The story has it that Mamoulian directed her to empty her mind and think of nothing during the long closeup, to allow audiences to project their own emotions on her character.

Friday, April 22, 2016

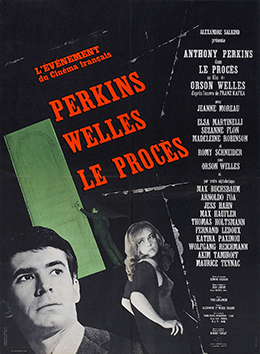

The Trial (Orson Welles, 1962)

There may be sensibilities more different from each other than those of an exiled Midwestern bon vivant and a consumptive Middle European Jew, but they rarely come together in a work of art the way they did in Orson Welles's version of Franz Kafka's The Trial. It was made in that fertile middle period of Welles's career that also saw the creation of Touch of Evil (1958) and Chimes at Midnight (1965), and it holds its own against those two landmarks in the Welles oeuvre. In the end, of course, the Wellesian sensibility dominates, the American tendency to affirmation overcoming (barely) Kafka's pessimism: Welles's Josef K. (Anthony Perkins) is rather more assertive than Kafka's protagonist. He doesn't succumb "Like a dog!" to his assailants but defies them. That said, Perkins, now carrying the indelible stamp of Norman Bates into all his roles, is superlative casting: We can believe that he's guilty -- even if we never find out what his supposed crime is -- while at the same time we sympathize with his plight. The real triumph of the film is in finding the settings in which to stage K.'s ordeal, ranging from K.'s stark, low-ceilinged apartment to bleak modern high-rise apartment and office buildings, to ornate beaux arts exteriors, to the labyrinthine courts of the law. The film was shot in the former Yugoslavia, in Italy, and in the abandoned Gare d'Orsay in Paris. Welles chose a novice, Edmond Richard, who had never shot a feature film, as his cinematographer. Richard went on to shoot Chimes at Midnight, too, as well as some of Luis Buñuel's best films, including The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). The cast includes Jeanne Moreau, Romy Schneider, Elsa Martinelli, and Akim Tamiroff, with Welles himself playing the role of Hastler, K.'s attorney, after failing to persuade Jackie Gleason or Charles Laughton to take the part. The Trial is probably longer and slower than it needs to be, and there is some inconsistency of style: The scenes involving Hastler, his mistress (Schneider), and K. are shot with more extreme closeups than the rest of the film, where the sets tend to overwhelm the human figures. And the ending, with its explosion followed by a rather wispy mushroom cloud, is a little too obviously an attempt to bring a story written during World War I into the atomic era. Some think it's a masterpiece, but I would just rank it as essential Welles -- which may or may not be the same thing.

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Alice in the Cities (Wim Wenders, 1974)

|

| Yella Rottländer and Rüdiger Vogler in Alice in the Cities |

Alice: Yella Rottländer

Lisa: Lisa Kreuzer

Director: Wim Wenders

Screenplay: Wim Wenders, Veith von Fürstenberg

Cinematography: Robby Müller

Film editing: Peter Przygodda

The Alice of Wenders's movie, played by 9-year-old Yella Rottländer, is not the plucky Victorian girl of Lewis Carroll's books, but I think they might recognize one another. Both find themselves cast adrift in a strange world in which what little guidance they have is decidedly eccentric. In Wenders's film, Alice has come to America with her mother, Lisa, who is caught up in a relationship that's not working out. Having decided to return to Germany, Alice and Lisa find themselves at a ticket counter with a German writer, Philip, who is also going home after flubbing an assignment to tour the States and write about his experiences. Flights to Germany have been canceled by an air traffic controllers' strike, but Philip helps Lisa book tickets on the same flight he's taking to Amsterdam, where they hope to make it home by ground transportation. Because Lisa speaks no English, he also helps her book a hotel room that he ends up sharing with them. And then Lisa decides to make one last effort to connect with her boyfriend, and leaves Alice with Philip, saying that she'll meet them in Amsterdam. Which she doesn't do. Philip, a cranky egotistical loner, now has a 9-year-old girl on his hands. Moreover, she hasn't lived in Germany for several years and remembers only that she has a grandmother whose name she doesn't know but who she thinks might live in Wuppertal. And off this unlikely pair goes on an oddball odyssey. What makes the film work is Wenders's lack of sentimentality, Rüdiger's depiction of Philip's gradually eroding self-centeredness, and Rottländer's entirely natural portrayal of a child in search of roots that she has never been taught she should have. It's shot in a documentary style by Robby Müller, who captures Philip's experience in an America where every place -- gas stations, fast-food joints, cheap motels -- tries to look like every other place, as well as Philip and Alice's journey through a Europe that's beginning to develop the same syndrome. Like Wenders, Philip takes photographs of urban desolation, but in the end his essential humanism prevails.

