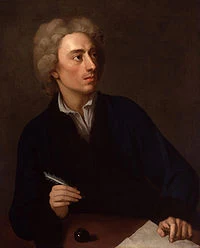

If Shakespeare, Chaucer and Milton are the Big Three of English poetry, then Alexander Pope is a strong contender for fourth place. Not that I was ever able to convince college students of that when I was teaching them. And you may be skeptical, too, if all the Pope you ever read was in a survey course, and that consisted of The Rape of the Lock and maybe some excerpts from An Essay on Criticism and Essay on Man. Brilliant as they are, they don't suggest the full range of Pope's artistry.From The Dunciad

(Book I, lines 55-78)

Here she beholds the Chaos dark and deep,

Where nameless Somethings in their causes sleep,

'Till genial Jacob, or a warm Third day,

Call forth each mass, a Poem, or a Play:

How hints, like spawn, scarce quick in embryo lie,

How new-born nonsense first is taught to cry,

Maggots half-form'd in rhyme exactly meet,

And learn to crawl upon poetic feet.

Here one poor word an hundred clenches makes,

And ductile dulness new meanders takes;

There motley Images her fancy strike,

Figures ill pair'd, and Similies unlike.

She sees a Mob of Metaphors advance,

Pleas'd with the madness of the mazy dance:

How Tragedy and Comedy embrace;

How Farce and Epic get a jumbled race;

How Time himself stands still at her command,

Realms shift their place, and Ocean turns to land.

Here gay Description Ægypt glads with show'rs,

Or gives to Zembla fruits, to Barca flow'rs;

Glitt'ring with ice here hoary hills are seen,

There painted vallies of eternal green,

In cold December fragrant chaplets blow,

And heavy harvests nod beneath the snow.

(Book IV, lines 397-457)

Then thick as Locusts black'ning all the ground,

A tribe, with weeds and shells fantastic crown'd,

Each with some wond'rous gift approached the Pow'r,

A Nest, a Toad, a Fungus, or a Flow'r,

But far the foremost, two, with earnest zeal,

And aspect ardent to the Throne appeal.

The first thus open'd: "Hear thy suppliant's call,

Great Queen, and common Mother of us all!

Fair from its humble bed I rear'd this Flow'r,

Suckled, and chear'd, with air, and sun, and show'r,

Soft on the paper ruff its leaves I spread,

Bright with the gilded button tipt its head,

Then thron'd in glass, and nam'd it CAROLINE:

Each Maid cry'd, charming! and each Youth, divine!

Did Nature's pencil ever blend such rays,

Such vary'd light in one promiscuous blaze?

Now prostrate! dead! behold that Caroline:

No Maid cries, charming! and no Youth, divine!

And lo the wretch! whose vile, whose insect lust

Lay'd the gay daughter of the Spring in dust.

Oh punish him, or to th' Elysian shades

Dismiss my soul, where no Carnation fades."

He ceas'd, and wept. With innocence of mein,

Th' Accus'd stood forth, and thus address'd the Queen.

"Of all th' enameled race, whose silv'ry wing

Waves to the tepid Zephyrs of the spring,

Or swims along the fluid atmosphere,

Once brightest shin'd this child of Heat and Air.

I saw, and started from its vernal bow'r

The rising game, and chac'd from flow'r to flow'r.

It fled, I follow'd; now in hope, now pain;

It stopt, I stopt; it mov'd, I mov'd again.

At last it fix'd, 'twas on what plant it pleas'd,

And where it fix'd, the beauteous bird I seiz'd:

Rose or Carnation was below my care;

I meddle, Goddess! only in my sphere.

I tell the naked fact without disguise,

And, to excuse it, need but shew the prize;

Whose spoils this paper offers to your eye,

Fair ev'n in death! this peerless Butterfly."

"My sons! (she answer'd) both have done your parts:

Life happy both, and long promote our arts.

But hear a Mother, when she recommends

To your fraternal care, our sleeping friends.

The common Soul, of Heav'n's more frugal make,

Serves but to keep fools pert, and knaves awake:

A drowsy Watchman, that just gives a knock,

And breaks our rest, to tell us what's a clock.

