A blog formerly known as Bookishness / By Charles Matthews

"Dazzled by so many and such marvelous inventions, the people of Macondo ... became indignant over the living images that the prosperous merchant Bruno Crespi projected in the theater with the lion-head ticket windows, for a character who had died and was buried in one film and for whose misfortune tears had been shed would reappear alive and transformed into an Arab in the next one. The audience, who had paid two cents apiece to share the difficulties of the actors, would not tolerate that outlandish fraud and they broke up the seats. The mayor, at the urging of Bruno Crespi, explained in a proclamation that the cinema was a machine of illusions that did not merit the emotional outbursts of the audience. With that discouraging explanation many ... decided not to return to the movies, considering that they already had too many troubles of their own to weep over the acted-out misfortunes of imaginary beings."--Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Friday, March 3, 2017

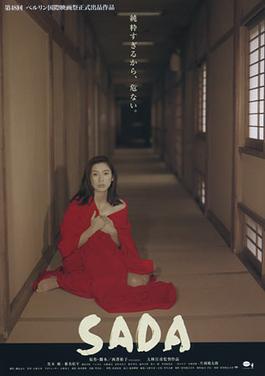

Sada (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1998)

Having seen House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977) and In the Realm of the Senses (Nagisa Oshima, 1976), I had to see what the director of the former -- a brightly colored, over-the-top horror film, set to a bubble-gum pop soundtrack, about a gaggle of Japanese schoolgirls who find themselves in a haunted house and proceed to die in various colorful and inventive ways -- would do with the latter -- a sexually explicit account, with full nudity and unsimulated copulation, of the crime of Sada Abe, who in 1936 killed her lover, Kichizo Ishido, carved their names on his body, and cut off his genitals, carrying them around with her until she was arrested. The story of Sada has been the subject of numerous books and at least five movies in Japan, after her trial -- which resulted in five years in prison -- set off a nationwide sensation, turning her into a kind of folk hero. The result is a curiously show-offy film that Obayashi fills with all manner of tricks: switches from color to black-and-white, characters breaking the fourth wall, eccentric cuts and startling shifts of tone, and deliberate violations of cinematic convention. In one scene, Sada (Hitomi Kuroki) and her lover, whose name has been changed to Tatsuzo (Tsurutaro Kataoka) in the film, are walking along the street together. The camera follows Tatsuzo from right to left as he speaks, then cuts to Sada as she replies. Film convention calls for a shot followed by a reverse shot, in which we see first Tatsuzo and then Sada from different angles. Instead, Obayashi cuts to Sada, filmed from the same angle and still traveling from right to left, as if she has somehow physically replaced Tatsuzo. This and similar impossible cuts and angles in the film are probably meant to suggest Sada's identification with her lover. Tone shifts mark the film from the beginning: It opens with 14-year-old Sada's rape by a teenage boy, a harrowing scene that is nevertheless somehow played as if it were comic, just as later Sada's work as a prostitute shifts into comic mode with speeded-up action and cuts to a voyeur watching from his hiding place, and a fight with Tatsuzo's wife becomes almost slapstick. Obayashi seems determined to avoid anything that smacks of melodrama or sentimentality. but not always successfully. The screenplay, by Yuko Nishizawa, tries to add depth to Sada's story by inventing a young medical student, Okada (Kippei Shina), who tends to her after her rape. He becomes a symbol of Sada's loss of anything but physical love when he is forced to part from her: He gives her his scalpel and has her mime cutting out his heart and taking it with her -- an obvious foreshadowing of her actual use of the scalpel on Tatsuzo. Sada spends much of the film hoping to be reunited with Okada, only to find that he has leprosy and has been sent to an island on the Inland Sea for quarantine. The film ends with a shot of an elderly woman looking out across the sea to the island. In contrast to Oshima's In the Realm of the Senses, Obayashi's film avoids nudity, but this only serves to add another layer of distance between the viewer and Sada. Kuroki, a beautiful young actress, does what she can with the role, but the constant camera tricks and the limitations imposed by the script never let us get more than a superficial glimpse of what drove Sada Abe to act as she did.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)