Wednesday, April 20, 2016

Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987)

Angels are usually a tiresome element in movies. I loathe the stickiness of the way they're conceived in movies like It's a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946), and even actors of the caliber of Cary Grant and Denzel Washington can't do much with playing them in films like The Bishop's Wife (Henry Koster, 1947) and its remake, The Preacher's Wife (Penny Marshall, 1996). Maybe it's because I subscribe to Rilke's dictum, Ein jeder Engel ist schrecklich -- every angel is terrible. Only a filmmaker of genius like Wim Wenders can transcend the essential cheesiness of their presence in a plot -- a cheesiness that lingers in the American remake of Wings of Desire, City of Angels (Brad Silberberg, 1988). The idea that there are angels watching over our lives, reading our thoughts, but unseen except by other angels and sometimes by children, is not a very original one. But what distinguishes the working out of this idea by Wenders and scenarists Peter Handke and Richard Reitlinger is the empathetic approach to them as beings who have been around since Creation, watching the course of humankind and unable to alter it, and occasionally so moved by what they see that they choose to give up immortality and become human. And that these angels have a specific territory to cover, in this case the city of Berlin, a nexus of human cruelty and human suffering. Even so, the concept could easily slip into banality without the blend of humor and melancholy that Wenders brings to it, without performers of the caliber of Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander as the angels Damiel and Cassiel, and without the poetic cinematography of Henri Alekan. It was also an inspired choice to cast Peter Falk as himself, an actor shooting a movie set in the Nazi era who is often stopped on the Berlin streets by people who know him as Columbo, the detective he played on television. It's also a witty touch to have Falk turn out to be an ex-angel, able to sense but not see the presence of Damiel and Cassiel. In many ways, however, the real star of the film is the city of Berlin itself -- although Wenders was prevented from shooting in the eastern sector of the city, he uses the Wall as a kind of correlative to the division between angels and humans. Almost everything works in the film, including the shifts from monochrome (the angels' point of view) to color (the humans'), the shabby little bankrupt circus whose star (Solveig Dommartin) Damiel literally falls for, and the score by Jürgen Knieper. I'm not hip enough to appreciate Nick Cave's songs, but their melancholy eccentricity is an essential part of the texture of the film.

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982)

There are movies you can watch over and over, either to savor something you hadn't particularly noticed before or in delighted anticipation of favorite parts. And then there are movies that you wish you could watch the way you did the first time you saw them, with surprise and exhilaration. I first saw E.T. in the summer of its initial release, with my wife and 8-year-old daughter in a theater in Chestnut Hill, Mass. It was an unspoiled delight, not layered over with the years' accretions of commentary and critique. I can never again see the movie that we saw that afternoon in Chestnut Hill. Watching it last night for the first time in years, I found that the best thing about it is that it brought back faint memories of the initial experience. It hasn't grown in my estimation, but on the other hand it also hasn't diminished very much. Spielberg is one of the great cinematic storytellers, particularly in his ability to narrate without words -- a gift that began to vanish from filmmaking with the arrival of sound almost 90 years ago. The opening of the film, with the scurrying, botanizing aliens and the clumsy, sinister humans who want to spy on them, is a near perfect example of showing instead of telling, and Spielberg's use of that technique is threaded throughout the movie. He also knows how to direct people, even precocious actors like Henry Thomas, Drew Barrymore, and Robert MacNaughton, who are utterly convincing in the way that movie kids rarely were before E.T. and seldom have been since. Yes, there are sequences that don't quite work, like the liberation of the frogs in the science class, and the special effects, such as the kids on the flying bicycles, look antiquated. The appearance of the resuscitated E.T., shrouded in a sheet and with a glowing heart, evoking Christian iconography, is a serious misstep. There are times when the John Williams score verges on overkill. And it undeniably helped set the film industry off in the wrong direction away from making movies for adults and toward crowd-pleasers. But all of that is part of the accretion of time. There is a timeless core to E.T. that helps it secure its place among the great movies.

Monday, April 18, 2016

Ant-Man (Peyton Reed, 2015)

|

| Michael Douglas and Paul Rudd in Ant-Man |

Dr. Hank Pym: Michael Douglas

Hope van Dyne: Evangeline Lilly

Darren Cross/Yellowjacket: Corey Stoll

Paxton: Bobby Canavale

Sam Wilson/Falcon: Anthony Mackie

Director: Peyton Reed

Screenplay: Edgar Wright, Joe Cornish, Adam McKay, Paul Rudd

Based on the comics by Stan Lee, Larry Lieber, Jack Kirby

Cinematography: Russell Carpenter

Production design: Shepherd Frankel

Film editing: Dan Lebenthal, Colby Parker Jr.

Music: Christophe Beck

The main reason to see Ant-Man is Paul Rudd, once again proving that casting is the chief thing Marvel has going for it in its efforts to capture the comic-book movie world. Like Robert Downey Jr. in the various Iron Man and Avengers movies, or Chris Pratt in his leap to superstardom in Guardians of the Galaxy (James Gunn, 2014), Rudd has precisely the right tongue-in-cheekiness to bring off a preposterous role, one that the end credits assure us he will be playing again. Rudd, whose quick wit is known from his talk show appearances, also had a hand in the screenplay, which was begun by Edgar Wright and Joe Cornish and revised and finished by Rudd and Adam McKay. For once, a comic book film is better before the CGI flash-and-dazzle take over -- the concluding portion of the film is a bit of a muddle, considering that most of the performers in the action sequences are ants. Indeed, the most impressive special effects in the movie are not the action sequences but the "youthening" of Michael Douglas, who is first seen as the much younger Hank Pym in 1989, looking much as he did in The War of the Roses (Danny DeVito, 1989), one of the films used by the special effects artists as reference. On the other hand, it has to be said here that Rudd doesn't look much older than he did 21 years ago in Clueless (Amy Heckerling, 1995).