Yet by some object ev'ry brain is stirr'd;

The dull may waken to a Humming-bird;

The most recluse, discreetly open'd find

Congenial matter in the Cockle-kind;

The mind, in Metaphysics at a loss,

May wander in a wilderness of Moss;

The head that turns at super-lunar things,

Poiz'd with a tail, may steer on Wilkins' wings.

"O! would the Sons of Men once think their Eyes

And Reason giv'n them but to study Flies?

See Nature in some partial narrow shape,

And let the Author of the Whole escape:

Learn but to trifle; or, who most observe,

To wonder at their Maker, not to serve."

(Book IV, lines 627-656)

In vain, in vain, -- the all-composing Hour

Resistless falls: The Muse obeys the Pow'r.

She comes! she comes! the sable Throne behold

Of Night Primæval, and of Chaos old!

Before her, Fancy's gilded clouds decay,

And all its varying Rain-bows die away.

Wit shoots in vain its momentary fires,

The meteor drops, and in a flash expires.

As one by one, at dread Medea's srain,

The sick'ning stars fade off th' ethereal plain;

As Argus' eyes by Hermes' wand opprest,

Clos'd one by one to everlasting rest;

Thus at her felt approach, and secret might,

Art after Art goes out, and all is Night.

See skulking Truth to her old Cavern fled,

Mountains of Casuistry heap'd o'er her head!

Philosophy, that lean'd on Heav'n before,

Shrinks to her second cause, and is no more.

Physic of Metaphysic begs defence,

And Metaphysic calls for aid on Sense!

See Mystery to Mathematics fly!

In vain! they gaze, turn giddy, rave, and die.

Religion blushing veils her sacred fires,

And unawares Morality expires.

Nor public Flame, nor private, dares to shine;

Not human Spark is left, nor Glimpse divine!

Lo! thy dread Empire, CHAOS! is restor'd;

Light dies before thy uncreating word;

Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;

And Universal Darkness buries All.

--Alexander Pope

I think one of the chief stumbling blocks to an appreciation of Pope may be the heroic couplet. Pope wrote almost exclusively in this verse form, and if you're not attuned to its subtleties, it may sound to you like a typewriter (if you're old enough to have heard one of those): tappa tappa tappa tappa tappa ding! tappa tappa tappa tappa tappa ding! You have to break yourself of the habit of pouncing on the end rhymes and slow down and listen to the musical effects in the middle of the verse.

And you have to learn to read footnotes: Pope is intensely allusive, not only to the classical literature of which most of us today are ignorant, but also to historical events and personages of his day. This is especially true in his satiric poems, which also happen to be his greatest ones. The Dunciad is a magnificent assault on all that Pope happened to think was wrong in the arts and sciences of his day: sloppy writing, craven fawning to and flattery of patrons, catering to the lowest common denominator in taste, and in the sciences especially, an emphasis on specialization without regard to the big picture. That's the point of the middle one of the selections reprinted above.

Like Swift, who satirizes the same thing in Gulliver's Travels, Pope lampooned what he called "virtuosi" -- people who collected butterflies and bred new species of flowers. Pope and Swift's main target was the Royal Society, which they saw (mistakenly for the most part) as a collection of crackpots. The point of the reference to steering "on Wilkins' wings" above, is that John Wilkins, one of the founders of the Royal Society, was fascinated by the possibility of traveling to the moon. We recognize today that specialization is necessary to the advancement of science, and Wilkins may be hailed as a pioneer rather than a lunatic (though in fact he may have been some of the latter) and the Royal Society as a beacon of enlightenment (and the Enlightenment). But Pope feared that scientists would lose sight of the higher aim of understanding God's creation. "The mind, in Metaphysics at a loss, / May wander in a wilderness of Moss" is a reference to specialists in the study of mosses.

And the mind, lost in the footnotes to Pope, may lose sight of the rich sonorities of his verse, the dazzling skill with which he varies the meter of his iambic pentameter couplets. The great conclusion to The Dunciad, in which Dulness triumphs, is as good as anything in Milton, I think. And here, and in some of his Moral Essays, we see why Pope is valuable: He's a defender of good sense, of reason, of truth. Whenever I read him, I always wish he were around to turn his satire on the likes of Sarah Palin and Glenn Beck.