A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Tuesday, June 6, 2017

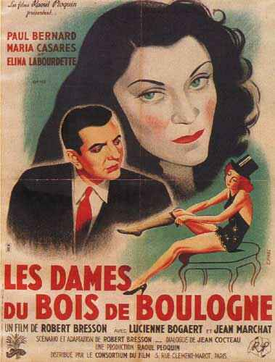

Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (Robert Bresson, 1945)

I doubt that I would have recognized Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne as a film by Robert Bresson if I hadn't already known it was the second feature film of his career. Its milieu, the haute bourgeoisie, is far removed from the priests, peasants, pickpockets, and prison escapees of his great later films, which also relied on non-professional actors instead of the established professionals of this film. There is even a rather lush score by Jean-Jacques Grünewald, instead of the reliance on ambient sound characteristic of the more familiar period. Clearly, something happened to Bresson's aesthetic in the six years that separate Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne from Diary of a Country Priest (1951). And yet there's something in the restraint with which Bresson films this updating of a story by Denis Diderot and in the clarity of moral vision with which he imbues it that keeps it "Bressonian." Diderot's 18th-century story is of an age with Choderlos de Laclos's Les Liasons Dangereuses, which has been filmed half a dozen times, including versions updated to the 20th century by Roger Vadim (1959) and Roger Kumble (Cruel Intentions, 1999). Diderot's and Laclos's stories both turn on the failure of the best-laid plans of vengeful lovers: Erotic obsession becomes a two-edged sword. With the help of Jean Cocteau's dialogue and well-judged performances by Maria Casares, Paul Bernard, and Elina Labourdette, Bresson maintains the tension of withheld revelations throughout the narrative in which Hélène (Casares) manipulates her former lover Jean (Bernard) into marrying Agnès (Labourdette), who is not the "impeccable" woman Hélène deceives Jean into believing her to be. The dénouement, in which Jean, having learned the truth, finds himself trapped inside his own automobile, is brilliantly staged. And even the bittersweet sort-of-happy ending feels right, if only because Bresson has revealed the inescapable cruelty of the milieu in which it takes place. I suspect that even if Bresson had gone on in this vein, rather than carving out for himself his unique place in film history, he would still be regarded as an important filmmaker.

Links:

Elina Labourdette,

Jean Cocteau,

Jean-Jacques Grünewald,

Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne,

Maria Casares,

Paul Bernard,

Robert Bresson

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)