Rififi (Jules Dassin, 1955)

The success of Rififi had a lasting effect on the "caper" or "heist" genre, which is still with us in one form or another, including the Mission: Impossible movies. Dassin's 30-minute sequence depicting the break-in and safe-cracking was hailed as a tour de force. I can't help wondering if Robert Bresson saw Rififi before he made his great 1956 film A Man Escaped, which takes a similar wordless and music-free approach to showing the preparations for Fontaine's prison break. Other than that, of course, nothing could be further from Fontaine's noble efforts to find freedom than the larcenous thuggery of Dassin's jewel thieves. Dassin knows, of course, that audiences respond positively to cleverness and skill, which is virtually all that his quartet of thieves have going for them. Tony (Jean Servais) is a brutal ex-con who beats his former mistress (Marie Sabouret) with a belt; Jo (Carl Möhner) is a swaggering, handsome guy for whom Tony took the rap for an earlier heist because Jo has a wife and child; Mario (Robert Manuel) is an easy-going ne'er-do-well; and César (Dassin under the pseudonym Perlo Vita) is a professional safe-cracker. Dassin manipulates us into thinking of these guys as heroes, if only because the gang led by Pierre Grutter (Marcel Lupovici), who wants to muscle in on their ill-gotten gains, is even worse. In the end, both sides are wiped out, but not before Jo's little boy (Dominique Maurin) is kidnapped and held for ransom. The final sequence of the film is particularly harrowing, especially to contemporary viewers used to mandated seatbelts and conscientious childproofing: A dying Tony drives the 5-year-old boy across Paris in an open convertible as the delighted kid stands on and even clambers over the seats of the speeding car. For all its unpleasantness, Rififi is as memorable as it was influential. It led to countless imitations, usually more light-hearted, including Dassin's own Topkapi (1964). It also revived Dassin's career, which had been at a standstill after he was blacklisted in Hollywood; Rififi's international success was a defiant nose-thumbing directed at HUAC's witch hunts.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

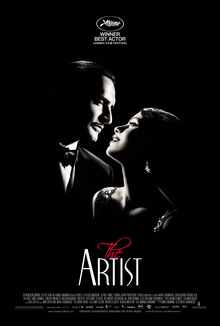

The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011)

There are two classic movies about the effect of the arrival of sound on films and the people who were silent-movie stars, Singin' in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, 1952) and Sunset Blvd. (Billy Wilder, 1950). Neither of them won the Academy Award for best picture. Coming half a century later, Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist, which did, looks oddly like an anachronism. It is certainly a tour de force: a mostly silent film with a few witty irruptions of sound in the middle when the protagonist George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), having learned that his career as a film star is ending, suddenly begins to hear sounds, even though he seems incapable of producing them himself. (At the end of the film, Valentin speaks one line, "With pleasure," revealing his French accent.) The project grew out of Hazanavicius's admiration of silent films and their directors, and it fulfilled his own desire to make one himself. The title and the central predicament of George Valentin are an acknowledgement of the fact that silent film is a distinct art form, one lost with the advent of sound. At the expense of his career, Valentin insists on preserving the art -- much as Charles Chaplin did by refusing to make City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) into talkies, long after sound had taken hold. But Valentin is no Chaplin, and his effort, an adventure story in the mode of the films that had made him famous, is a flop, coincidentally opening on the day in 1929 when the stock market crashed. Meanwhile, a younger fan and something of a protégée of his, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), becomes a huge star in talkies. From this point on, the script almost writes itself, especially if you've seen any of the versions of A Star Is Born, which is why some of us wonder how this undeniably entertaining film became such a hit and a multiple award-winner. It was nominated for 10 Academy awards and won half of them: picture, actor, director, costume design (Mark Bridges), and original score (Ludovic Bource). To my mind, Hazanavicius's screenplay is at fault for not making Valentin's supine reaction to sound entirely credible: Is it actor's ego? A fear of the new? Embarrassment at his accent? And the decision to play Valentin's suicide attempt as comedy feels like a failure of tone on the part of the writer-director. That said, the performances by Dujardin, Bejo, and the always invaluable John Goodman as the studio boss keep the movie alive. I just don't think it belongs in the company of Singin' in the Rain and Sunset Blvd.

Saturday, April 16, 2016

Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

The portrait of old age in Wild Strawberries was created by a writer-director who was 39, which is about the right time for someone to become obsessed with the past and with the portents of dreams. In the film, Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström) is 78, and by that time -- speaking as one who is nearing that age -- most of us have come to terms with the past and made sense of (or perhaps just accepted as a given) the memories and dreams that persist in haunting us. But although Bergman's film, one of the handful of breakthrough films he made in the mid-1950s, may not ring entirely true psychologically, it holds up thematically. Isak Borg is about to be commemorated with an honorary degree, one that stamps him as over the hill, and it's not surprising that it forces him to reflections about the course of his life. He is not about to go gentle into a night that he thinks of as neither good nor bad, but the journey he takes during the film -- this is an Ingmar Bergman "road movie," after all -- helps him decide to accept his life, mistakes and all. The brilliantly crabby performance by Sjöström holds it all together, even though the movie occasionally misfires: The squabbling young hitchhikers Anders (Folke Sundquist) and Viktor (Björn Bjelfenstam), who come to blows over religious faith, could almost be a self-parody of Bergman's own obsession, which would play itself out rather tiresomely in his "trilogy of faith," Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), and The Silence (1963). And the dream sequence in which Borg sees his late wife (Gertrud Fridh) and her lover (Åke Fridell) adds little to our understanding of the character. It's also possible to find the reconciliation of Borg's son (Gunnar Björnstrand) and daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin) a little too easily achieved, as if thrown in as a correlative to Borg's own affirmation. The radiant performance of Bibi Andersson in the double role of Borg's cousin Sara and the young hitchhiker who shares her name, however, almost brings the film into convincing focus. I don't think Wild Strawberries is a masterpiece, but it's certainly one of the essential films in the Bergman oeuvre.

Friday, April 15, 2016

42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933)

Julian Marsh: Warner Baxter

Dorothy Brock: Bebe Daniels

Peggy Sawyer: Ruby Keeler

Billy Lawler: Dick Powell

Abner Dillon: Guy Kibbee

Lorraine Fleming: Una Merkel

Ann Lowell: Ginger Rogers

Pat Denning: George Brent

Thomas Barry: Ned Sparks

Director: Lloyd Bacon

Screenplay: Rian James, James Seymour

Based on a novel by Bradford Ropes

Cinematography: Sol Polito

Art direction: Jack Okey

Songs: Al Dubin, Harry Warren

Costume design: Orry-Kelly

Choreography: Busby Berkeley

42nd Street is only mildly naughty, bawdy, or sporty, as the lyrics of Al Dubin and Harry Warren's title song would have it, but once Busby Berkeley takes over to stage the three production numbers at the movie's end, it is certainly gaudy. What naughtiness and bawdiness it contains would not have been there at all once the Production Code went into effect a year or so later. It's doubtful that Ginger Rogers's character would have been called "Anytime Annie" once the censors clamped down, or that anyone would say of her, "She only said 'no' once and then she didn't hear the question." Or that it would be so clear that Dorothy Brock is the mistress of foofy old moneybags Abner Dillon. Or that there would be so many crotch shots of the chorus girls, including the famous tracking shot between their legs in Berkeley's "Young and Healthy" number. Although it's often remembered as a Busby Berkeley musical, it's mostly a Lloyd Bacon movie, and while Bacon is not a name to conjure with these days, he does a splendid job of keeping the non-musical part of the film moving along satisfactorily. It helps that he has a strong lead in Warner Baxter as the tough, self-destructive stage director Julian Marsh, balanced by such skillful wisecrackers as Rogers, Una Merkel, and Ned Sparks. But it's a blessing that this archetypal backstage musical became a prime showcase for Berkeley's talents. Dick Powell's sappy tenor has long been out of fashion, and Ruby Keeler keeps anxiously glancing at her feet while she's dancing, but Berkeley's sleight-of-hand keeps our attention away from their faults. Nor does anyone really care that his famous overhead shots that turn dancers into kaleidoscope patterns would not be visible to an audience in a real theater. In the "42nd Street" number, Berkeley also introduces his characteristic dark side: Amid all the song and dance celebrating the street, we witness a near-rape and a murder. It's a dramatic twist that Berkeley would repeat with even greater effect in his masterpiece, the "Lullaby of Broadway" number from Gold Diggers of 1935. Berkeley's serious side, along with the somewhat downbeat ending showing an exhausted Julian Marsh, alone and ignored amid the hoopla, help remind us that the studio that made 42nd Street, Warner Bros., was also known for social problem movies like I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932) and the gangster classics of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, and Edward G. Robinson.

Thursday, April 14, 2016

Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1971)

|

| Dirk Bogarde in Death in Venice |

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

The Virgin Spring (Ingmar Bergman, 1960)

The Virgin Spring was probably the first Bergman film I ever saw, and it made a powerful impression that stuck with me for 50-some years. I think that's one reason why I have mixed feelings about it today. In outline, it's a simple tale based on a 13th-century Swedish ballad, in which a young girl on her way to church is raped and murdered, but from the ground where the crime took place, a spring of fresh water erupts miraculously. But watching it today I see a more complex story, full of moral ambiguities. The girl, Karin (Birgitta Pettersson), is not such a paragon as I remembered: She is spoiled and prideful, trying to sleep late and avoid the task of taking the candles to the church. She may not even be as innocent as she is thought to be: The servant, Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), who accompanies her says the reason she wants to sleep late is that she was out the previous night flirting with a boy. Karin's mother, Märeta (Birgitta Valberg), is on the one hand a religious fanatic given to self-torture, and on the other an indulgent parent unwilling to discipline her daughter. Karin's father, Töre (Max von Sydow), is divided between the Christian faith he has adopted and a furious desire to wreak revenge on the rapist-murderers. After he has killed the two men and the boy who accompanied them, he expresses remorse but also blames God for his daughter's fate. He vows to build a church on the site, and the spring gushes forth, but as a miracle it seems like a somewhat anticlimactic response to the horror that has gone before. (It's not like the site, where running water is copious, even needs another spring.) Bergman for once is working from a screenplay he didn't write: It's by Ulla Isaksson, which may be why the film is poised so ambiguously between Christian affirmation and Bergman's usual bleak alienation. It is, however, one of Bergman's most beautifully accomplished films, joining him with the cinematographer Sven Nykvist, with whom he had worked only once before (seven years earlier on Sawdust and Tinsel), and with whom he would form one of the great working partnerships in film history. In its evocation of medieval narrative and meticulous re-creation of a milieu (the production designer is P.A. Lundgren), it's superb. But as a film from one of the great modern directors it seems oddly anachronistic and insincere.

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

There comes a time in the history of any art when the pressure to do something new is exceeded by the difficulty of finding that newness. I think Persona is a good example of that problem. By the mid-1960s we had seen the great innovations in filmmaking of Buñuel, Antonioni, Resnais, and Godard, among many others. So when Ingmar Bergman chooses to open Persona with a montage of apparently random images, or chooses to dwell on images of self-immolating Buddhist monks during the Vietnam war or children being rounded up by the Gestapo, or to repeat an entire scene, or to resort to a kind of Verfremdungseffekt by showing the director and his crew filming the scenes we're watching, we can mutter to ourselves, "Seen that one before." The remarkable thing is that none of this apparently derivative film and narrative technique seriously weakens the movie, which is one of Bergman's best. Even though we can dismiss the killing of the sheep in the opening montage as a kind of homage to (or borrowing from) Buñuel's Un Chien Andalou (1929), or point at the opening of Resnais's Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) as another example of such a montage, or cite Godard's political engagement as a precursor of Bergman's use of Vietnam and the Holocaust in his film, none of that really matters. Persona stands firm on its own, largely because of the phenomenal performances of Bibi Andersson as Alma and Liv Ullmann as Elisabet, and the extraordinary art of Sven Nykvist's black-and-white cinematography. The only other film in Bergman's opus that seriously challenges it for primacy, I think, is Cries and Whispers (1972), and that largely because Bergman had by that time realized that innovation could be a dead end and that concentrating on story and character without cinematic tricks was all that was needed to make a successful film. The core of Persona lies in the fascinating, ever-shifting relationship between the mute Elisabet and the garrulous Alma, and we don't even need the sequence in which the images of the two actresses merge into one to get the point. It's sometimes said that the film works because Andersson and Ullmann look so much alike, but they really don't. Andersson has a kind of conventional prettiness: As I noted in my entry on The Devil's Eye (Bergman, 1960), she could almost pass as the heroine of a 1960s American sitcom like Donna Reed or Elizabeth Montgomery. Ullmann has a stronger face: a more determined gaze, powerful cheekbones, a fuller, more sensuous mouth. The two women could not have exchanged roles in the film without a serious disruption in their relationship: Even though she's three years younger than Andersson, Ullman has to play the mature, successful actress, and Andersson the eager young nurse. What gives their relationship in the film its marvelous tension is the sense that Alma is imbibing, in an almost vampiric way, the strength that Elisabet possessed before her onstage breakdown. Part of me wishes that Bergman had had the conviction to tell the two women's stories without the narrative gimmicks, but another part tells me that Persona has to be judged for what it is, and that it's one of the great films.

Links:

Bibi Andersson,

Ingmar Bergman,

Liv Ullmann,

Persona,

Sven Nykvist

Monday, April 11, 2016

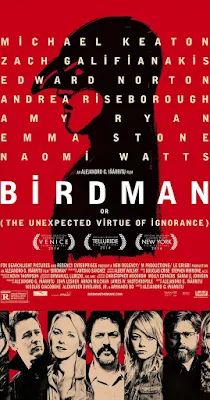

Boyhood (Richard Linklater, 2014)

Academy voters had essentially two choices for best picture of 2014, not that there weren't six other nominees, two of them, The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson) and Whiplash (Damien Chazelle), quite worthy of the honor. But Birdman (Alejandro González Iñárritu) and Boyhood were the front-runners, in large part because they took great risks. In addition to an often surreal approach to its subject matter, Birdman was filmed to give the illusion that most of it was one continuous take -- even though the narrative was not necessarily continuous. And Boyhood was filmed over the course of 12 years, as its protagonist, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), went from the age of 6 to 18 years old. Faced with two such groundbreaking but inimitable films, the Academy chose poorly: It went for the flashy technique of Birdman instead of the profoundly revealing story of the pressures a child faces in the process of growing up. But it's not just Mason's story, it's also that of his mother (Patricia Arquette), his sister (Lorelei Linklater), and his father (Ethan Hawke). Arquette deservedly won a supporting actress Oscar, but Hawke (who was nominated) also demonstrated the remarkable ability to adapt his persona over the extended filming time. The divorced parents face pressures, too: the mother the more immediate one of becoming a single parent and then making disastrously wrong choices as she remarries, the father the long-term one of remaining a presence in the lives of his children. He seems to have it easier than his ex-wife does, but every time Hawke re-appears in the film, he beautifully communicates the sense of having lost something precious. Like his son, he grows, shedding his fecklessness and irresponsibility, just as Mason learns to sift through the continuous barrage of advice from adults and find the wisdom to become his own person. I don't know of any film that so tenderly presents what the quotidian is like, without resorting to melodramatic crisis at its turning points. The only other films I can even compare it to are François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) and Satyajit Ray's Aparajito (1956), which take place in much harsher milieus than the Texas towns and cities in which Linklater sets Boyhood. But even though that world is milder and more familiar than the places in France and India where Truffaut and Ray set their films, Boyhood reveals how the world shapes us -- or as Linklater puts it at the end of his film, "the moment seizes us" -- as well as those films do. I think it's a treasure that belongs in their august company.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

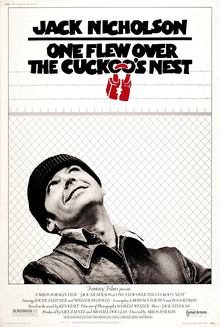

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (Milos Forman, 1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest is beginning to show its age, as any 41-year-old movie must. It no longer exhibits the freshness that won it acclaim as a masterpiece and raked in the five "major" Academy Awards: picture, director, actor, actress, and screenplay -- only the second picture in history to do that: The first was It Happened One Night (Frank Capra, 1934), and only one other picture, The Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991), has subsequently accomplished that feat. Today, however, One Flew has the look of a skillfully directed but somewhat predictable melodrama; its tragic edge has been blunted by familiarity. In treating the material, director Forman goes for straightforward storytelling, without showing us something new or personal as an auteur. And as time has passed, some of the elements of the source, Ken Kesey's novel, that screenwriters Laurence Hauben and Bo Goldman took pains to mitigate -- namely the countercultural glibness and antifeminism -- have begun to show through. It's harder today to wholeheartedly cheer on the raw, anarchic antiauthoritarianism of McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) or to accept as a given the unmitigated villainy of Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher). We want our protagonists and antagonists to be a little more complicated than the film allows them to be. There are still many who think it a great film, but if it is, I think it's largely because it's the perfect showcase for a great talent -- Nicholson's -- supported by an extraordinary ensemble that includes a shockingly young-looking Danny DeVito, Scatman Crothers, Sidney Lassick, Christopher Lloyd, Will Sampson, and a touchingly vulnerable Brad Dourif.

Saturday, April 9, 2016

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

|

| Uma Thurman and John Travolta in Pulp Fiction |

Honey Bunny: Amanda Plummer

Vincent Vega: John Travolta

Jules Winnfield: Samuel L. Jackson

Butch Coolidge: Bruce Willis

Marsellus Wallace: Ving Rhames

Mia Wallace: Uma Thurman

Capt. Koons: Christopher Walken

Fabienne: Maria de Medeiros

Winston Wolfe: Harvey Keitel

Brett: Frank Whaley

Jody: Rosanna Arquette

Lance: Eric Stoltz

Director: Quentin Tarantino

Screenplay: Quentin Tarantino, Roger Avary

Cinematography: Andrzej Sekula

Production design: David Wasco

Film editing: Sally Menke

Watching Pulp Fiction again -- I don't know how many times I've seen it but it feels like a lot -- I'm struck by how much the film is about language. In a way that's appropriate, given that it was nominated for seven Oscars but won only for the screenplay by Tarantino and Roger Avary. And certainly language comes to the fore in the way the film tramples on taboos like the f-word and the n-word, which are repeated so often that you're numbed to the expected shock. And then there's the great biblical tirade by Jules, extrapolated from a passage in Ezekiel and repeated three times to make sure we get the point that Jules is some kind of prophet. And of course there's the familiar pronouncement by Vincent that the French call a quarter-pounder with cheese a Royale with cheese. But throughout the film characters encounter semantic problems, as when Jules asks Brett what country he's from. The puzzled Brett asks, "What?" thereby provoking Jules's response, "'What' ain't no country I've ever heard of. They speak English in What?" Or when Esmeralda (Angela Jones) asks Butch what his name means, and Butch replies, "I'm American, honey. Our names don't mean shit." Or when Pumpkin calls out, "Garçon! Coffee!" and the waitress (Laura Lovelace) corrects him: "'Garçon' means boy." Pumpkin and Honey Bunny have even decided to give up robbing liquor stores because they're owned by "too many foreigners [who] don't speak fucking English." For Pulp Fiction's characters language is a means of establishing dominance, as when Winston Wolfe refuses Vincent's request to say "please" when he's giving orders. It's also a way of establishing intimacy: When Vincent brings Mia home after she has overdosed, she finally tells him the silly joke -- a pun on catch up/ketchup -- that she refused to tell him earlier. So maybe Pulp Fiction isn't exactly about language -- it's also about violence and God and a lot of other things -- but I don't know of many other recent films that are so memorable because of it.

Friday, April 8, 2016

The General (Buster Keaton and Clyde Bruckman, 1926)

The Civil War had been over for 60 years when The General was made, and from the tone of it you might think the South had won. That was, however, the usual attitude in Hollywood, and would remain so for perhaps another 40 years. The reason usually given for Hollywood's avoidance of treating the Southern states as what they really were -- i.e., racist traitors -- is a fear of losing the considerable market that the former states of the Confederacy constituted. So The General seems biased toward treating the Confederacy as a genteel homeland full of honorable, self-sacrificing heroes. There's no shying away from waving the Confederate battle flag as there would be today, and the strains of "Dixie" are used to stirring effect even in the score composed for the restored version seen on TCM -- as they would have been in any theatrical showing in the year of its release. If all this sounds like a curious quibble about one of the great silent comedies, now regarded as Buster Keaton's masterpiece (or at least one of them), so be it. But I was born a Southerner and raised to take such sentimentality about the region's past as a matter of course, in large part because Hollywood encouraged it. Now that I know better, I don't think it hurts to quibble about such things, especially when the political air is currently filled with legislated tolerance of discrimination, much (but not all) of it emanating from the states of the Old South. But let's lighten up: The General is a great film despite its wrongheaded view of history, and Keaton is one of the masters of the medium. Every time I watch it I see something new: This time, for example, I was taken with the sequence near the start of the film when Johnnie Gray (Keaton) arrives home with the first of his two loves (his engine, the General) and goes to see the other love, Annabelle Lee (Marion Mack). He is trailed to her house by two small boys, following in single file, and unknown to them Annabelle joins the little procession. Arriving at her door, he knocks, only to notice with a double-take that she's right behind him. They enter her living room, with the two boys following and seating themselves on the couch to observe. Johnnie sees them, pretends that he's leaving, goes to the door, ushers them out first, and then closes the door behind them. It's a simple gag routine of no importance to the plot (we never see the boys again), but it's executed with such straight-faced precision, as if it were being performed to a metronomic beat, that it becomes a small delight. Henri Bergson's theory of comedy is as unreadable as most theories of comedy are, but he makes a point that some things are funny because they show human beings behaving mechanically. Human beings are elastic and unpredictable, and when they turn inelastic and predictable, they can become funny. Almost everything in The General is done with this straight-faced precision, so that we laugh even when Keaton departs from it. Marion Mack proves herself a game performer here, subjected to all sorts of torments from being caught in a bear trap to being tied in a sack and flung into a boxcar to being drenched with water. Throughout it all she remains a ditz, and we often want to throttle her because of it. So when Keaton gives in to the exasperation we are all feeling with her, he does start to throttle her -- and then, endearingly, changes his mind and kisses her.

Thursday, April 7, 2016

Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2014)

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

Radio Days (Woody Allen, 1987)

Woody Allen's warmest and maybe most irresistible film has none of the neurotic obsession gags or existentialist angst shtick that are so often associated with his work. It's a simple piece about the nostalgia that old songs evoke in us -- in Allen's case, reminiscences of the days when radio was the dominant, almost ubiquitous medium in people's lives, before television held people captive in their living rooms or the internet addicted them to the little screens of their cell phones or tablets. Specifically, it's Allen's childhood as seen through the eyes of young Joe (Seth Green) and his parents (Julie Kavner and Michael Tucker) and extended family. It's also, secondarily, a tribute to many of the actors who have enlivened Allen's films, with smaller roles and cameos filled by Dianne Wiest, Mia Farrow, Danny Aiello, Jeff Daniels, Tony Roberts, Diane Keaton, and many others. Production designer Santo Loquasto deservedly received an Oscar nomination for his re-creation of Queens and Manhattan in the late 1930s and early 1940s, but honors should go to the luminous cinematography of Carlo Di Palma, too. The soundtrack, supervised by Dick Hyman, ranges from such true classics as Kurt Weill's "September Song" and Duke Ellington's "Take the 'A' Train" to novelty pop of the period like "Mairzy Doats" and "Pistol Packin' Mama." As one born B.T. (Before Television), I can really dig it.

Tuesday, April 5, 2016

High and Low (Akira Kurosawa, 1963)

High and Low begins surprisingly, considering that Kurosawa is known as a master director of action, with a long static sequence that takes place in one set: the living room of the home of Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune), an executive with a company called National Shoe. The sequence, almost like a filmed play, depicts Gondo's meeting with the other executives of the company, who are trying to take it over, believing that the "Old Man" who runs it is out of touch with the shoe market. Gondo, however, thinks the company should focus on well-made, stylish shoes rather than the flimsy but fashionable ones the others are promoting. After the others have gone, we see that Gondo has his own plan to take over the company with a leveraged buyout -- he has mortgaged everything he has, included the opulent modern house in which the scene takes place. But suddenly he receives word that his son has been kidnapped and the ransom will take every cent that he has. Naturally, he plans to give in to the kidnappers' demands -- until he learns that they have mistakenly kidnapped the wrong child: the son of his chauffeur, Aoki (Yutaka Sada). Should he go through with his plans to ransom the boy, even though it will wipe him out? Enter the police, under the leadership of Chief Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai), and the scene becomes a complicated moral dilemma. Thus far, Kurosawa has kept things stagey, posing the group of detectives, Gondo, his wife (Kyoko Kagawa), his secretary (Tatsuya Mihashi), and the chauffeur in various permutations and combinations on the Tohoscope widescreen. But once a decision is reached -- to pay the ransom and pursue the kidnappers -- Kurosawa breaks free from the confinement of Gondo's house and gives us a thrilling manhunt, the more thrilling because of the claustrophobic opening segment. The original title in Japanese can mean "heaven and hell" as well as "high and low," and once we move away from Gondo's living room we see that his house sits high on a hill overlooking the slums where the kidnapper (Tsutomu Yamazaki) lives, and from which he can peer into Gondo's house through binoculars. We return to the police procedural world of Stray Dog (Kurosawa, 1949), where sweaty detectives track the kidnapper through busy nightclubs and the haunts of drug addicts, and Kurosawa's cameras -- under the direction of Asakazu Nakai and Takao Saito -- give us every sordid glimpse. It's a skillful thriller, based on one of Evan Hunter's novels written under the "Ed McBain" pseudonym, done with a masterly hand. And while it's not one of Kurosawa's greater films, it has unexpected moral depth, enhanced by fine performances, including a restrained one by Mifune -- this time, the freakout scene goes to Yamazaki's kidnapper.

Monday, April 4, 2016

Stray Dog (Akira Kurosawa, 1949)

Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura, who starred in Seven Samurai, appeared together five years earlier in this noir detective story. In a crowded bus on a sweltering day, Murakami (Mifune), a rookie homicide detective, has his gun stolen by a pickpocket. He gives chase but loses the thief, and shamefacedly has to report it to headquarters. To make matters worse, he soon discovers that the gun has been used in a robbery, wounding the victim. He begins a dogged search for the gun. In an extended sequence Kurosawa's depiction of police work takes us into the lower depths of post-war Tokyo as Murakami follows a lead that suggests the gun may have been sold on the underground gun market. Murakami's guilt becomes more intense after ballistics work reveals that his gun had been used in a robbery homicide and he witnesses the grief of the victim's husband. But he's teamed up with a veteran detective, Sato (Shimura), who persuades Murakami not to quit the force and accompanies him in an effort to retrieve the weapon. It's not only a well-made thriller but also a complex portrait of the lingering effects of the war on the Japanese populace, peering into sleazy nightclubs and cobbled-together hovels. Mifune and Shimura are a fine team, with the former far more restrained than he was in Seven Samurai and the latter adding a deeper note of warmth to the quiet integrity he demonstrated as the leader of the samurai band. Keiko Awaji plays the nightclub dancer who knows the hangouts of the gunman (Isao Kimura, who played the naive young samurai Katsushiro in the later film) but is reluctant to give him up. A vivid supporting cast and Asakazu Nakai's atmospheric cinematography make this more than just a skillful reworking of an American genre movie.

Sunday, April 3, 2016

Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa,1954)

It's a truism -- one that I've often echoed -- that silent movies and talkies constitute two distinct artistic media, and to judge the one by the standards of the other is an error. But it's almost impossible to watch films made by older directors, especially those who came of age when silent films were being made, without noticing the efforts they make to tell their stories without speech. It's true of John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Howard Hawks, even though they, especially Hawks, became masters of dialogue in their films. And it's true of Kurosawa, who although he didn't begin his career in films until 1936 and directed his first one in 1943, was born in 1910 and grew up with silent movies. I think it helped him learn the universals of storytelling that are independent of language, so that he became the most popular of all Japanese filmmakers. Others rank the work of Ozu or Mizoguchi more highly, but Kurosawa's films manage to transcend the limitations of subtitles more easily. Of none of his films is this more true than Seven Samurai, which is also generally regarded, even by those with reservations about Kurosawa's work, as his masterpiece. That's not a word I use lightly, but having sat enthralled through the uncut version, three hours and 27 minutes long, last night, I'm willing to endorse it. It's an exhilarating film, with none of the longueurs that epics -- I'm thinking of Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) and Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1962) -- so easily fall into. I don't know of any action film with as many vividly drawn characters, and that's largely because Kurosawa takes the time to delineate each one. It's also a film about its milieu, 16th-century Japan, although as its American imitation, The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960), shows, there's a universality about the antagonism between fighters and farmers. Kurosawa captures this particularly well in the character of Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune), the would-be samurai who reveals in mid-film that he was raised as a farmer and carried both a kind of self-hate for his class along with a hatred for the arrogant treatment of farmers by samurai. Mifune's show-off performance is terrific, but the film really belongs to Takashi Shimura, who radiates stillness and wisdom as Kambei Shimada, the leader of the seven. There are clichés to be found, such as the fated romance of the young samurai trainee Katsushiro (Isao Kimura) and the farmer's daughter Shino (Keiko Tsushima), but like the best clichés, they ring true. Seven Samurai earned two Oscar nominations, for So Matsuyama's art direction and Kohei Ezaki's costumes, but won neither. Overlooking Kurosawa's direction, Shimura's performance, and Asakazu Nakai's cinematography is unforgivable, if exactly what one expects from the Academy.

Saturday, April 2, 2016

No Regrets for Our Youth (Akira Kurosawa, 1946)

| Setsuko Hara in No Regrets for Our Youth |

Friday, April 1, 2016

Funny Face (Stanley Donen, 1957)

Is there anything better than Astaire singing Gershwin? And in Funny Face he sings five Gershwin songs with his impeccable phrasing and musicianship, which in itself would be enough to make this one of the great film musicals. Okay, maybe it's not up there with the best of the Astaire-Rogers films or The Band Wagon (Vincente Minnelli, 1953), but it's close enough. And he dances, too, with the same grace and vitality at the age of 58 as when he was much, much younger, especially in his great solo performance of "Let's Kiss and Make Up" and his duet with Kay Thompson on "Clap Yo' Hands." So Audrey Hepburn isn't in the same league as Ginger Rogers or Cyd Charisse as a dance partner, but she had studied ballet when she was much younger and her solo number parodying modern dance moves is one of the film's highlights. As a singer, she's a good actress, by which I mean that her big solo number, "How Long Has This Been Going On?", is memorable because of the way she sells the concept of innocence awakening to ecstasy, greatly aided by a big yellow hat and Ray June's gorgeous color cinematography. It's clear that she had a small, untrained singing voice, which is why Marni Nixon had to be called in to dub her in My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964), a role that makes demands she probably couldn't have met vocally. There are those who are bothered by the nearly 30-year age discrepancy between Astaire and Hepburn, but she spent much of her career playing opposite much older men like Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, and Cary Grant -- in her prime in the 1950s and early '60s, there were very few leading men her age who could match her star power. Some critics also object to the film's mockery of French intellectuals -- Pauline Kael calls the lecherous philosopher played by Michel Auclair "a sour idea" -- but that's probably asking too much of the conventions of romantic comedy. The screenplay is by Leonard Gershe, but the real heroes of the film are Astaire, Hepburn, Thompson, June, Roger Edens in his dual role as producer and composer, costume designers Edith Head and Hubert de Givenchy, photographer Richard Avedon as "visual consultant," and most of all Stanley Donen, who not only directed but shared choreography duties with Astaire and Eugene Loring.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_poster.jpg)